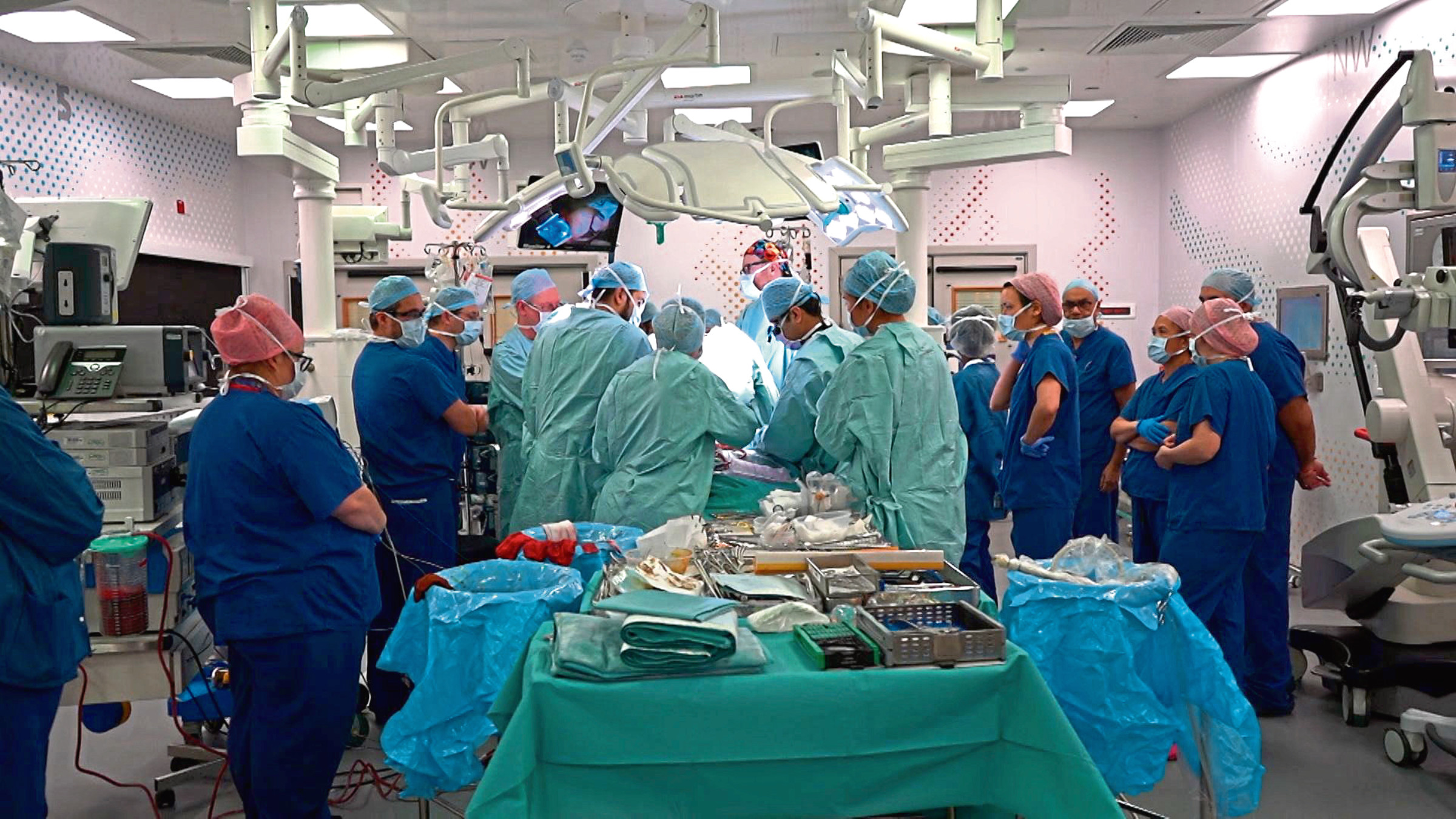

The landmark series of operations to separate the conjoined twins took 55 hours, involved more than 100 medical staff and made headlines around the world.

Now the surgeon who rebuilt Safa and Marwa Ullah’s heads has revealed it was the most challenging work of his career.

Professor David Dunaway led the team which carried out the intricate series of operations on the two-year-old twins at Great Ormond Street Hospital.

The girls were finally separated in February, following surgery which took five months to complete.

The London team can boast world-leading expertise in separating conjoined twins, while Professor Dunaway has carried out a series of landmark operations to rebuild children’s faces in Africa as well as the UK.

But, speaking at his home near Glasgow, after the BBC revealed the twins’ operations, the acclaimed surgeon told how his medical career very nearly stalled before it had started.

He said: “I failed my first year medical exams at University College and dropped out. I didn’t really put the work in,” he explained.

“My dad insisted I get a job and I ended up working for the battery company Ever Ready.”

It was while sitting at a workbench in the London factory that he wondered what he was doing with his life, when former colleagues were qualifying as doctors.

“UCL let me back in to study dentistry and I went from there back to medicine,” he recalled. “It’s a good lesson in how, if you persevere, you can get things back on track.”

He graduated in dentistry in 1980 and then medicine at Manchester University in 1989 before launching his career in theatre.

Professor Dunaway, 63, regularly works 15-hour days. His wife, Sue, said: “He never takes time off.

“When we are on holiday he is always checking emails, Skyping colleagues in other parts of the world or planning his next surgery.

“I am hoping he will retire in three years or so.”

The look on Professor Dunaway’s face, however, suggests she may have to wait a little longer.

The couple met when he was a dental student and she was a nurse at North Stafford Hospital in Stoke-on-Trent. She gave up her job to raise their three children but they still work together as volunteers in the Swedish-owned Nordic Medical Centre in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.

“Our patients include children whose faces have become gangrenous by infection and poverty in sub-Saharan Africa,” she said.

It’s a world away from Professor Dunaway’s previous job at Canniesburn Hospital, the former west of Scotland plastic surgery unit, where he often had to save the lives of patients left with horrific injuries following late-night, city-centre fights or car crashes.

Life on the frontline of healthcare in Glasgow was a stepping stone to his current role developing a UK expert centre to handle the most complex head and face surgery. “Our first separation of UK conjoined twins was overseen by an American colleague who flew in to teach the team,” he said.

Conjoining happens when identical twins, who begin life as one fertilised egg, fail to separate fully in the womb.

Professor Dunaway is now a world-renowned expert in separating twins joined at the head, the rarest type, which only happens in one in ever 2.5 million births.

The success rate is 50%. To date, his team has separated three successfully.

Looking back on his career, Professor Dunaway revealed that his happiest moments were successfully separating conjoined twins.

“It is hugely rewarding to give them the chance to live independently,” he said.

Great Ormond Street separates one set of conjoined twins every year.

The last operations on Safa and Marwa took place in February, when they were aged two. The surgeons now hope the twins will be able to walk before their third birthday.

The two girls were released from the hospital a few weeks ago but remain in London with their mother Zainab and their grandfather Mohammad.

Their father died of a heart attack two months before they were born, leaving Zainab with nine children.

“Her extended family have been hugely supportive,” added Professor Dunaway.

The successful operations to separate the girls represented a triumph of surgeons’ skill and advanced technology.

They used virtual reality to create an explorable model of the twins’ skulls.

This enabled surgeons to visualise the complex structure of their heads as well as the positioning of their brains and blood vessels.

Doctors first worked to separate the girls’ blood vessels and then inserted a piece of plastic into their heads to keep the brains and blood vessels apart.

Scans had shown that the girls had two distinct brains but these were misshapen, which the plastic and an accompanying pulley system helped to correct. The final major operation involved medics building new skulls using the girls’ own bone.

The operation: How surgeons used virtual reality to rebuild conjoined girls’ skulls

The successful operations to separate conjoined twins Safa and Marwa Ullah was a triumph of surgeons’ skill and advanced technology.

Surgeons used virtual reality to create an explorable model of the girls’ skulls to guide them during the arduous operations.

This enabled them to visualise the complex structure of their skulls as well as the positioning of their brains and blood vessels.

The team also used 3D printing to create plastic models of the skulls to be practised on.

Cutting guides were created so surgeons could work more precisely.

Doctors first worked to separate the girls’ blood vessels and then inserted a sheet of plastic into their heads to keep the brains and blood vessels apart. Scans had shown that the girls had two distinct brains but these were misshapen, which the plastic and an accompanying pulley system helped to correct.

The final major operation, when the twins were two, involved medics building new skulls using the girls’ own bone.

They also used tissue expanders to ensure each girl’s skin would stretch over the top of her head.

The bill to separate Safa and Marwa, who were born in Peshawar in January 2017, came to around £1 million and was paid for by a Pakistani businessman.

“Ideally, we would have separated them a year earlier, had the money become available,” said Professor Dunaway.

“We have to be careful not to be seen to spend NHS money.

“The best time to carry out the surgery is at a year old.”

More miracles: Life-changing ops that made surgical history

Here, David Dunaway looks back on three notable operations during his illustrious career in theatre.

The twins

Sisters Rital and Ritag Gaboura were born joined at the head in 2010. Parents Abdelmajeed, 31, and Enas, 27, both doctors from Sudan, knew their only hope of survival lay in separation at Great Ormond Street. And theirs would be only the second such operation performed at the London hospital.

Ritag’s high blood pressure and failing heart were putting her in danger.

“Her heart was having to pump for both twins and she was underweight,” said professor Dunaway.

The sisters were separated in three operations of 10 hours or more.

The girl

Isobel Flintoff, now 14, from Yorkshire, was born with Pfeiffer syndrome, which causes the premature fusion of facial bones.

When she was just three months old, Professor Dunaway and his team operated to make her head bigger, increased the size of her eye sockets and brought her face forward to improve her breathing.

Professor Dunaway said: “Even as a young infant, she was very charming and a great character.

“I have a great fondness for Isobel – she calls me Dave now. She’s had a lot of tough times. But she keeps coming out of them and doing better.”

The boy

Professor Dunaway rebuilt the face of a Bosnian boy who had been born with a disfiguring condition.

Stefan Savic had a Tessier facial cleft which left him with a two-inch wide hole in his head, a poorly formed nose and a lump between his eyes.

He was spotted in 2004 at the age of four by a British soldier stationed in Bosnia, Staff Sergeant Wayne Ingram.

Following a 10-year fundraising campaign, Stefan, now 19, was taken to Great Ormond Street for surgery which was finally completed in 2014.

Professor Dunaway said: “It gives me great joy to help children recover from a very disabling condition such as Stefan’s.

“We could never create what most people would call a perfect result but we can help the child reach for what most people would call normal.”

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe