Shoppers buying products containing natural rubber should question where it comes from as firms attempt to conceal the environmental damage inflicted by plantations, researchers warn.

The Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh (RBGE) has joined with the Chinese Kunming Institute of Botany to warn commercial rubber farms could cause the same levels of ecological damage and deforestation as oil palm plantations.

The organisations are working together on groundbreaking research that will slow the level of biodiversity damage in areas worst affected by the crisis, mostly south-east Asia, gathering data that will empower authorities to support small farmers who have staked their livelihoods on the success of rubber tree plantations.

Dr Antje Ahrends leads a team that is researching rubber and associated deforestation at RBGE. She explained where consumers are most likely to find natural rubber in products, and why shoppers should be wary of brands trying to “greenwash” products.

She said: “The vast majority of natural rubber is used in the production of tyres, thus there is a direct link to transport. It is also used in various other products, like PPE, boots, gloves, hoses, insulation, yoga mats, mattresses and condoms.

“At present, it is difficult to impossible for consumers to distinguish genuinely environmentally sustainable and socially responsible products from those that claim to be but are not.

“Public awareness around the problems caused by rubber is low. This is because a lot of companies use the mere fact that natural rubber is produced from trees to claim that this is an environmentally sustainable and carbon neutral product.”

However, Ahrends said an awareness campaign had helped consumers understand the damage done by oil palm plantations to tropical forests and a similar exercise was needed when it comes to rubber.

“People are aware that the practice endangers the life of mammals they love like orangutans and that it destroys peatland forests, which goes hand in hand with huge amounts of carbon emissions. That hasn’t happened with rubber yet but when the public is aware of a problem it becomes circular, and now there is huge pressure on companies to use deforestation- free palm oil, or no palm oil at all.”

Ahrends points out that natural rubber has the potential to be a great renewable resource but that it can also put the biodiversity of vital forests and the incomes of small farmers at risk.

She explained: “While it is true that rubber is a renewable source and that the carbon footprint of natural rubber is lower than that of synthetic rubber, a lot of the natural rubber production has also led to deforestation and to net carbon emissions and biodiversity loss. In countries such as Cambodia and Laos it may also have led to land grabbing by larger companies.”

Ahrends urges consumers to push companies harder on where they source their materials. She said: “Some companies have signed up to a declaration that they are only going to buy natural rubber from sellers who are certified by the Forest Stewardship Council, but only around 4% of the global rubber production is currently certified.

“I would always be tempted to email a company and say, ‘are you sure this is deforestation-free rubber? Has it been responsibly sourced? Or is there a risk that it comes from a major company in Cambodia that has just disowned lots of farmers and planted rubber plantations in a national park?”

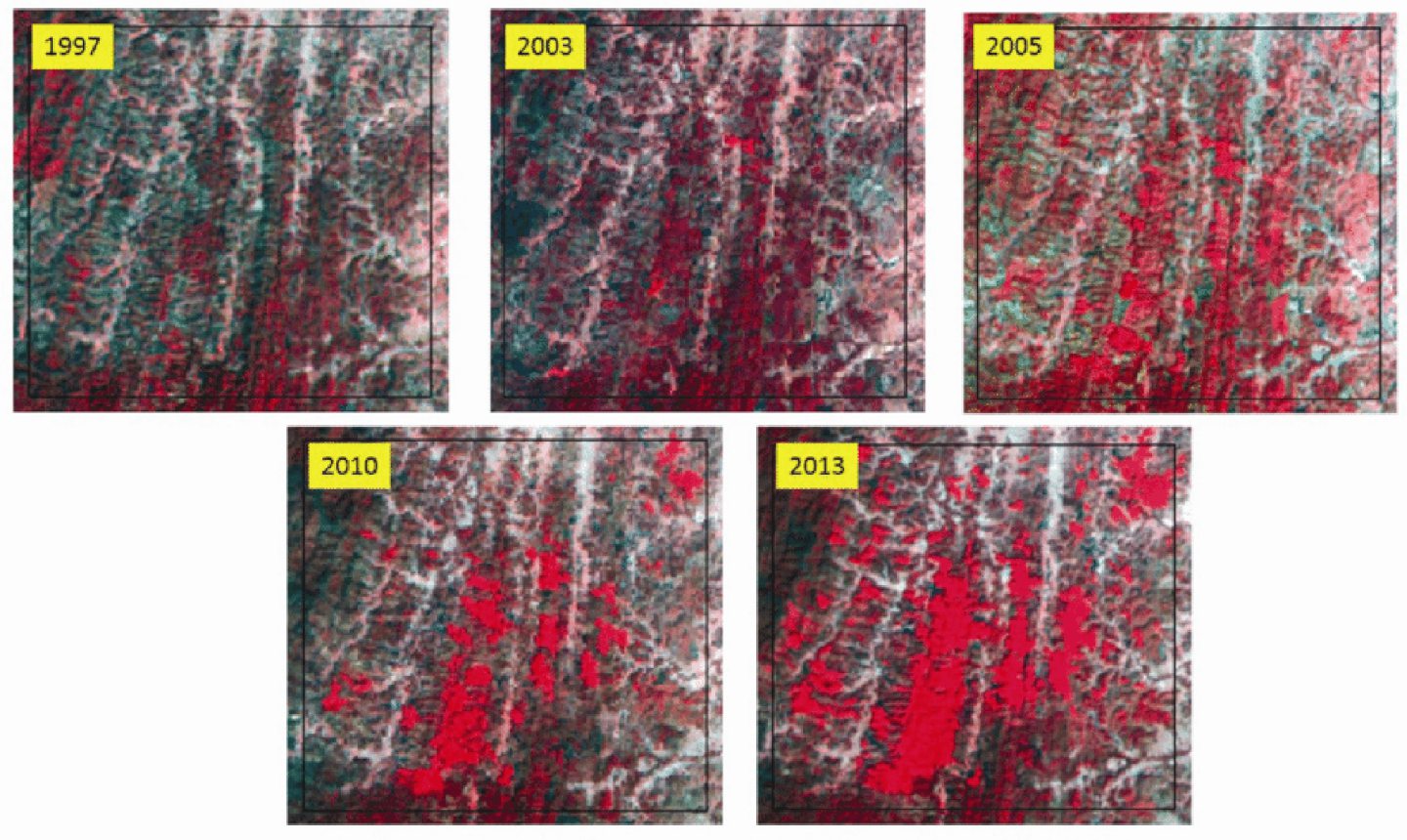

Through the UK Global Challenges Research Fund, Dr Yunxia Wang joined Ahrends’ team at RBGE from Leeds University in May and is leading the technical research arm of the project. Her groundbreaking work tracks rubber plantations and associated deforestation, showing a tight correlation between the price of rubber and the loss of forests.

The data she collects will help decision-makers know where the worst deforestation is happening, and help assess what land is suitable for rubber tree plantations, and which is not. Wang said: “I am mainly in charge of the technical aspect of the project. There has been previous projects that have looked at this on a smaller, local level, but with this project we wanted to know the much larger spatial scale of rubber plantations for the whole of south-east Asia.

“We use imagery from the space satellite Sentinel-2 to track the rubber and pick up new, smaller plantations for small farmers.”

While Ahrends explained that she is happy the public is more aware of the need for sustainable products, she also expressed her hope that concerns continue to grow and encompassed the ecological and ethical problems that come with sourcing “eco-friendly” goods: “Just because it comes from a tree doesn’t necessarily mean it is a good thing. That tree might have replaced a natural biodiverse forest.”

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe © SYSTEM

© SYSTEM