“I’m a survivor,” says David, as he sways to the strains of a Scottish air drifting on the summer breeze. “I’ve been surviving all my life.”

The self-declared pagan is sitting in the Growchapel Community Allotment Gardens on their first open day. His bucket hat chimes with the festival vibes of the impromptu ceilidh band but the tired eyes peering out from under it betray a vulnerability at odds with the bravado.

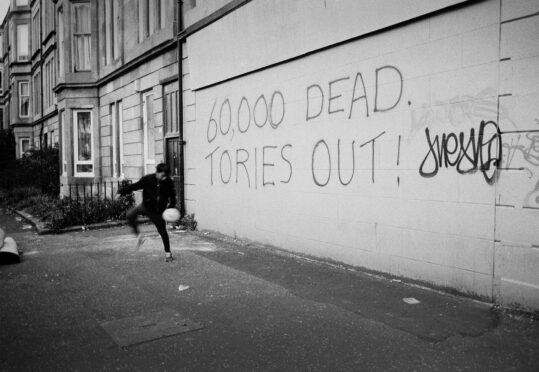

The allotment gardens have sprouted like cress from a patch of derelict land in Drumchapel, one of Glasgow’s sprawling estates. If you want to see how deprivation translates into disease and lives cut short, Drumchapel is an ideal place to go: a community where, in the 21st Century, death typically strikes men well short of the “threescore years and 10” benchmark of the Old Testament.

One of four large peripheral estates built in the post-war years to house those displaced during the slum clearances, it was supposed to be a haven but it lacked amenities, transport and community cohesion. Billy Connolly, called it a “desert wi’ windaes”. Today, it offers a particularly frightening window on the very real challenge of surviving in so much of poorer Scotland.

Broke Scotland: Next FM urged to save lives cut short in poorest streets

Nonetheless, the allotment truly is a small green haven, sandwiched between two streets of low-rise houses, and flanked at either end by multi-storeys. Like many of those who come here, David, 53, suffers from anxiety, which is intricately and increasingly bound up with his economic and physical condition.

For decades he developed strategies to deal with that anxiety, working nights as a security guard to avoid having to socialise and heading out into the hills at weekends.

“When an alarm went off, I’d be sent to check for burglars or a fire,” he says. “It could be dangerous but it kept me busy.” In 2017, however, those strategies were ripped from him. One day he fell and broke his hip; arthritis took hold and he became housebound. He was still on the waiting list for a hip replacement when Covid struck.

David’s mother died years ago from cancer at the age of 57, his father soon after “of a broken heart”. He lives alone and spent most of lockdown playing his favourite computer game. “I didn’t have to shield but I couldn’t go to the supermarket and stand in a queue and then get myself home again,” he says. “I was so isolated I forgot how to interact with people.”

Though he finally got his new hip last year, David has never seen a physiotherapist. His left leg is an inch and a half shorter than his right and he is in constant pain. To make matters worse, on his last day in hospital after his hip operation, he collapsed with a seizure and was diagnosed with epilepsy.

“I used to be super-fit, which makes the loss of mobility harder to bear,” he says. “Today, it was an ordeal just to walk the half-mile from the shopping centre to the garden.”

All his working life, David prided himself on staying “off-grid”. “I never claimed anything and I wasn’t on any government list,” he says. Now he receives benefits and has to report to the Jobcentre under threat of sanction. With the price of food rising, he often goes hungry. “I only eat one meal a day and at least one day a week that meal will be cereal,” he says.

Going to the allotment helps keep despair at bay. The plot he uses belongs to so-called community links practitioners at Drumchapel Health Centre, all-purpose fixers who lighten GPs’ loads by tackling the social issues affecting their patients’ health.

They run a weekly group here. For David, it’s not the same as being out on the hills but it lifts his mood. “I like getting my hands dirty,” he says. The plot has yielded potatoes and a box of herbs. Earlier that day, someone spotted the first strawberries: red, but not yet ripe.

It’s 3pm. The musicians – two fiddlers and an accordionist – are packing up their instruments. “Let’s go and join the others,” I say. “I think they are planning to replant the sunflowers.”

“Yes, let’s,” he replies. “We could all do with sunflowers in our lives.”

In 2022, the experts at the Glasgow Centre for Population Health (GCPH) accompanied a chunky new report interrogating some worrying trends in Scottish and wider UK life expectancy with a short animation summing up the big picture. Since the 1800s, it said, the figures had gone up and up, stalling only briefly, in times of crisis, such as the two world wars and the Spanish flu pandemic of 1918-20. But in 2012 longevity plateaued in the UK while continuing to extend in other countries.

The flatlining chart was depressing enough but it masked an even bleaker reality. A close analysis of the seeming stasis revealed life expectancy in the most affluent areas was continuing to rise, albeit at a slower rate than before, while in the most deprived areas it was actually falling outright. In the poorer communities people are being “swept up”, the GCPH warned, “by a rising tide of poverty. They’re dragged under by decreased income, poor housing, poor nutrition, poor health and social isolation.” And all of this had recently translated into far higher Covid infection and death rates in communities where people could not afford to shield.

Nowhere are the maladies more visible than within Glasgow itself. A post-industrial city, whose once-thrumming shipyards long ago fell into decline, it is pockmarked with areas of multiple deprivation where money is short, multiple overlaying illnesses – or comorbidities – are rife and the future is bleak.

The same could be said of other post-industrial cities, of course. But Glasgow has excess levels of mortality and poor health even after its economic problems are taken into account. In other words, its population is less healthy than the populations of Liverpool or Manchester, which also suffered the loss of their heavy industries.

This so-called Glasgow effect is visible in almost every set of health statistics, not least life expectancy. According to the National Records of Scotland, across Glasgow as a whole between 2018 and 2020, the figures stood at 78 years for women and 73 years for men: that is, respectively, four-and-a-half and six years less than the UK national average.

As for healthy life expectancy – defined as the number of years in which people feel themselves to be living in good health – for men in Glasgow city, the Office for National Statistics (ONS) reported it to stand at 55 years in the run-up to the pandemic.

This was not only eight years below the UK average but also significantly lower than the figures for Manchester (58) and Liverpool (59). Across the whole of the British mainland, the only local authority to fare marginally worse on this particular metric was the washed-up coastal economy of Blackpool.

The relative position of Glaswegian women was not much better with their healthy-life expectancy of 58 years against a UK average of 63 – and for Scottish women as a whole, this measure, which has merely stagnated in the rest of the UK, has recently been in freefall.

Even within the context of an increasingly sickly Scotland in which it looms so large, Glasgow still stubbornly stands out. Across the city, one in four men will die before his 65th birthday.

You need to drill deeper again and explore the disparities within the city to find the most chilling variations of all. In 2021 a GCPH report, Health in a Changing City, found that in 2017-19, the men in the most deprived 10% of Glasgow zones could expect to die 15 years earlier than in its wealthiest communities, a gap that had widened from 12 years in 2000-02.

For women, the same gap rose from 9 to 12 years over the same period. Getting still more specific, and looking at named individual neighbourhoods, the report revealed a 18-year gap between the highest male life expectancy in Pollokshields West (83 years) and the lowest in Greater Govan (65).

As for Drumchapel, it ranks third from the bottom on this morbid league table of male deaths, with lives only two years longer than in Govan. Amid its tower blocks and modern tenements, conditions have often been little better than in the old slums the original residents left behind. With houses built not of brick but of porous Wilson block, damp spreads.

“We had the highest level of child asthma on earth,” David, who moved to Drumchapel in the 1980s, told me. “I remember the dysentery outbreak in the early ’90s, too, with sewage flowing down the street.”

What throws Drumchapel’s disadvantage into sharper relief is its proximity to prosperous Bearsden. Just a few hundred feet separate the two yet moving from one to the other is like swapping Kansas for Oz.

A walk along Drumchapel’s main shopping street is a grim pilgrimage past betting shops, pharmacies, a solicitor’s office, a vaping shop, a One O One convenience store (with off-licence), a Jobcentre and a range of takeaways selling pizzas, chips and kebabs.

Middle-aged men in jackets and caps, their faces hardened by poverty, smoke in the rain outside the Butty Bar. Young men in tracksuits smoke in the rain outside Greggs.

At the tree-studded junction of Roman Road and Drymen Road in Bearsden, by contrast, I count no fewer than seven cafes and restaurants, all with pretty names like Grace & Favour.

They nestle in beside a florist’s, a craft butcher’s, a Paul Smith clothes shop and an estate agent’s advertising at least one property close to £1 million.

Even Bearsden’s takeaways are luxurious. The Scallop’s Tale sells moules marinière at £16.95; Dining In With Mother India, king prawn curry for £24.99 per kg. Way back in 1995, when Glasgow’s deindustrialisation was already well advanced, in the wake of a BBC documentary, the then shadow secretary for social security Donald Dewar, whose constituency included Drumchapel, told the House of Commons: “Most Members of Parliament recognise the link between deprivation and health…Between 1981 and 1991, male mortality between the ages of 15 and 46 rose by 9% in Drumchapel; in Bearsden, it fell by 14%…

“Young men in Drumchapel are twice as likely to die as those living in an affluent and leafy suburb. They are 75% more at risk during major surgery. This may not be a pleasant subject, but it is a fact that for a person living in a poor area such as Drumchapel who requires a bowel operation, the chances of developing complications and dying are 50% higher than those of a person living in the neighbouring affluent area.”

All true, but a generation on we might have hoped to have made some progress in closing this chasm. Instead, the statistics suggest, we are doing precisely the reverse.

The Sunday Post view: It is beyond time to end obscenity of early deaths on our poorest streets

Deep End

Before meeting David at the allotment, I spend a morning shadowing Lorna Robertson, one of those links practitioners at Drumchapel Health Centre, a few hours that demonstrate all too clearly the myriad ways poverty has of getting under the skin.

All the GP surgeries at the health centre are “Deep End” practices – the term used for the 100 practices serving the most deprived areas in Scotland, whose expertise is pooled in the hope of tackling health inequalities through the Deep End Project at Glasgow University. Eighty-six of those 100 practices are in Glasgow.

One of the biggest challenges of such practices is the “inverse care law”: the principle that there is an inverse relationship between the availability of healthcare and the populations that most require it. Patients who attend Deep End practices tend to be suffering from a combination of conditions: diabetes, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD – that is, lung disease, which doctors overwhelmingly blame on smoking), asthma, high blood pressure, heart problems and strokes, along with depression and addiction.

These are not problems that can be easily dealt with in a 10-minute GP appointment and links practitioners were created out of a desire to address this shortcoming in the system. Today, there are more than 70 of them based in Deep End practices in Glasgow, helping patients access benefits, dealing with housing associations and connecting with third-sector organisations that run the likes of bereavement counselling or recovery cafes.

On the morning I spend with Robertson, her patients include Christine, a 45-year-old wheelchair user born with cerebral palsy, and Michael, not his real name, who suffers from long-term mental health issues.

Christine had always coped well with her condition, living independently with little outside support but a recent cancer diagnosis knocked her for six. She is struggling to perform tasks she once took for granted and is distressed about the loss of her hair. Robertson contacts the social work department to chase up a homecare referral and scours the internet for a pre-tied bandana which Christine will be able to pull on and off with ease. Transport is also an issue for patients like Christine.

“The health system is designed by – and geared towards – people with cars,” says Robertson. “Those without cars may be taking three buses to get to an appointment one day and another three to get to an appointment the next. That adds to the financial pressure and the stress.” And, of course, where the result of this lack of access is missed appointments, it can easily translate into treatments being missed, with dangerous consequences.

In her five years in that role, Robertson says her caseload has grown: a result of welfare “reforms”, the pandemic and now the cost of living crisis. Everyone is scared of what will happen as energy prices soar. “There is already so much pressure on support services,” says Robertson. “We try to plug the holes but the water keeps coming.”

In-work poverty

A life of poverty is a life spent firefighting. If you are well off, you are more likely to invest in your own wellbeing. You are more likely to eat good food, get fresh air and go to the gym.

You will probably remember to make an appointment for cervical smears and breast screenings; and then you’ll remember to attend those appointments.

But everyone’s financial and emotional resources are finite. If you’re always living on the edge, it can take so much energy to navigate your way from one crisis to the next, you have nothing left for self-care.

“One way of understanding this is to look at the idea of ‘treatment burden’,” says Andrea Williamson, a Deep End GP and a clinician at Glasgow’s Hunter Street Homeless Services.

“Say you have type 2 diabetes and you have to think about what you are eating and when you are eating it; you have to think about how to lose weight, work out an exercise regime – well, all of that takes money and effort.”

It’s difficult to stick to a healthy diet if you are struggling on benefits and the price of fruit and vegetables is going up. Or if you’re using a food bank and everything comes in tins and packets. Just as it’s difficult to keep exercising if you have no safe open spaces nearby – or, indeed, no free time to use them.

“One of the horrific things about modern Britain is in-work poverty,” says Williamson.

“You might be taking on extra hours, you might be on a zero-hours contract. How can you stick to an exercise regime if you have no idea if you’re going to be working tomorrow, or if you’re going to be earning money this week?”

Williamson also runs a clinic for women in alcohol and drug recovery, where attendance is erratic. “Sometimes life just overwhelms them,” she says. “Sometimes their mental wellbeing is so poor it’s impossible for them to turn up to appointments or even answer the phone.”

But not turning up for appointments can be deadly. Recently, the GP led a study which examined the records of more than 500,000 general practice patients in Scotland.

“We found that those who had missed two or more GP appointments in the preceding three years and had mental health and substance issues were eight times more likely to die than those who hadn’t,” she says. The figures were less stark for those missing appointments for physical conditions alone but there were still excess deaths.

“We used to think that if people didn’t turn up, it meant they didn’t really need medical help,” Williamson goes on. “Our research blows that out of the water. These are people with unmet healthcare needs. We need to work out what we can do better.”

Deaths of despair

In the US, the rise of such “deaths of despair” – that is, lives directly lost to suicide, drug overdoses and alcoholism – in less-educated white communities was at points during the 2010s so marked as to drag down average life expectancy across the nation as a whole.

Here in the UK, at least in the nationwide picture, we are not there yet. But none of the trends is especially encouraging. Recorded suicides were creeping up in the immediate run-up to the pandemic before edging back down in the singular circumstances of the lockdown. Alcohol deaths in both Scotland and England increased after the virus arrived.

It is rocketing drug deaths, however, that truly set Scotland apart, leaving it with the highest per capita rate in western Europe (drug deaths in England have also risen sharply since 2012, up by around 80%, but from a far lower base). The record Scottish drugs toll in 2020 of 1,339 was 5% up on the previous record – set in 2019.

The Scottish Government’s declaration of a national emergency has made little impact: the 2021 figure was almost unchanged, at 1,330. Look at graphs of these deaths over the past decade and the gap between rich and poor opens up like a menacing jaw: those living in the most deprived fifth of areas across Scotland are now fully 15 times more likely to leave the world this way than those in the least-deprived fifth. And Glasgow is the second-worst-hit city – only Dundee fares worse.

In Drumchapel, our links practitioner Lorna Robertson is crystal clear: “People are dying prematurely of physical conditions but also of overdoses and suicides.”

And every Deep End GP I speak to lost patients to substance abuse during lockdown. There were many relapses as Community Addiction Teams stopped making visits, recovery cafes closed their doors and Alcoholics Anonymous meetings moved to Zoom.

Nowhere was this plainer than in the blackest of all Glasgow’s health blackspots: Govan.

At GalGael – a charity which runs woodwork courses for men with physical and mental health difficulties – I find Francis Corkhill chopping timber. Inside, rows of workbenches stand to attention on a floor carpeted with wood shavings. Scattered around are fruits of the men’s labours: bowls and boxes so smooth you yearn to run your fingers along them.

Corkhill wipes his hands on his overalls and comes to talk to me. He is so diffident it is hard to picture him in his gobby glory days, when – as he explains – he used to flog computer games down the Barras, Glasgow’s famous market.

He says his physical health is good for someone of his age, 57. But as he talks, he lets slip a litany of ailments. His high blood pressure. His anaemia. And, not least, his yearning for escape. A former heroin addict, he did not relapse during the pandemic but he did start drinking. Just a couple of glasses of wine a night, he says, at first. Then a bottle. Then maybe two.

“I was on my own during lockdown,” he says. “I felt quite isolated. I got into a routine of drinking while watching Netflix. It was more enjoyable with a drink. I think alcohol is very difficult. It is a social drug, so you don’t see yourself as having a problem.”

And does he have a problem? He hesitates. “It’s not physically addictive for me. I don’t shake if I stop. But yes, I think I may have a problem. I know I drink too much.”

The drinking worsens Corkhill’s anaemia. “I don’t eat properly,” he says. “I do cook sometimes. I make pasta and throw in some broccoli and potatoes. But right now, it’s about not having enough money. Because I am still buying the wine. One bottle a night. That’s £35 a week. The food tends to come second.”

Govanhill

A visit to Govanhill, the city’s most diverse district, always induces a rush of just-arrived-on-holiday excitement. An area of high immigration – there are said to be more than 40 nationalities squeezed into a square mile – its streets titillate all the senses.

Eyes goggle at the brightly coloured vegetables laid out as if on a market stall. Nostrils tingle at the aroma of tacos and dosas drifting from cafe doors. Ears twitch like radio antennae trying to tune into a myriad of competing languages.

Not yet rendered bland by gentrification, Govanhill is a pleasure to spend time in. Moreover, the neighbourhood, at least as defined in the GCPH Glasgow Indicators Project, is not an especially unhealthy place by city standards. On the league table of male life expectancies, it is in line with the city-wide mean of 73 years, and its women actually live slightly longer than is typical across the city as a whole.

And yet averages can conceal a lot. In the handful of streets most Glaswegians would recognise as Govanhill, there is no mistaking the deprivation. For a long time, slum landlords held sway here. There are still pockets of squalor, and litter piles up in closes. In some tenement blocks, bedbugs are endemic.

Govanhill is both stigmatised and highly politicised. Its large Roma population is a lightning rod for racists who mutter about “gangs of men hanging around on street corners”.

Located in First Minister Nicola Sturgeon’s constituency, it is often weaponised against her. Her critics say she is always talking about her government’s commitment to ending child poverty, yet – at 69% – this patch of land in her own back yard has the worst child poverty rate in the UK. Every so often the police investigate, and dismiss, rumours of systematic child sexual exploitation.

This cocktail of poverty and ethnic tension has implications for those trying to improve the lives of the people who live there. Frankie Rose is a links worker at a practice in Govanhill Health Centre. She says her job relies on building up trust, especially with the Roma patients, many of whom have multiple health issues but are wary of authority.

“A lot of Roma women wouldn’t come to the surgery during Covid because they thought they were going to be vaccinated against their will,” says Rose. “They are also suspicious of procedures such as smear tests. The anxiety is understandable. They have experienced so much persecution, they expect to find it here. For them, the threat seems real.”

There are other cultural barriers, too. “Literacy and numeracy tend to be low,” says Rose. “Their health beliefs are very different to ours, and they will trust those in their own community over doctors.”

There is also a double language barrier. Rose often communicates with patients through an interpreter. But very few interpreters speak Romani, so the conversation will be carried out in the language of their country of origin – mostly Czech, Slovak or Romanian, which is their second language. Since Covid, this has been done via telephone, which can be quite stilted.

Even when good relationships are built, they tend to be transitory. “It can be frustrating,” says Rose. “You work to create a degree of stability, and then the patient goes to their home country for the summer. Their benefits are stopped, their tenancies abandoned, they fall off the GP register and when they return, all these things need to be reinstated.”

Govanhill’s Roma and South Asian families tend to live multi-generationally but larger properties are expensive and difficult to come by, so overcrowding is rife. “The worst I’ve come across was 11 in a two-bedroomed flat,” adds Rose. “At the moment I am seeing a family with nine people in two rooms, one of which is meant to be a living room. That family has a baby with complex needs. But having so many people breaches the terms of their tenancy, so they could end up homeless.”

Living like this can make you ill. “These big old tenement flats may already be damp,” says Rose. “If you add to that nine people breathing, cooking, doing laundry – that creates a lot of moisture. Many homes have black mould so you get a lot of respiratory tract infections. Add to that the stress of having no privacy.” One woman Rose sees gets chronic migraines; her kids are constantly fighting.

When Analetta enters the room, she looks in her 50s but is 35 with chronic back pain. Neither she nor her husband is fit to work. They live in a housing association property in Govanhill with very little furniture, no carpet, no table to eat at. But what Analetta wants is a better sofa – one she can sit in with a degree of comfort.

Rose phones a charity specialising in adapted furniture to see if it can provide a sofa but she is told it cannot help unless Analetta is on Personal Independence Payment, a benefit she has been rejected for. She is submitting a new claim, but it won’t be heard for another four months. Rose puts in calls to other charities which say they’ll see what they can do. “There is so much demand,” she says.

Inequalities

We have become so inured to health inequalities, they can seem inevitable but it didn’t – and doesn’t – have to be like this. Regions in many other countries have gone through a similar process of deindustrialisation with fewer aftershocks.

By 2011, the GCPH was highlighting unflattering comparisons between its own hinterland and the Ruhr. That region had once been the heart of German steel and mining production but lost a majority of its industrial jobs between 1970 and 2005.

And yet life expectancy had “been consistently higher” in the Ruhr than in West Central Scotland (WCS). Moreover, lives were shorter in the majority of WCS local authority areas than in Gelsenkirchen, the Ruhr district with the very lowest recorded life expectancy.

When the GCPH analysed the peculiarities of the “Glasgow effect”, it concluded it was rooted in the country’s approach to urban planning in the mid-to-late 20th Century: its creation of the four peripheral estates and its decision to “skim off the cream” – skilled workers – by decanting them to its five New Towns. The city’s heavy focus on council estates became problematic when the Thatcher era ushered in a long squeeze on investment in social housing. This was more true in Glasgow than, say, Liverpool, where the council committed to an ambitious regeneration strategy.

“There was also a greater diversification of industry elsewhere,” says Gerry McCartney, a professor of wellbeing economy at Glasgow University who has worked with the GCPH on major recent research which attempts to move from offering analysis to offering solutions.

“In Scotland, we had companies such as IBM and Caterpillar who were here for a while and then dramatically downsized or moved on. So we ended up with low-paid service industries rather than higher-tech home-grown industries. This created layers of vulnerability which have fuelled drug use, alcohol abuse, suicide and violence.”

Entrenched though it is, McCartney and his colleagues insist the situation is fixable. “Between the 1920s and 1970s, life expectancy increased and health inequalities narrowed dramatically,” says McCartney.

“We know what worked then and we know what is working now in social democratic states. We need to invest in the welfare state, the NHS, council houses and industry. We need to give trade unions greater power and reduce income inequalities.”

The report McCartney has been working on makes 40 recommendations which include increasing benefits and tax credits in line with inflation every

year and the introduction of more progressive income tax bands and rates to narrow income inequalities across society.

It all sounds logical and yet…unlikely. Two days before she arrived in Downing Street last September, Liz Truss complained on the BBC that the “economic debate for the past 20 years has been dominated by discussions about distribution”, before stampeding into tax cuts which favoured the rich.

Market anxieties about their affordability soon forced the abandonment of many, shattering Truss’s authority and unleashing chaos in the Conservative administration but also ushering in yet another drumbeat of demands for “economies” in welfare

and public services from Whitehall.

Nor has the Scottish Government displayed any great appetite for taxing the rich: while the Institute for Fiscal Studies judges that Holyrood has used its powers to make Scotland’s tax and benefits systems more progressive than those elsewhere in the UK, the SNP has steadfastly refused to reform the regressive council tax.

While politicians drag their heels on the fundamentals, clinicians go on doing what they can to improve their patients’ lives against terrible odds. But they, too, can come a cropper on the finances. The Govan Social and Health Integration Project was a four-year initiative whose features included employing two social workers and holding multi-disciplinary team meetings to identify those patients most at risk.

According to Dr John Montgomery, who chaired the project, it was working wonders across the four practices in Govan Health Centre before funding was withdrawn.

“Everyone would have their IT systems open so they could very quickly share information, come up with a management plan and implement it,” he recalls. “What we were doing was highlighting the most vulnerable: children, the elderly, those in need of palliative care.”

The practices also hired two newly qualified GPs, which allowed the existing, more experienced GPs to have longer appointments with the most complex patients. Auditing the effect across the four practices and comparing them with others, Montgomery witnessed a 12% decline in demand for GPs. And yet a bid to extend the project failed.

Since it stopped, demand has shot back up and then some. Before the pandemic, as the funding was ending, the number of consultations at the practice was 1,100 a month; it now stands at 2,000 a month.

But other valuable Deep End initiatives have been adopted – and kept. The links workers are now seen as indispensable. The embedding of financial inclusion workers, like the one Analetta was referred to in Govanhill, is now being rolled out after a successful pilot in two practices in Glasgow’s East End. In the pilot, “they helped patients with financial difficulties access the benefits they were entitled to”,

Montgomery says. “In the year it was running, those workers realised more financial gain for their patients than the surrounding 20 practices combined.”

Heroin

Charities like GalGael and Simon Community Scotland, which runs access hubs and street teams supporting rough sleepers in Glasgow and Edinburgh, tirelessly demonstrate that there is no such thing as a hopeless case.

It is through Simon Community Scotland that I meet Kevin Buchanan, a 50-year-old man hewn from post-industrial blight. Born in Govan as the shipyards were closing, he had a challenging childhood. His father was in jail for much of it, leaving his mother to raise three children alone. By 16, Buchanan was in and out of young offenders’ institutions, then prison. By 19, he was taking heroin.

Over the next two decades, he had periods of stability – times when he was “clean” and in employment. “But when things got bad, I always went back on the drugs,” he says.

A few years ago, things got very bad indeed. One of his two sons took his own life at 23. Buchanan still finds it difficult to talk about this. “The police had taken him home after he threatened to jump in the Clyde,” he says, his voice breaking. “He overdosed on his mother’s medication, and my life just crumbled.”

Buchanan ended up back in jail and then – on his release – in one of Glasgow’s homeless hostels. Surrounded by other users, he started taking heroin again. He has multiple health problems.

A type 2 diabetic, he also suffers from arthritis, anxiety and depression. He rhymes off his medication, adding: “I take 16 tablets in the morning and four at night.”

Cally Archibald, an outreach worker with the homeless charity, met Buchanan when he was collecting food vouchers. “She chased me around town, made sure I picked up my prescriptions and took me back to the community addiction team,” he says. “If I’m honest, it was kind of annoying but she helped me pull my life together.”

Now Buchanan has his own flat. He is back in touch with his mother and sister, who live nearby and sometimes cook him dinner.

Four days a week, he volunteers at the access hub; on a Tuesday, he trains with the Scottish Drugs Forum. His health is still poor but he is taking his medication. He tells me proudly he only has two more buprenorphine injections to get before he’s “clean” again. I check back in after a couple of months, and he is indeed completely off it.

“My flat is great,” he tells me in the Simon Community access hub. “I have done it up by myself, I spend time with my other son and my five-year-old grandson.

“Now I am not buying drugs, I have more money for food. I can spoil my grandson occasionally…bring chocolates in here for the girls. This is the best life’s been for a while.”

This article is extracted from Broke: Fixing Britain’s Poverty Crisis, edited by Tom Clark. The landmark collection of reporting detailing the impact of poverty on Britain is published later this month by Biteback

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe © Beth Murphy

© Beth Murphy © simon murphy

© simon murphy © Google Earth

© Google Earth