So he has done it. Not satisfied with putting extraordinary pressure on Ukraine and exposing Nato’s limits, Vladimir Putin wanted more.

Before the slow progress to his invasion is forgotten in the hurtling pace of war, it is worth noting American and British intelligence was right about Putin’s plans and almost certainly right about the Kremlin already having a list of names to fill a puppet Ukraine government and of the opponents to be eliminated first.

A lackey regime might then copy Crimea in 2014 and hold a referendum on the country joining Russia. While ignoring laws and conventions, Putin still likes the pretence of due process.

Before that, Russian forces are likely to continue to destroy key Ukrainian military infrastructure and install some of their own, possibly including missile systems. Already Belarus has offered to accept them, and installations in Ukraine would soothe Putin’s constant complaint that Nato has installed their own missiles on, as he describes it, Russia’s porch.

The unfolding refugee crisis? Well, thousands, even millions of Ukrainians flooding to European Union and Nato countries, four of which share a border with Ukraine, would be a double-win for the Kremlin: destabilisation of those countries and removal of people likely to resist Russian presence.

The Ukrainian government has called for armed resistance. It’s hard to tell how extensive this will be, but some will undoubtedly resist and the country has a history of partisan warfare, including against the Soviets, even in a small-scale, for years after the Second World War.

In addition to a “kill list”, we can expect Russian punishment and retribution. Putin’s language of Ukrainian “fascists” and the need for “de-Nazification” (in a democratic country with an elected president of Jewish origin) provides a laughable but ghastly pretext. Putin is unlikely to make new demands of Nato; there is no need. His position is that the West turned Russia into an enemy and he is turning back the historical clock. In his attempts to do so, Putin has shown total disregard not just for international law and norms, but for the international economic system. It was a fallacy that the West’s threat of unprecedented sanctions would deter Russia. They will do nothing now to slow the action now it has begun.

The Russian president will be content to run a semi-self-reliant regional economic system. Semi-self-reliant because his regional plan reintegrates vast amounts of territory, industrial plant, natural resources and, alas, people. Semi-self-reliant also because of his marriage of inconvenience with China. An unequal partnership not in Russia’s favour, that nevertheless furnishes Moscow some political support.

Sunday Post Analysis: A paradox and now a pariah but Putin may just have made his greatest mistake

Most importantly, China remains a vast economic market, to which Russian oil, gas and coal have been sold below market price. Putin does not want to develop a domestic Russian economy, needing global economic integration. Despite its energy resources, Russia’s per capita GDP is only ahead of those of Chile, Panama and Equatorial Guinea.

However, even as we see fighting across Ukraine, a subtler but just as disarming aspect of recent developments is Putin’s work parallel to Ukraine. He has deepened his control over neighbouring states. To that, add the absolute obsequiousness of Belarus’s Alexander Lukashenko. Converting his country into a staging post for Russian attacks on Ukraine’s capital was insufficient – Lukashenko pleaded during a television interview that Putin should promote him to colonel in the Russian armed forces. We still do not know exactly what those forces did in Kazakhstan in January, but a supposed coup was ended against a leadership in a country that Moscow considered to be politically friendly, and a core of its Eurasian Economic Union.

Putin does not care about Western opinion, let alone Western economic resources, and cares less about losing relationships with the West. He cares only about correcting what he believes is a distorted version of history, and the maintenance, for now, of a coterie of regional supplicants.

What risks harming Putin most is historical posterity. Historical analogies are dangerous. Supposed parallels are rarely exact but does Putin see himself as a Catherine the Great, expanding the Russian empire northwest and south to the Black Sea? He clearly sees himself as the great defender of subjugated Russians but his historical narrative is, objectively, horrendously false.

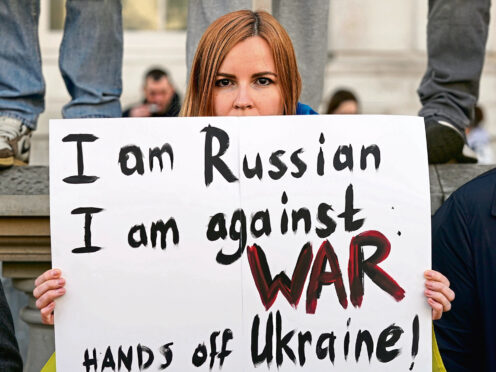

Many Russians know this of course and, despite domestic pressure, alternative narratives continue to be heard. Anti-war protests in Russia are small, and curtailed by police, but still significant. Justifying war remains a hard sell. More casualties, Ukrainian and Russian, will harm his standing. Major wars initiated by Imperial Russia and the Soviet Union have brought domestic earthquakes and already Ukraine is being compared to Afghanistan.

Putin can play historical saviour now, but that will not endure. We routinely refer to Putin’s formative experiences in East Germany in 1989, as a junior KGB operative in Dresden. There he frantically burned secret documents while a peaceful democratic revolution swept away communist control and ultimately the 350,000 Soviet combat troops stationed there.

He knows from experience that statues can be erected but when historical records are corrected, they come tumbling down. Little solace now, not least to beleaguered, fearful Ukrainians and to all of us but, long-term, Putin cannot win.

Professor Rick Fawn is a specialist on international security and an expert on communist regimes

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe