There is the Communist Manifesto by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, of course. Or Charles Darwin’s On The Origins Of Species. Perhaps the Wealth Of Nations by Adam Smith has a claim to be the most historically influential book.

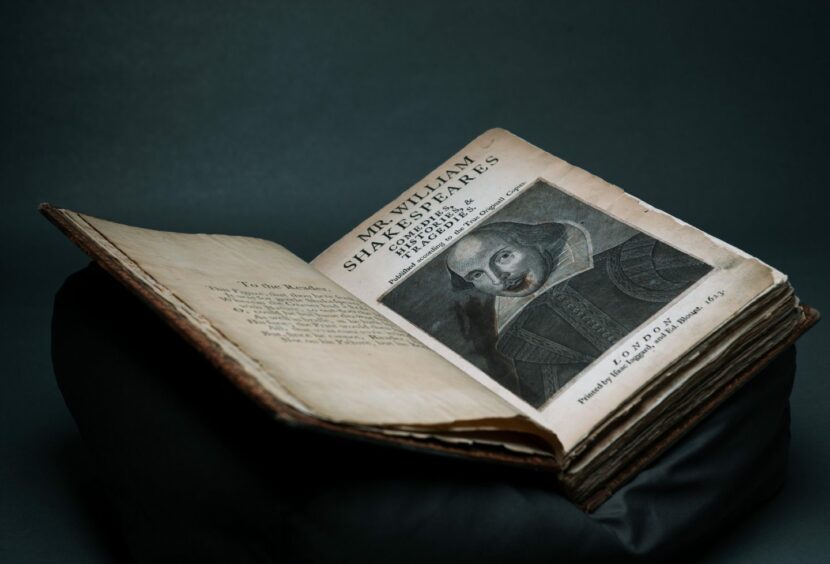

Theatregoers – or anyone with a passing interest in culture – might well choose the First Folio. A compilation of 36 of William Shakespeare’s plays, about half never recorded before, which will soon celebrate its 400th anniversary with rare appearances for treasured copies.

Plays such as Macbeth, The Tempest and Twelfth Night are only staged today because of their inclusion in the book while, without it, other classics including Antony And Cleopatra, As You Like It, The Taming Of The Shrew and Julius Caesar would also be lost.

Prized copies of the First Folio – the first collected edition of his plays and now worth millions of pounds – can be seen by the public in Scotland this year as part of Folio400, a celebration of the 400th birthday of its publication.

There are only about 230 copies, three of which are held in libraries at Glasgow University, the National Library of Scotland, and Mount Stuart House on the Isle of Bute.

About 750 editions of the First Folio were printed in 1623, seven years after Shakespeare’s death. The plays in the collection had been written and performed between the early 1590s and 1613.

“Without the First Folio, we would never have heard anyone say ‘By the pricking of my thumbs, something wicked this way comes’, or ‘If music be the food of love, play on’, or ‘Friends, Romans, countrymen, lend me your ears’, or ‘O brave new world, that has such people in it’, or ‘All the world’s a stage, and all the people in it merely players’,” said Helen Vincent, head of the rare books, maps and music collection at the National Library of Scotland.

“We would never have watched Rosalind and Orlando fall in love in the forest of Arden or a sleepwalking Lady Macbeth try to wash the blood of the murdered Duncan from her hands.”

John Heminges and Henry Condell, members of Shakespeare’s acting company, The King’s Men, put together the First Folio “to keep the memory of so worthy a Friend and Fellow alive, as was our Shakespeare” and present a definitive edition of his plays rather than the many stolen copies that were circulating at the time – pirated much as movies are today.

Before the First Folio, Shakespeare’s plays were printed individually in cheap, flimsy quartos – and 18 of the plays in the First Folio had never previously been printed, even as quartos.

The National Library of Scotland’s copy, which will be on display as part of its Treasures exhibition from late September until March 2024, was donated to the Society of Antiquarians of Scotland in 1784 by Miss Clarke of Dunbar, who Robert Burns described as “a clever woman, with tolerable pretensions to remark and wit”. The Antiquaries donated the book to the National Library in 1949.

“It’s wonderful that our First Folio means we have a link between Scotland and England’s bards,” added Vincent.

The First Folio held in archives and special collections at Glasgow University and used for teaching will go on display at Hunterian Art Gallery on Shakespeare’s birthday, April 23.

“Our First Folio is special because it has been annotated by the owner – someone who went to see the plays with the original cast of actors, including Shakespeare,” said senior librarian Julie Gardham.

“In the cast list at the front of the Folio, the reader has made a note of the actors he or she knows and has written ‘less for the making’ next to William Shakespeare, presumably because the playwright appeared less on stage than the others because he was writing and directing.”

This Glasgow First Folio’s line of ownership can be traced to the Cary family, to Henry Cary, 1st Viscount Falkland, who died in 1633, his wife Elizabeth and their sons, Lucius and Lorenzo, who lived in Oxfordshire and were known to be theatre-going intellectuals who frequently saw Shakespeare’s King’s Men.

“The notes are a direct link to the past and to people who saw the plays being acted as Shakespeare intended,” added Gardham.

The next owner was the 4th Earl of Inchiquin, who bought it in 1808, and after that it was bought by William Euing, a wealthy Glasgow insurance broker, from a Shakespeare expert in 1856. Euing left his library of 12,000 books to the university in his will.

Another First Folio was buried away in the historic library of 27,000 books at Mount Stuart House on Bute, until 2016 when it was authenticated by experts at Oxford University through watermarks and imperfections such as printers’ typos and their inky thumbprints.

This copy belonged to Isaac Reed, a literary editor working in London in the 18th Century. It was uncertain when Mount Stuart acquired it, although mentioned in the 1896 library catalogue and believed to have been bought by the third Marquess of Bute, an antiquarian and collector, who died in 1900.

The Mount Stuart edition is unusual because it was bound in three volumes with many blank pages that would have been used for illustrations.

Elizabeth Ingham, Mount Stuart House librarian, said: “Our First Folio is very well cared for, particularly by the bibliophile 4th Marquis of Bute, who had it rebound in goatskin with gilt lettering and marble endpapers in 1932.”

The First Folio will go on public display at Mount Stuart House between April 17 and May 3 and there will be private viewings available to book until the end of October.

“Shakespeare’s First Folio is important to us as it is such an incredible vessel to use in public engagement and for school groups. We are keen that children can see works of Shakespeare for themselves and be inspired,” added Ingham.

Apart from its cultural value and fascination for Shakespeare scholars, the First Folio is extremely valuable. A copy owned by Oriel College, Oxford sold for about £3.5 million in 2003, while another copy sold at auction in 2006 for about £2.8m. A pristine “complete” copy, with all its original leaves present fetched nearly £7.8m at auction in 2020.

Emma Smith, professor of Shakespeare studies at Oxford University, said: “When we think of Shakespeare, we usually think of his plays being performed on stage. But the written word and the First Folio is central to our understanding of Shakespeare.

“For the first 100 years or so, the First Folio was considered an ordinary book with people doodling in the margins – a copy in Birmingham has cat paw prints and the Folger Shakespeare Library in Washington DC has one with a little girl’s drawings. It is not until the 18th Century that the First Folio becomes valuable and a must-have book for the wealthy elite.

“When Charles II reopened the theatres in 1660, Shakespeare’s plays came back into fashion, and I believe that the First Folio with his plays collected in a single edition was one reason for this.

“Another was that women actors were on stage for the first time and Shakespeare wrote good parts for women. It helped that the women actors spent some time dressed as men and showed a bit of leg.

“It’s an example of how Shakespeare has lasted, not because his plays are timeless but because they are adaptable to different times.”

The First Folio not only gives us a nearly contemporary version of the plays but it is also the only source of the familiar dome-headed portrait of Shakespeare by Martin Droeshout. Without it we would have no idea what Shakespeare looked like.

The preservation of much of Shakespeare’s work depended on the publishers of the First Folio copying, collating and editing from whatever hand-written scripts and first-hand memories were still available in the 1620s.

Professor Adrian Streete, head of English literature at Glasgow University, said: “There are lots of variants of the plays and the idea of an authentic Shakespeare text is very powerful. The First Folio is as close to what Shakespeare wrote as possible.”

The First Folio was the first to divide the plays into three sorts: comedies, histories and tragedies.

Two Shakespeare plays, Cardenio and Love’s Labour’s Won, were not included in the First Folio and are presumed lost forever.

Because corrections were made throughout the printing process, no two copies of the First Folio are identical.

The First Folio originally retailed for about a pound (20 shillings) for a bound copy, or 15 shillings for an unbound copy.

The great 18th Century Shakespearean actors David Garrick, John Kemble and Edmund Kean each owned a copy.

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe © Bbc/Hbo Film/Shakespeare Film Co

© Bbc/Hbo Film/Shakespeare Film Co © Andrew Cawley

© Andrew Cawley