It was the celebrity friendship of the early 20th Century, two of the world’s most famous people brought together by a shared interest in the afterlife.

One was a passionate believer, the other a debunker.

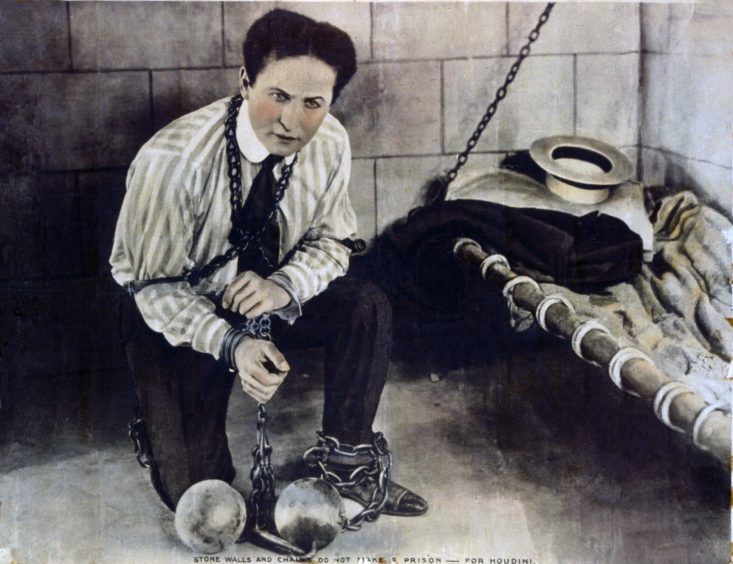

It was 100 years ago that Harry Houdini, while on a UK tour, met Arthur Conan Doyle for the first time, at the author’s East Sussex family home.

Their meeting had been preceded by a flurry of letters back and forth – 10 in two weeks – after Houdini sent a copy of his new book to the Sherlock Holmes creator.

Spiritualism was at the centre of their correspondence. It was also what would eventually tear their relationship apart, very publicly, in the coming years.

A new book about the escapologist, Houdini: The Elusive American, examines the relationship between the men and their conflicting views on mediumship.

“The relationship was all about celebrity for Houdini,” explained Adam Begley, the book’s author.

“He loved being around famous people. He was flattered to think he was friends with the creator of Sherlock Holmes.

“He tried to remain friendly with Conan Doyle for as long as he could, but obviously it was a hell of a balancing act to be friends with the person who is the leading proponent of a religious belief that Houdini was busy trying to knock down.

“Spiritualism was anathema to him. He had a close, bizarre relationship with his mum and when she died he was very upset and tried to reach her through mediums, and failed. When mediums pretended to put him in touch, he could see through their act, because he was a great fooler of people. It offended him to see mediums, including Conan Doyle’s wife, doing such a bad job of fooling people.

“He also recognised it was big business. It was an issue very much in the public eye at the time and being an enemy of spiritualism brought him as much publicity as being an advocate did for Conan Doyle – although the author was not interesting in publicity, because he was famous enough.

“Conan Doyle absolutely believed in what he was saying.”

For some time, Houdini publicly remained on the fence regarding mediums, even after the incident when Lady Conan Doyle claimed to have brought his mum forward to him.

But when the illusionist agreed to join a panel of judges for a competition by Scientific Magazine, which offered a cash prize for whoever could provide proof of psychic manifestations, Conan Doyle felt offended.

A public war of words began between the two men, each of whom would individually embark on popular speaking tours – Houdini explaining why spiritualism was a fraud and the author of The Hound Of The Baskervilles speaking passionately in its defence.

“What turned Houdini against Doyle, as I understand it, was he realised how much publicity there was in attacking mediums,” explained Adam.

“His desire for publicity outstripped his wont for hanging out with a celebrity pal like Conan Doyle.

“What makes it sad for me is Conan Doyle was clearly a nice man who genuinely believed in this stuff and wanted to give Houdini a fair shake.

“Houdini was not a nice man and wanted to basically get the better of Conan Doyle, and he probably would have humiliated Doyle further, or at least tried to, had Houdini lived.

“As it was, Conan Doyle got the last word, and those words remained incredibly generous and perspicacious of Houdini.

“I should be Houdini’s advocate here, but I can’t because the encounter between the pair showed one was a person of character and dignity, and the other wasn’t a lot of the time.

“Houdini was a genius and I certainly agree with him about spiritualism, which I think is nonsense.

“I think Conan Doyle was completely wrong about that. I don’t think you can communicate with the dead, and I think he was fooled by people who weren’t even particularly good at fooling people.

“Houdini, on the other hand, would as soon lie as breathe.”

Richard Pooley, chairman of the Conan Doyle estate and step-great-grandson of the author, last month revealed there were ongoing talks about a film based on the Sherlock creator’s life being made, which would include his relationship with Houdini.

“That will be really interesting – I would definitely go to the cinema to see that,” said Adam.

Houdini: The Elusive American by Adam Begley is available now from Yale University Press.

‘Arthur Conan Doyle still believes in life after death. I know… because he told me’

Ann Treherne was a self-confessed workaholic with an all-consuming job in finance.

From starting as an office junior with the Royal Bank of Scotland, she worked her way up and was in senior management at a building society until, 20 years ago, she gave it all up.

The reason why, she says, wasn’t burnout, or the need for a change of pace. Instead, Ann claims the spirit of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle came to her during a clairvoyance and asked her to set up a spiritualist centre in the Scottish capital.

And, she adds, the Sherlock Holmes creator, who was a high-profile advocate of the afterlife, remains in touch with her today. “I know that sounds fantastical and weird, or that I’m crazy,” she said. “I can understand all those thoughts and I would have had them myself, but I hope by demonstrating I come from a corporate, no-nonsense background, it shows I look at things with objectivity.

“When this all happened, my career trajectory was upwards. I was giving monthly reports to the board and racing around the country visiting branches.”

Ann’s interest in spiritualism began after a series of visions she believed foretold of a major incident.

She felt guilt at not acting on the visions and developed post-traumatic stress disorder.

“I was traumatised and sought out some authoritative people to explain premonitions. I met with Archie Roy, emeritus professor of astronomy at Glasgow University, who was a psychical investigator in his spare time and was president of the Society for Psychical Research.”

Ann set up a circle with like-minded people and it was during these weekly sessions that, she says, the vision of an elderly gentleman came to her.

“I thought it was the grandfather of someone in the group, but he kept coming to me, dripping information by showing me pictures of the surgeons’ hall, a bookshelf and, eventually, Sherlock Holmes,” said Ann.

“It took me a long time to accept it was Arthur Conan Doyle. He instructed me to find a building to set up a spiritualist centre for mind, body and spirit, to be named after him.

“His ultimate aim, I believe, as it was when he was alive, was putting out the message that there is life after death. I think he’s still doing that.”

Ann has just released a book, Arthur and Me, about her life since finding spiritualism.

“Everyone is entitled to their opinion and I don’t try to convince anyone,” she said. “I encourage people to inquire and investigate.

“I always had a healthy investigative mind, but I was brought up in the Church of Scotland – my dad was an elder, my mum the president of the Woman’s Guild, and I went to Sunday school, Bible class and was married there – and mediums were regarded as charlatans and you were accused of dabbling with the devil.

“So, again, I treated it with suspicion.”

Ann added: “Spiritualism generally has a poor perception and I wanted to change its reputation through the Arthur Conan Doyle Centre.

“I wanted to make it approachable for the general public, who generally avoid anything like it, and I think we’ve succeeded through presenting music, arts, room hire, yoga, tai chi and so on.

“I wanted it to be a professional place, not something to be mocked. Since opening, in 2011, it’s been a success.”

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe © Everett/Shutterstock

© Everett/Shutterstock © Uncredited/AP/Shutterstock

© Uncredited/AP/Shutterstock