MEDICAL manufacturers were warned decades ago that plastic should not be used to make mesh implants, according to court papers.

The multinationals are accused of ignoring a series of warnings to continue using the plastic mesh in operations that have left hundreds of thousands of women around the world with life-changing injuries.

Campaigners in Scotland yesterday called for the firms, who supplied the NHS with mesh devices, to face criminal investigation.

Around 1800 Scottish women a year were given mesh implants for bladder problems and pelvic organ prolapse in the two decades before its use was suspended in 2014.

But, according to courtroom evidence in America, one of the world’s biggest hernia patch and mesh implant manufacturers, CR Bard and subsidiary Davol were told they should not continue using polypropylene resin in surgical implants as far back as 1997.

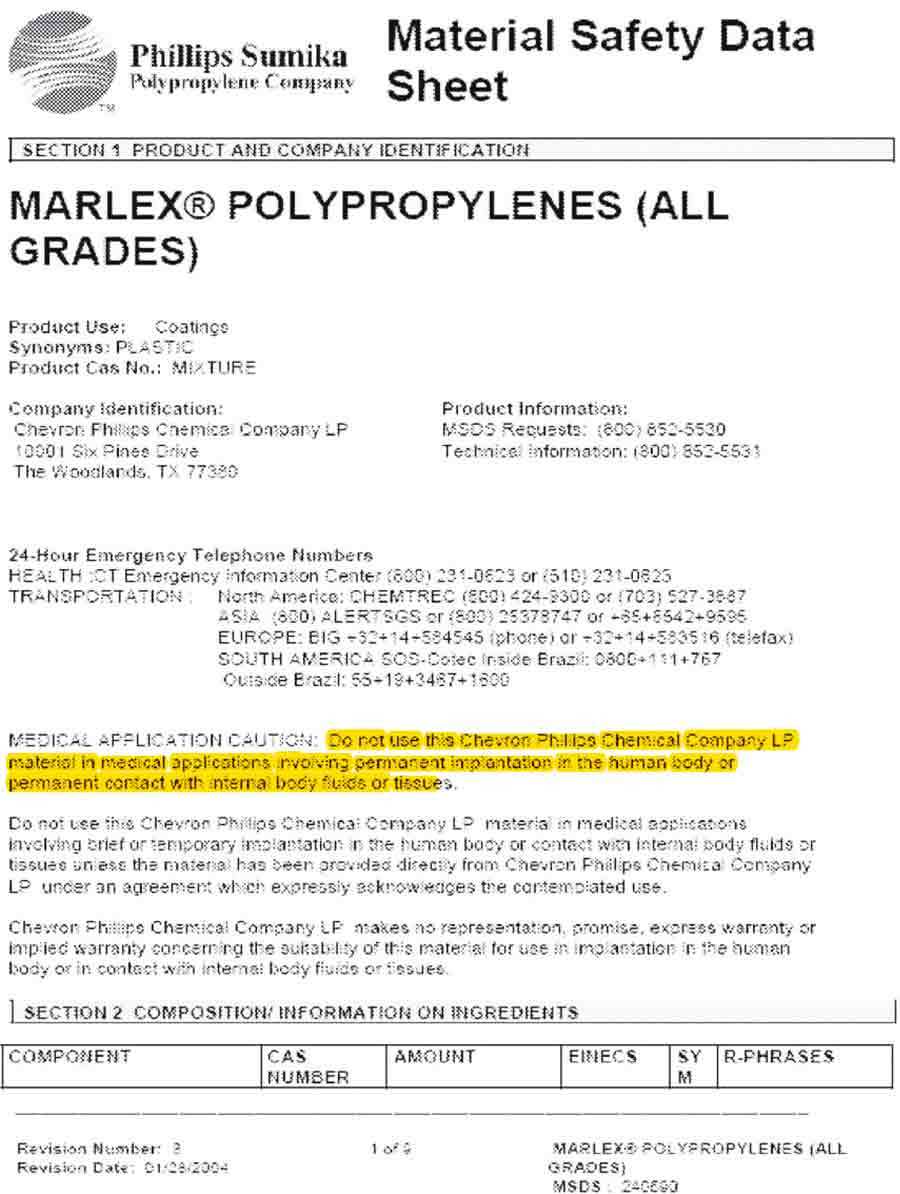

The supplier of the resin called Marlex told them repeatedly that they feared being sued if the product was used in implants.

During evidence in a New Jersey Supreme Court case, former CR Bard vice president Roger Darois admitted receiving a call from Texas-based petro-chemical giant Chevron Phillips, which made Marlex, and told the court: “They were concerned about litigation and the association with the Marlex name with a permanent medical implant.”

Seven years later, in January 2004, Chevron Phillips lodged formal warning notices that Marlex was “not for human implantation” and told medical mesh firms they did not want their custom “at any price”.

But Bard and other mesh manufacturers continued using the polypropylene resin in products, including millions of hernia patches as well as implants for bladder problems and pelvic organ prolapse after identifying alternative suppliers, who, according to memos, were not told it was to be used in medical implants. The NHS in Scotland were among their customers.

Mr Darois admitted at a court hearing in April that Marlex continued to be used in millions of hernia mesh patches as the firm bought the product through third parties.

Fight for justice: “I want to die knowing other mesh victims might now be saved”

One 2004 email from Mr Darois states: “These suppliers will likely not be interested in a medical application due to product liability concerns.

“We purchase our polypropylene monofilament from an extrusion supplier who purchases the resin directly from the resin manufacturers.

“Thus, it is likely that they do not know of our implant application. Please do NOT mention Davol’s name in any discussions with these manufacturers.

“In fact, I would advise purchasing the resign through a third party, not the resin supplier, to avoid a supply issue once the medical application is discovered.”

He told the court: “I was trying to make sure we didn’t have an interruption of supply for the resin we relied on for all those products.”

He said a million of their hernia patches were used every year in the US, and it would have been “irresponsible” to compromise that.

Hernia patients have reported horrific internal injuries, including Michele McDougall, 55, from Edinburgh, who died in May after suffering years of painful internal injury and chronic infections from six mesh patches.

She was too ill for chemotherapy to treat vaginal cancer so rare only three other cases have been recorded.

Another medical manufacturer, Boston Scientific, which allegedly bought counterfeit Marlex plastic from China when suppliers refused to continue dealing with them, says it has complied with regulators.

A spokeswoman said: “While the manufacturer (Chevron Phillips) did create a medical application statement to add to its medical safety data sheet (MSDS) for the resin that we use, and that statement purported to warn against using the resin for certain medical applications, they did so only to avoid potential legal liability because they had not performed medical safety testing.”

The firm claimed Chevron had no “scientific literature” or “testing” to support their 2004 statement, and it continued supplying Boston Scientific until 2011 when it was “unable to procure an additional supply directly from the manufacturer”.

In 2015, a US court awarded Deborah Barba, 51, from Delaware, £75million, most of which was punitive damages, against Boston Scientific.

The award was capped under court rules.

Boston Scientific’s mesh devices Advantage Fit and Pinnacle were regularly supplied and used by 11 health boards in Scotland, including Glasgow, Edinburgh, Tayside, Fife, Lanarkshire and Forth Valley.

Chevron Phillips refused to discuss their warnings due to “matters in litigation”.

Claire Daisley, 48, from Greenock, who has been left crippled by mesh surgery and is now waiting to have both her bladder and bowel removed, joined calls for manufacturers to face criminal prosecution for what victims have called “the biggest medical scandal of modern times”.

Leading mesh lawyer Adam Slater, who gave evidence about mesh to MSPs at Holyrood, said: “There is a concept in the law of criminal recklessness.

“In my opinion, the mesh manufacturers were criminally reckless, and more.

“They knew women would be severely hurt but hid this knowledge so they could profit.”

MSP Neil Findlay said: “Here we have yet more evidence of the outrageous lengths mesh companies will go to maximise their profits all at the expense of lives and well-being.

“What more evidence is needed to take forward a prosecution?”

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe