If money makes the world go round, it is food, food, glorious food that keeps it spinning.

Far from being simply fuel for survival – or a simple, everyday pleasure – what we eat impacts on every aspect of our lives, from politics and the economy to our health and the environment.

From the wealth-building power of salt in the Middle Ages, when the fine crystals were as valuable as gold, to the generations-long dependence on the humble potato, which killed an estimated one million during the Great Famine, it is impossible to over-estimate how our insatiable appetite has shaped history.

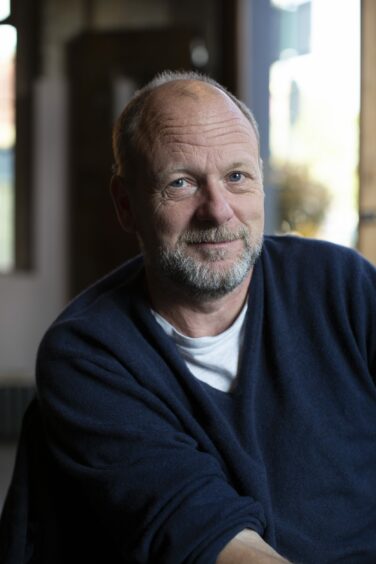

“Food impinges on everything that we worry about from our own finances and health through to bigger issues like climate change, you can’t get away from it,” explained food writer and journalist Alex Renton. “The core of food is pleasure, it’s true, but you can’t talk about food without also talking about politics and economics as well.

“From food banks through to what we’re doing to millions of chickens every year in order to have the cheapest protein on the planet, it’s so important. You can’t really eat and not be political, which means we’re all political.”

The world-shaping power of food is the topic of Renton’s new book, the first official companion to BBC Radio 4’s long-running series, The Food Programme, which has been on air since 1979. Still regularly attracting up to two million listeners per week, the popular show investigates and celebrates all aspects of good food, providing “vital stories for hungry minds”, which Renton admits is the crux of his latest work.

He explained: “That’s exactly the point, isn’t it? Food is an intellectually engaging pursuit on whatever level. If you’re having an argument about whether Burger King is better than McDonald’s and why, it’s almost the same argument as two highly pompous foodies sitting around talking about different types of green tea. In the end, we’re talking about pleasure and joy and happiness. Is there any other thing that we all enjoy as much as food?”

Published this week, 13 Foods That Shape Our World explores how simple produce and ingredients, including spice, oil, dairy, bread and tomatoes, “determine our past, present and future” through power, control, supply and demand and, of course, enjoyment.

What’s more, understanding and exploring our historic connection with food, Renton believes, can tell the full story of our lives – something which he recognised acutely while working for Oxfam on the ground in East Asia.

“I realised in places like Cambodia and Iraq, where I worked in 2003, that if you needed to tell the stories of people who are poor or in trouble, it was a really good idea to ask them what they were eating, what they fed their kids,” explained Renton, who now lives in Edinburgh with his family. “It was much better than simply saying, ‘Just how bad is it?’

“You actually find out an awful lot by asking those questions, and then people back here can relate to that. I also realised that people, even in some of the poorest places in the world, still get enormous joy from foods. It’s a way of bringing families together and communicating, and that’s so universal. All these things are really rich and important, and they come with amazing stories.”

Take bread, the staff of life as it is described in the Bible, for example. The word itself, Renton explains, comes from companion and is a prime example of how human nature – and controlling the masses – is so linked to what’s on our plates.

In ancient Rome, he explains in the book, distributing free grain to the public was essential for keeping peace on the streets, while in 18th and 19th Century London, riots broke out over the cost of bread, quickly leading to political reform. These may be moments from history, but the impact of the price of grain as a result of the war in Ukraine – often described as Europe’s breadbasket – proves that food is always at the heart of world events.

And while food may be, in many ways, more important than money, many of today’s social issues are linked to the fact that produce, in the UK at least, has never been cheaper.

Renton continued: “Today, the average person spends about 9% of their income on food, and a generation ago it was 20% or more. While we obviously have other things to spend our money on now, you have to start to question the food system that delivers food so cheaply, but then doesn’t adequately reward the workers who produce the foods.”

The problems that have arisen, he says, are food insecurity for many, declining health, and the environmental impact on the planet, which can be linked to our desire for affordable food, all year round.

He continued: “Dairy farms are going out of business all the time, and farming is one of the most insecure jobs in the country because we take shortcuts to produce this cheap food with chemicals or cruelty to animals. If people looked at that closely, they might think, actually, it’s just not worth it. We do have the cheapest food in Europe as well. The French and Italians are used to paying a much higher percentage of their income on food, and it seems to work because they have more healthy food economies.”

He added: “They are inescapably intertwined, food and money. Our great grandmother’s would walk into the shops today and be absolutely gobsmacked about what they can see and what’s on offer – and I suspect they might come to think that isn’t all good.”

You say potato. I say a food that has transformed our daily lives

The humble potato is one of the history-shaping foods highlighted by Alex Renton in his book 13 Foods That Shape Our World. Here is an extract:

The humble potato is one of the history-shaping foods highlighted by Alex Renton in his book 13 Foods That Shape Our World. Here is an extract:

From the food of necessity and hardship, the potato is now central to cooking for pleasure, not just as fuel, across the world.

How many words are there for the magical transformations of a potato in the kitchen? A dozen or more come up without having to think: mash, hash, rosti, roast, souffle, boil, croquette, crisp, dice, salad, chip. Not to mention all the potato flour breads, from scones to tortillas, and pommes dauphinoises, where French potato cuisine reaches for the cream-laden divine.

The Irish, with the Spanish, were Europe’s earliest and most enthusiastic adopters of the potato – it once defined their nation as beef did the British or leeks the Welsh. And it is a good bet the Irish have more ways of enjoying potatoes than even the French, who were the first nation to explore the potato in cooking for the wealthy middle classes.

Long before the first French recipes were published in the 1800s, rural Irish people were eating more potatoes than anyone else. With the exception of rice in poorer parts of Asia, no one staple carbohydrate has been so central to a nation’s diet. The chronicler Arthur Young toured Ireland between 1776 and 1778, writing about the economics of the poor – people who generally lived upon “potatoes and sour milk … with, now and then, a herring”.

One family of six, he observed, could eat 252lb (114kg) of potatoes a week. It sounds like a vast amount. But it amounts to just a couple of medium-sized potatoes on each plate at a meal. It was not so poor a diet, either: “The potato is the best single bundle of nutrition there is,” says potato historian John Reader. It could be boring, of course. The addition of those herring made a key difference.

In rural Sweden the same was true: a famous dish of sliced potatoes stewed with pickled young herring or anchovies is called Jansson’s Temptation, possibly after a 19th-Century pastor who easily resisted all pleasures of the flesh except this crusty, pungent dish.

Extracted from The Food Programme: 13 Foods That Shape Our World by Alex Renton, with a foreword by Sheila Dillon (BBC Books, £16.99)

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe