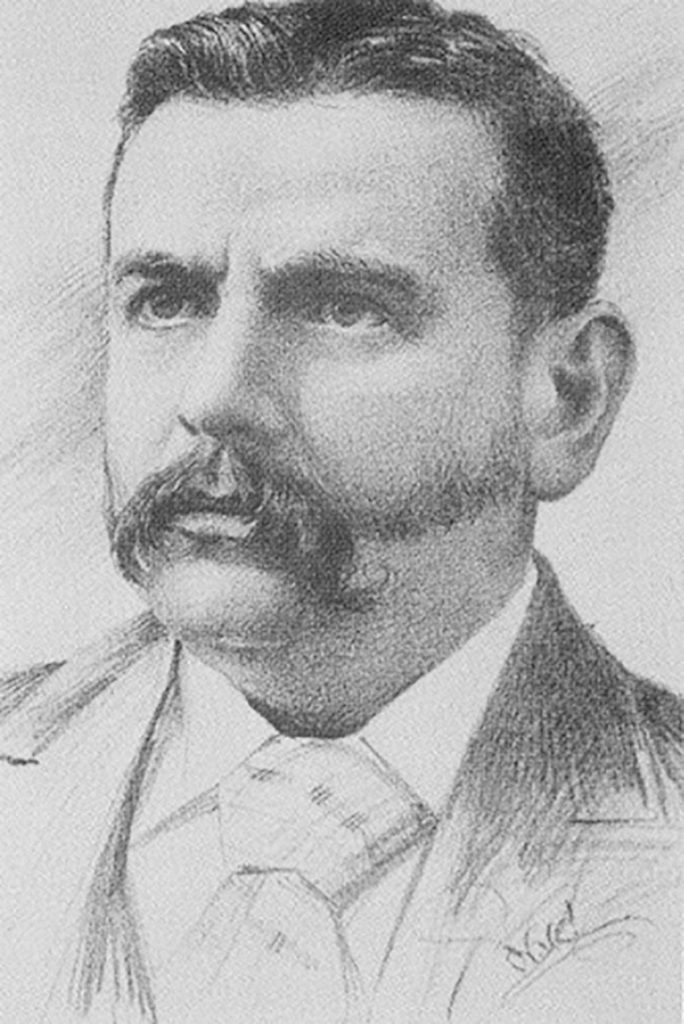

HE was a doctor, an inventor and a visionary.

John Macintyre may be largely forgotten but his pioneering inventiveness has saved thousands of lives.

From making some of the earliest sound recordings of the great singers and actors of the late Victorian era to introducing electric lights to our hospitals and producing some of the first x-rays, he was a remarkable man.

He was also, according to contemporaries in Glasgow, a gentleman.

Born in 1857, Macintyre started from humble origins, the son of a tailor in Glasgow’s High Street. His first job was as an apprentice electrician, or sparkie, but an aunt’s bequest enabled him to study medicine.

These twin interests shaped his early career in gaslit Glasgow. As consulting medical electrician he literally brought light to the wards of the Royal Infirmary.

He also pursued a career as an ear, throat and nose specialist, acquiring a house and consulting rooms at 179 Bath Street.

By 1893, his private practice was thriving. His opinion was eagerly sought by contemporary superstars like Dame Nellie Melba, Sir Henry Irving, Luisa Tetrazzini, Charles and Fanny Manners, and the Polish musician Ignacy Paderewski.

Macintyre fashioned his own recording studio using a phonograph to capture the voices and performances of his patients on wax cylinders. These may well have been the first recordings of Paderewski, then in his early career as a pianist and composer.

He had a wide circle of friends including scientist Lords Kelvin and Blythswood who came round to play with his new-fangled acquisition, a kinematograph from America.

It was this that led to Macintyre’s finest hour.

In November 1895 Wilhelm Röntgen discovered x-rays at his laboratory in Würzburg, Germany, and in January 1896 he wrote asking for help from leading British physicists – including Lord Kelvin.

Although ill, Kelvin was delighted to help and enlisted the support of Macintyre.

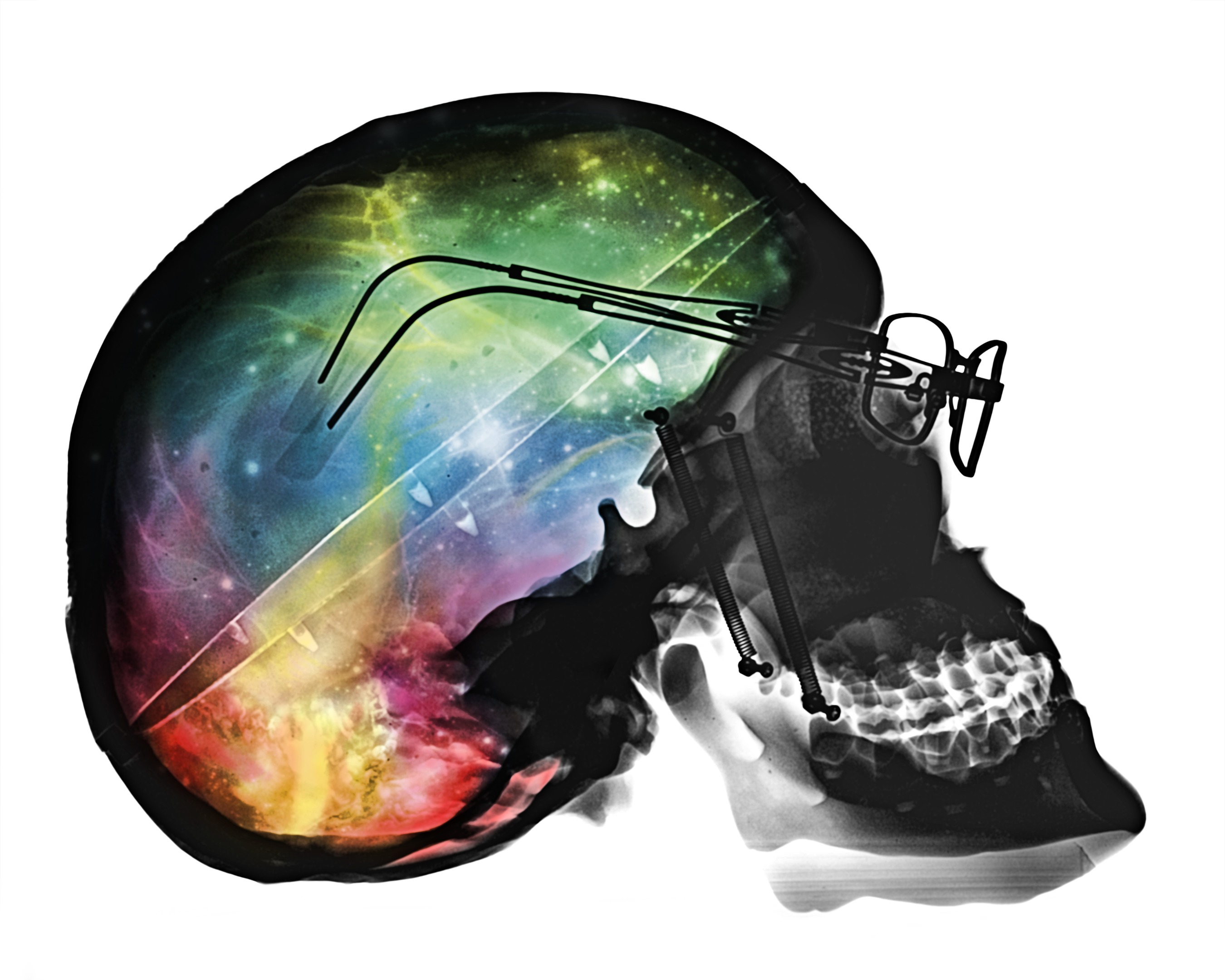

Ever the practical, Macintyre had by March 1896 secured agreement to establish the world’s first x-ray department for patients at Glasgow Royal Infirmary.

He is credited by some with producing the first x-ray photographs of the spine, lungs, heart and kidney. And he made the first moving picture x-ray film which was shown first in Glasgow and then at the Royal Society of London.

Celebrity patients continued to arrive and were sometimes given an x-ray photograph of their hand as a souvenir.

Occasionally they would have tea or go for dinner at the Glasgow Art Club.

Novelist Joseph Conrad visited in September 1898, months before the publication of his masterpiece, Heart Of Darkness.

Fellow writer Neil Munro, author of the Vital Spark with its hero Para Handy, joined them for dinner, listening to Macintyre’s celebrity recordings before drinking and telling stories well into the small hours.

Conrad later recounted: “McIntyre (sic) is a scientific swell who talks art, knows artists of all kinds, looks after their throats, you know. He has given himself a lot of trouble in my interest……

“…. What we wanted (apparently) was more whisky. We got it. Mrs Mclntyre went to bed. At one o’clock Munro and I went out into the street. We talked. I had read up The Lost Pibroch which I do think wonderful in a way. We foregathered very much indeed and I believe Munro didn’t get home till five in the morning.”

Conrad subsequently wrote to Macintyre, inviting him to visit him in England “if bohemianism in a farm house does not look dangerous to you.”

Macintyre’s death in 1928 triggered much mourning but his longer term legacy is mixed. There is a John Macintyre building at Glasgow University but named after another doctor, not him.

Paderewski later came back to Scotland as head of the Polish parliament in exile during the Second World War. Doctors at Glasgow and Edinburgh universities also helped staff a Polish medical school and the Paderewski Hospital based at the Western General in Edinburgh.

Macintyre’s unique wax recordings were kept in an attic in Paisley only to melt in the scorching summer of 1976. Very few films survive from the 19th Century but his x-ray movie is one of them, alongside a fragment, preserved by the New York Museum of Modern Art, of the first cinema advert – for Dewar’s whisky.

Macintyre’s contribution to x-rays was replicated 60 years later in Glasgow collaboration between medicine and engineering. Ultrasound, developed by Professor Ian Donald and Tom Brown, marked the second revolution in diagnostic radiology. It too is now used in every hospital around the world.

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe