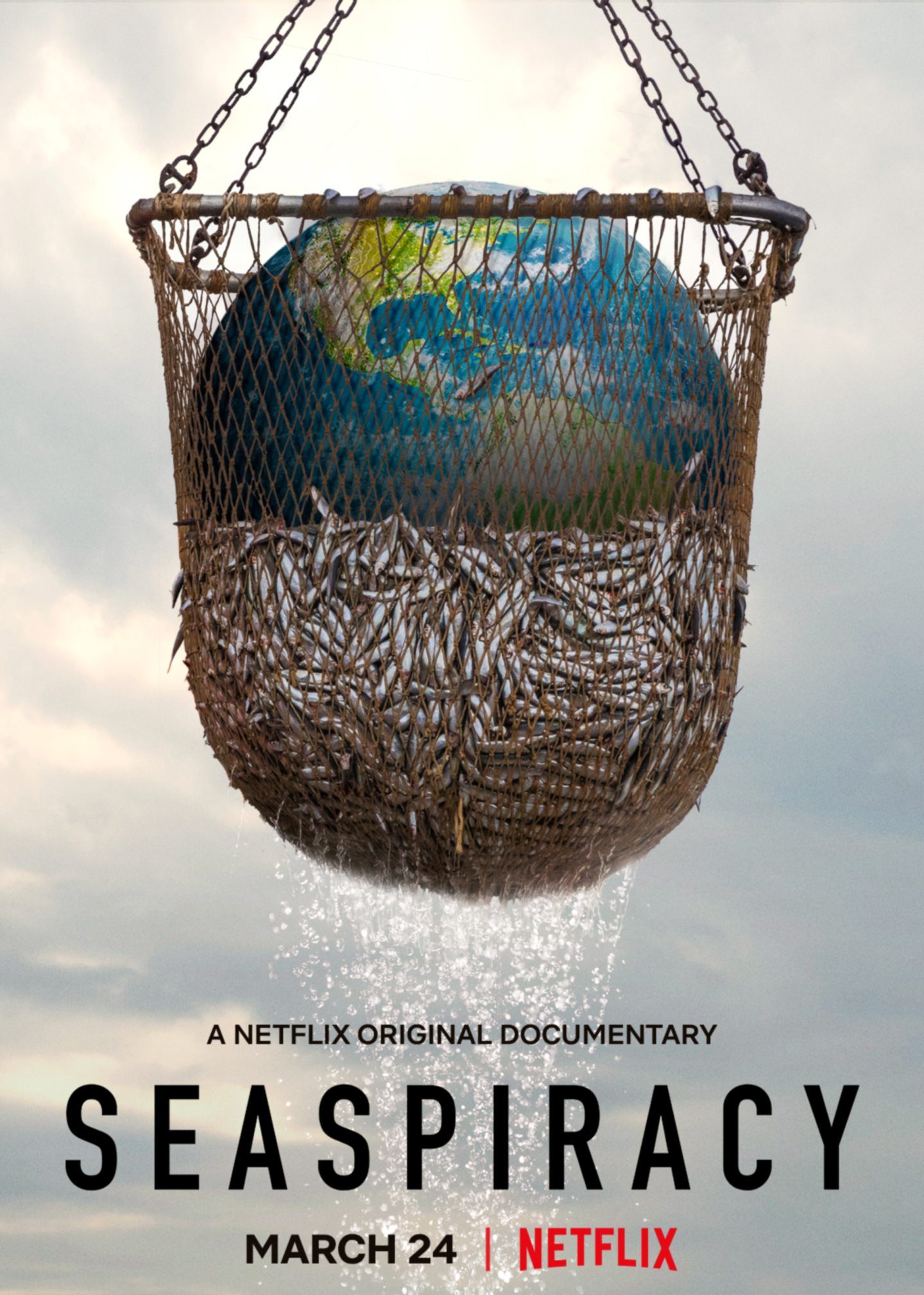

If you’re planning to watch Netflix’s newest shock-factor documentary, Seaspiracy, it would be wise to perhaps keep fish off the menu for dinner that night.

Directed by 27-year-old Ali Tabrizi, the film explores the crisis of overfishing, polluting and damaging of our oceans, which, it claims, with around 90% of the world’s wild big fish now gone, is a huge issue we should all be more aware of as consumers.

Similar to its predecessor, Cowspiracy, which took aim at the pollutive and disastrous ecological effects of the global meat industry and factory farming, Seaspiracy offers up an un-palatable 90 minutes of the negative effects of fish-farming, the prevalence of slavery in Thai fishing fleets and whether human life can survive if we continue with what the UN calls the “continuous increasing trend” of overfishing and potential collapse of our seas.

Although the facts presented in Seaspiracy leave hardly a glimmer of hope, there is one to be found, right here in Scotland: a small, marine conservation organisation on the Isle of Arran showing what can be done with correct management and protection of our seas.

Scotland’s first and only permanent full No Take Zone (NTZ) – areas where all fishing is banned – was established by the Scottish Government in 2008, after years of campaigning by The Community of Arran Seabed Trust (COAST).

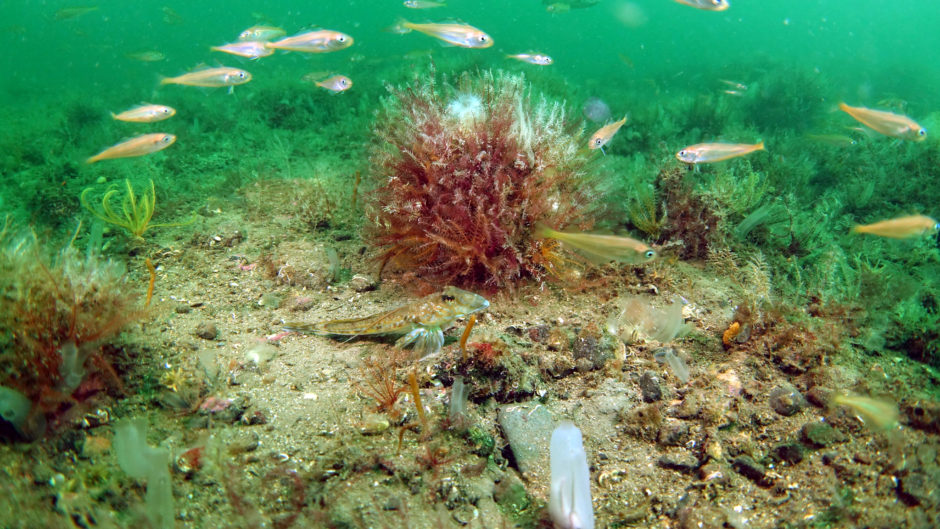

The results have proven that despite over-fishing, trawling and the collapse of reefs, areas can regenerate if given the opportunity to do so.

“A study by the University of York showed numbers of some species have increased by nearly 400% since the community-backed NTZ project was established off the coast of the Isle of Arran,” said Jenny Stark of COAST.

“The NTZ now sits within a 280 sq km Marine Protected Area (MPA) in Lamlash Bay, established in 2014, with fisheries management measures – that promote sustainable fishing – being implemented in 2016, which has shown even more pronounced biodiversity recovery.

“The study also revealed that there are nearly four times more king scallops in the NTZ since research began in 2010, and legal-sized lobster numbers are also four times higher in the NTZ than adjacent areas.

“There is additional evidence of species ‘spill-over’ into surrounding areas, and the study also indicates increasing habitat complexity within the NTZ.”

COAST was created in 1995 by two local scuba divers, Howard Wood and Don MacNeish, who witnessed first-hand the destruction of the Firth of Clyde fisheries, which once had been abundant in herring, cod, turbot and haddock.

Until the 1980s, local communities were able to fish sustainably thanks to long-standing laws that banned practices that towed fishing apparatus along the seabed.

“Growing international demand for seafood and sustained lobbying by powerful commercial fishing interests in the 1980s led the British government to repeal various seabed protection measures,” said Stark.

“Coupled with technological advances in fishing, the new industry-friendly policies opened up the Firth of Clyde to the more destructive fishing practices.

“Fisheries quickly collapsed, and the industry moved on to exploit what little remained of marine resources in the area: scallops and prawns.

“The commercial fishing industry began ploughing through the seabed with scallop dredges, repeatedly passing over the same area to maximize their catch. They damaged the seafloor and maimed coral and kelp forests — vital nursery grounds for fish and shellfish — crippling the habitat necessary for a healthy marine ecosystem.”

In spite of this, the work of COAST has helped restore the area back to good health, and there are no plans currently to open up the NTZ to fishing again.

But what is it like beneath the surface in areas around the rest of Scotland?

“In short, Scotland’s seas are in a dire state,” said Stark.

“Native oyster reefs around Scotland are now completely extinct and whitefish and herring stocks have crashed to commercial extinction.

“According to the Scottish Marine Assessment 2020, 11 ‘key’ fish stocks were assessed in 2018 – of these, five (46%) are overfished.

“In every region studied, losses of biogenic reef were reported.

“Argyll lost 53% of its flame shell reefs, the Clyde lost 9%, as well as 10% of its maerl beds in the past decade.

“The Outer Hebrides lost 27% of their seagrass and 58 hectares of serpulid reefs have gone (about 50% of their total range).

“There are a huge range of pressures on our seas – climate change, pollution, overfishing – but one of the fundamental problems is chronic and persistent damage to the seabed.”

Callum Roberts, a marine conservationist at the University of Exeter has equated scallop dredging to “cutting down a rainforest to catch a parrot.”

Roberts is also featured in Seaspiracy, and the film claims that bottom trawlers wipe out 3.9 billion acres of the seabed per year, and that an area the same size as 15 countries including huge masses like Australia, Greenland and Mexico has already been destroyed.

The film also makes the claim that at the rate fishing is currently happening, our seas will essentially be empty by 2048.

Yet this claim and others presented have been criticised by some marine biologists who have said the documentary is a simplistic portrayal of a complex industry and poses a misrepresentation of facts.

Professor Paul G Fernandes , Chair in Fisheries Science at the University of Aberdeen is one of them.

He said: “[Seaspiracy] expresses some valid concerns in relation to fisheries in developing countries, shark finning, and human rights abuses; but it is way off the mark in its evaluation of the activity in developed countries where drastic improvements have been made in the 21st century.

“Not acknowledging the huge efforts that have gone into making fishing sustainable in the north Atlantic and north Pacific is disingenuous at best, if not downright devious.”

But despite some scientific pushback of the topics explored in Seaspiracy, the restorative work of COAST isn’t easy to argue with.

The group has played a pivotal role, working with Fauna and Flora International, in helping set up the Coastal Communities Network. To date this network has assisted another 15 community groups around the coast of Scotland to improve the protection of their own local waters.

Local MSP, Kenneth Gibson said: “The community on Arran should be very proud of their achievements over the last decade to promote marine conservation.

“This study proves the potential of effective marine management and I will be pressing the Scottish Government to seriously consider the creation of more NTZs as part of their marine management plans.”

The work on Arran has also been recognised with a series of environmental awards, has influenced national marine protection policy, and has highlighted the importance of community involvement in marine protection projects.

“Arran’s conservation success has been recognised internationally and is inspiring greater involvement of local communities around the UK and further afield,” said Dr Bryce Stewart from York University’s Department of Environment and Geography.

“Local communities around the UK have looked at the story unfolding in Lamlash Bay and – like COAST – have now decided to take the destiny of their coastal waters into their own hands.”

Seaspiracy, streaming now, Netflix

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe © Ali Tabrizi/Seaspiracy

© Ali Tabrizi/Seaspiracy © COAST Outreach

© COAST Outreach