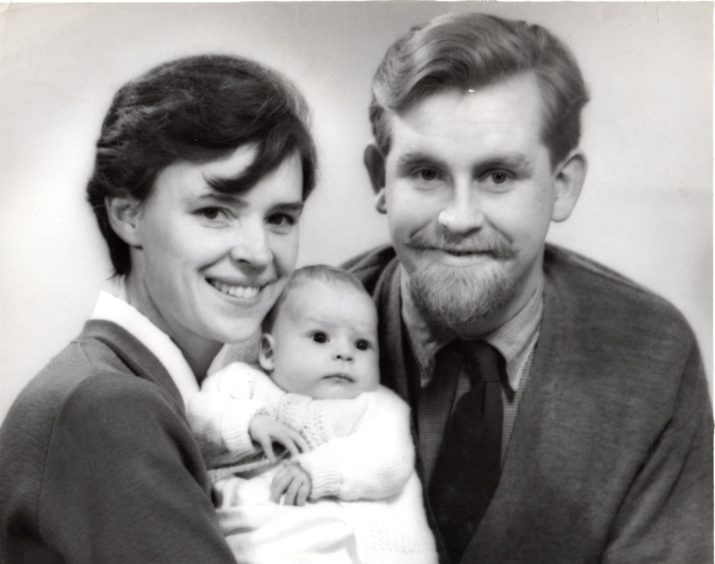

She is the daughter of a Mastermind legend and, after researching her new novel, Sally Magnusson has a new specialist subject.

The BBC Scotland broadcaster and award-winning author could easily go under the spotlight on her dad Magnus’s iconic black chair to answer questions on the engineering marvels that carried clean water more than 20 miles to the slums of Glasgow.

Her second novel, The Ninth Child, plunged her into one of Europe’s greatest engineering feats – the Loch Katrine waterworks that saw hundreds of Victorian workmen blast and bore their way through the mountainsides to help bring an end to lethal waterborne diseases such as cholera.

Sally’s book, which weaves into its plot the supernatural tale of real-life 17th Century episcopal minister Robert Kirke, could not be more timely with a £15.7 million refurbishment of part of the aqueduct scheme under way and due for completion this summer.

Speaking from her 19th century farmhouse on the outskirts of Glasgow, Sally – mum to five grown-up children – told The Sunday Post: “The waterworks and Robert Kirke came before I had the idea for the book.

“I live not far from Loch Lomond and the Trossachs National Park and have for years loved to go there. I used to take the children there when they were younger, and we’d tramp around.

“I loved aqueduct-spotting to see if we could see a glimpse of iron or steel among the trees and finding out about and telling them the story of this water that was taken from Loch Katrine all the way to Glasgow to make people better from the awful waterborne diseases at the time.

“It is one of the most ambitious civil engineering schemes in Europe. I delved into it because I was fascinated. So when it came to writing the book, I already had a lot of the information at my fingertips.

“At the same time, I loved the story of Robert Kirke, a real historical character who was believed in local legend to have been snatched by the fairies.”

For Sally, the clash of Victorian progress and the ancient supernatural beliefs of Highland folk, had in them the makings of great fiction.

The accomplished author, whose first novel The Seal Woman’s Gift was nominated for a string of coveted awards and was both a Radio 2 Book Club and an ITV Zoe Ball Book Club pick, said: “In the way these things do, they were lying at the back of my mind. When I came to decide what I might make my next novel about I thought, ‘wouldn’t it be nice to find a way of exploring them both’.”

She turned to both Scottish Water for information and also to expert William B. Black whose research on “150 Years of Glasgow Water Supply” was a key reference. The Loch Katrine system – made up of two aqueducts that are 25 and 23 miles in length from the loch to treatment works north of Glasgow, today provides about 110 million gallons of water a day, to 1.3 million people.

The first, built in 1855 and completed four years later, was designed to give Glasgow a proper water supply and tackle cholera. It tunnels through mountainous terrain in the shadow of Ben Lomond and bridges over river valleys.

Construction on the second aqueduct and tunnel started in 1885 and was finished in 1901 to accommodate the rapid expansion of Glasgow – then dubbed “the second city of the Empire”. The entire scheme cost £3.2m to build – the equivalent of about £320m today – and was opened by Queen Victoria. The monarch stood above the entrance to the aqueduct near Stronachlachar in October 1859 where thousands of workers and dignitaries had gathered and, according to records, told them it was “calculated to improve the health and comfort of your vast population”.

She added: “Such work is worthy of the enterprise and philanthropy of Glasgow and I trust it will be blessed with complete success. I desire that you convey to the great community which you represent my warmest wishes for their continued prosperity and happiness.”

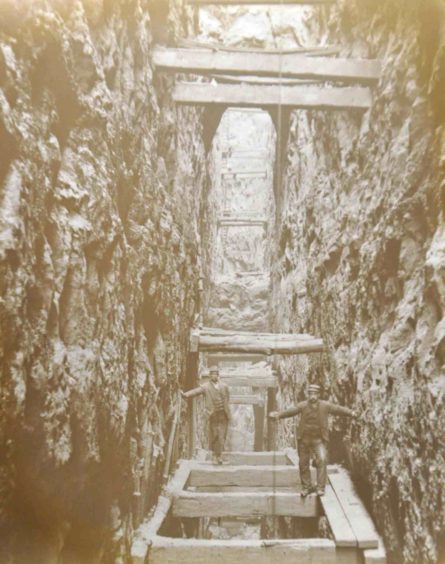

Contemporary pictures of the second aqueduct’s construction were found in a skip during the closure of a Scottish Water office.

Steven Walker, the leakage field technician who found them, said: “The pictures give a fascinating insight into some of the methods used which might appear archaic, and even dangerous, to us now but they were the ‘new technology’ of the day.

“The boom in shipbuilding that helped Glasgow flourish was able to happen because of the two amazing aqueducts that brought water to the two reservoirs at Milngavie and the water treatment works there.

“It’s remarkable to think that the first aqueduct was so successful, and Glasgow grew so quickly, that within 30 years they had to repeat the process and build a second aqueduct to double the output.”

Gary Caig, Scottish Water operations manager, believes the aqueduct system is as relevant and important today as it was then, especially in the light of climate change and sustainability. He said: “The system is still as efficient and environmentally-friendly now as it was then, because it takes water by gravity without the need for pumping.”

Sally, whose mum was renowned journalist Mamie Baird-Magnusson, admits she had never believed she had a novel in her.

“I thought I was a reporter. I did not think I had the imagination to generate from nothing,” she said. “What I have ended up doing in this book is a hybrid, where I still got to do lots of research and I am still able to use people who existed like Queen Victoria and Robert Kirke.

“But I have found that I can generate from within my own imagination in ways that I did not realise I could.”

And what would her dad make of her specialist subject?

She said: “My father came out of the great saga tradition in Iceland, so he was very attuned to what is in effect historical fiction – rooting stories in a specific landscape and a specific time and with characters who were often known to have lived but imagining tales around them. So he would have liked that aspect.

“My father at least would have been my most trenchant but loving critic where my mother would just be proud.”

The Ninth Child is published by Two Roads next month

I’ve started so I’ll furnish: New use for TV quiz hotseat

Broadcaster Sally Magnusson reveals the iconic Mastermind chair – a crucial part of the famous BBC quiz show during her dad Magnus Magnusson’s quarter-century at the helm – is being put to good use in her home, thanks to her husband, director Norman Stone.

She revealed: “My husband runs a youth club in the village. The youngsters come to the house and he has this session where people come and meet them.

“It’s usually any person rash enough to visit us who finds themselves plonked in the Mastermind chair and interrogated by the kids about their life.

“It is used, usually for interrogation. My dad would absolutely love it.”

Sally, who is one of five children, most of whom have worked in TV or radio, says: “We lost a brother when he was a child in a road accident.

“My sister Margaret Magnusson was a TV journalist and worked on Newsnight and now, after having family, has gone to the Citizens Advice Bureau and works in London.

“My other sister Anna is a freelance radio producer and broadcaster, and my youngest brother Jon produces The Graham Norton Show. We are proud of each other.”

And it seems her own kids – aged 34 to 24 – are following suit. The oldest, Jamie, 34, is the TV director behind the New Year edition of Dr Who.

Siggy, a second assistant movie director, has just finished working with Kenneth Branagh on Agatha Christie’s Death On The Nile, while Anna-Lisa has just returned from working in Los Angeles.

Rossie runs Dekko educational comics, and Magnus has his sights set on a career in the video games industry.

Sally laughed: “I told them early on that I wanted a doctor, a lawyer, an accountant – but not a one of them!”

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe