There was a time when Scotland’s contribution to cinema was just two words: Sean Connery. Now we have James McAvoy, Ewan McGregor, Kelly Macdonald, Brian Cox and many more; but for several decades of recent history, Edinburgh’s most famous milkman was our lone representative on screen.

Scots still have a great affection for Connery. Not only because he was our James Bond, but for his endearing habit of playing all his characters with a kilt in his voice, even when cast as an Arab desert chieftain in The Lion in Winter or the immortal Juan Sanchez Villa-Lobos Ramirez in Highlander.

All of these choices could probably be justified. Perhaps his Arab had learnt English from a Scot? Maybe Juan Sanchez had spent centuries touring the lochs? It didn’t really matter: Connery’s biggest role was playing the superstar who linked Scotland to the movies, and he made no apologies for it. “If I didn’t talk the way I talk,” he once said, “I wouldn’t know who I was.”

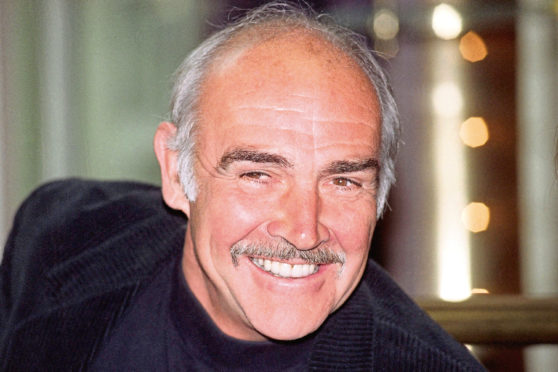

Connery’s brand of old-school masculine confidence was not an act, it was part of him, and perhaps part of the baggage that he has brought with him from his tough childhood in Edinburgh. The background of Thomas Sean Connery has become part of his legend; the son of an Edinburgh truck driver and a charlady, whose early jobs included milkman, coffin polisher, art school model and a bodybuilder who once came third in the Mr Universe contest in the Fifties.

He got his first acting job in the he-man chorus of South Pacific. When he was offered the job, his first question was: “What’s the wage?” The producer airily replied: “It really doesn’t concern me.” “Well,” barked Connery, “it concerns me.” Of course this was not the last time that Connery would get tough about money.

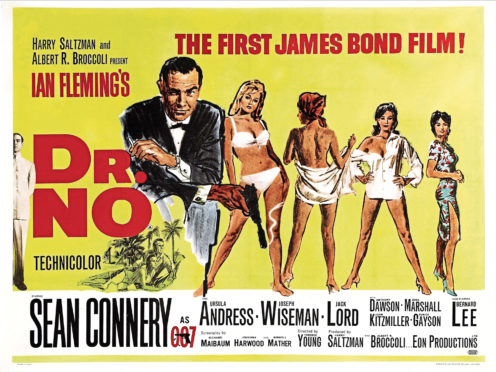

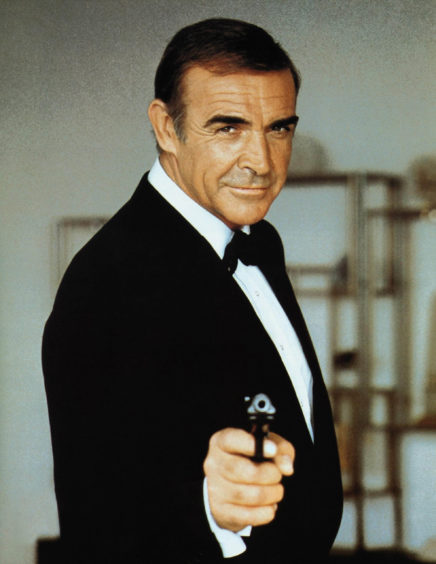

He was most famous for playing James Bond, a role he made his own in seven films from 1962’s Dr No up until Never Say Never Again in 1983 – although he won the role despite the initial disapproval of author Ian Fleming, who would have preferred Cary Grant or Trevor Howard rather than “an overgrown stuntman”.

At first Connery enjoyed the gadgets, girls and guns. “The first two or three were fun,” he said. “The cast made it fun. Jumping out of planes was entertaining, although it was tough on my hairpiece.” Yet Dr No did not make him a superstar; at the time, critics regarded the character of Bond, not Connery, as the driving force behind the series and the actor came to regard Bond as a millstone in his career.

To avoid getting typecast, he altered Bond adventure with other films – Marnie, for Alfred Hitchcock, The Hill and The Offence among them – but although his performances were praised, these films were not big hits. Eventually he quit Bond altogether, regarding it as a monster likely to destroy his career.

Finding success away from 007 was a slow process, but movies such as The Man Who Would Be King (opposite Michael Caine) and Robin And Marian (with Audrey Hepburn), made it clear the qualities that made 007 so successful did not belong to the character but to the Connery.

When Roger Moore took over, Bond continued to be popular but connoisseurs missed the sardonic humour, the cynicism, the bursting masculinity and sheer physical presence that Connery had brought to the part. It was not the Bond franchise that created Connery: it was in fact the other way around.

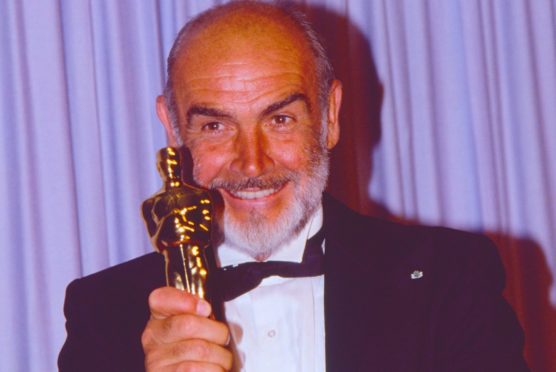

Even so, it was probably not until The Untouchables in 1987 that he again reached, and later far exceeded, the stardom he had first attained as 007. Along with his Oscar-winning performance in that movie, films like In The Name Of The Rose (1986) and Indiana Jones And The Last Crusade (1989) turned Connery into the movies’ most potent father figure – capable, supportive, but not altogether benign. Connery’s own son, Jason, from his marriage to the Australian actress Diane Cilento has never complained about growing up in the shadow of a Hollywood legend, nor the strain of his parents’ bitter divorce, but aside from getting a gofer role on his father’s film Five Days One Summer as a teenager, he says he retained his father’s respect by avoiding using the Connery connections.

With his dark good looks, macho confidence and air of ironic scepticism, Connery belonged to a particular era of masculine stars such as John Wayne and Clark Gable.

“Connery looks absolutely confident in himself as a man,” the film critic Pauline Kael once wrote. “Women want to meet him, and men want to be him. I don’t know any man since Cary Grant that men have wanted to be so much.”

At 60, People magazine in America acclaimed him as the sexiest man alive and despite the increasing years this label stuck to him. Even at 69, he wooed Catherine Zeta Jones – nearly 40 years his junior – in Entrapment and got away with it. Just. Nobody could ever accuse him of being a New Man, either in his professional or his private life. He once told Playboy magazine: “I don’t think there is anything particularly wrong about hitting a woman.” Not a punch, he hastened to add, just a slap. Connery later backtracked, saying he was not advocating violence against women, but the damage was done, and haunted him down the years.

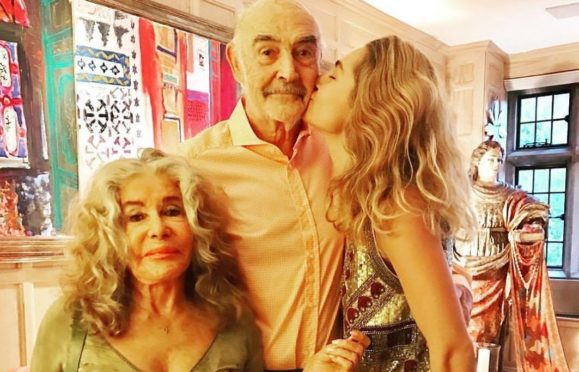

His second marriage, to the French artist Micheline Roquebrune, seemed to give him the stability that this privately insecure man craved, although when they met she spoke no English, while Connery spoke no French: “There was little chance of us getting involved in any boring conversations,” he said later. “That’s why we got married really quickly.”

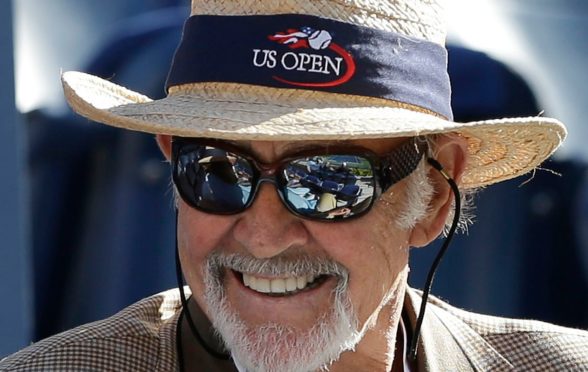

Even less romantically, Sir Sean and Lady Micheline first met on a golf course, the game he has played obsessively since 1962, when he was drawn into the game by his dentist as the ideal means to escape the Bond-mad public. However the longest and most electrifying relationship has been with Scotland, a passion literally tattooed on his forearm. A lifelong supporter of independence, his knighthood was somewhat delayed because his annual £50,000 contribution to the SNP seriously upset New Labour.

The former First Minister Alex Salmond was a particular friend, although on one occasion he dropped in on the Salmonds’ at home so unexpectedly that Salmond’s wife Moira dropped the kettle in fright. The next time, Connery phoned in advance: “Hello, it’s Sean – you’d better hold on to the kettle.”

After retiring from acting in 2005, Connery found a new ambassadorial role as patron of the Edinburgh International Film Festival, bringing a regal glamour to parties and premieres. The festival also revealed a playful side when he hosted the closing awards. Hugging bashful young winners, he teased them about giving him work and was entranced by a clip of Werner Herzog’s Encounters At The End Of The World, where a penguin broke away from the rest of the flock and waddled off purposefully into the unknown. “Sometimes,” confided Connery to the audience, “I feel like that penguin.”

Everybody has a Sean Connery impersonation, but no one can capture the complexity and contradictions of Sir Sean. He was a cocksure man’s man, yet he also wrote a full-length ballet, he was a famous Scottish nationalist who preferred to live in Spain and then the Bahamas, although he returned frequently until ill-health made travel difficult.

He was also capable of enormous financial pettiness, and never forgave the Bond producers for the enormous profits that he felt should have been shared more with him, yet he was also capable of enormous generosity, donating his fee from Diamonds Are Forever to a Scottish Education Trust that continues to pay £90,000 a year to educate youngsters.

Scotland has lost an incredible, irascible, charismatic son who blazed a trail so that others could follow.

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe © Warner Bros/Kobal/Shutterstock

© Warner Bros/Kobal/Shutterstock © Paramount/Kobal/Shutterstock

© Paramount/Kobal/Shutterstock