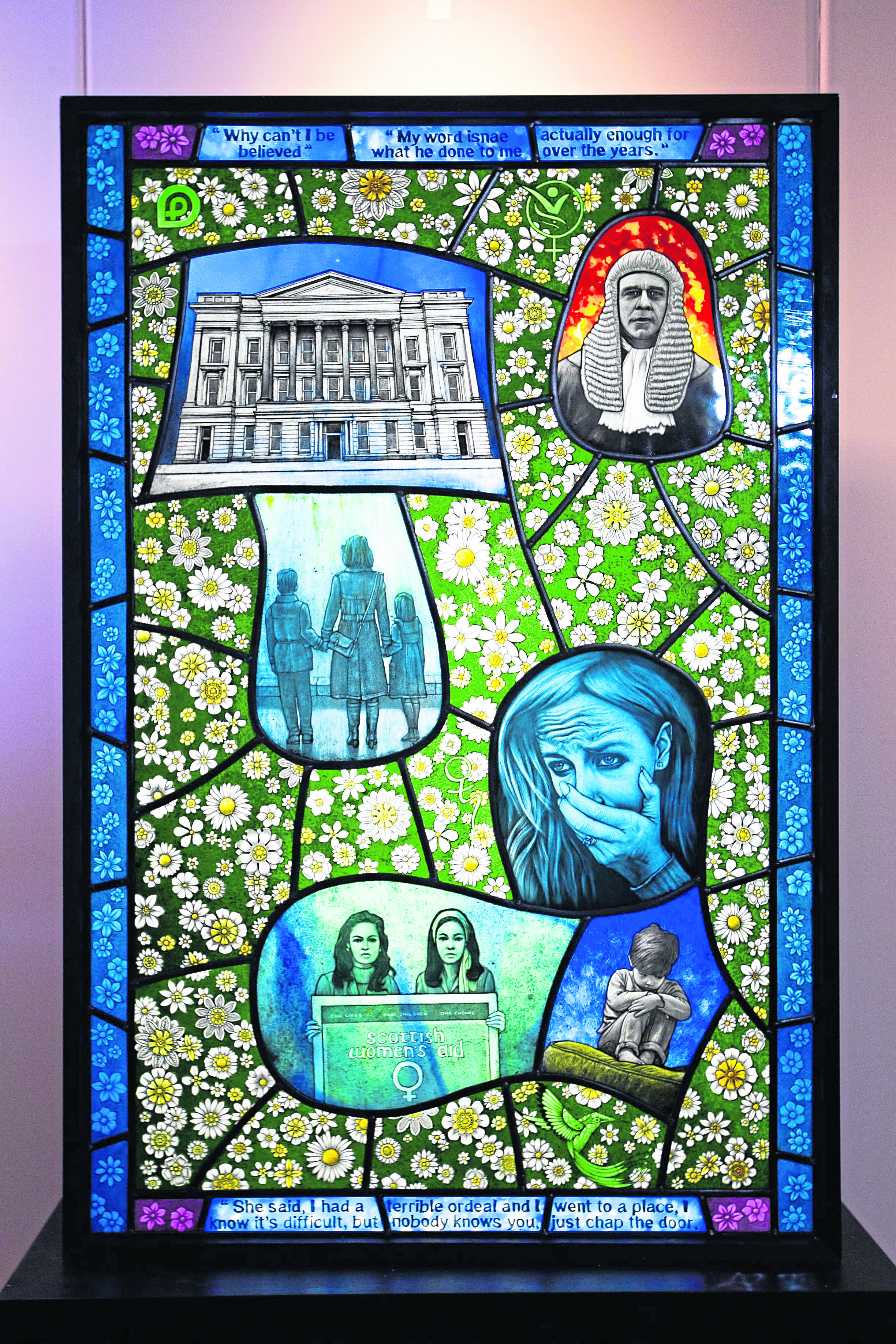

It is a striking work of art, an intricate design of colour and glass.

It is also, however, a powerful image of how women, victims of domestic violence, have struggled to be heard in Scotland’s justice system.

The stained glass, which was unveiled at the Scottish parliament on Wednesday, charts Scots women’s journey through the court system and their battle for justice.

It is the centrepiece of an art installation made by award-winning Glasgow-based artist Brian Waugh and survivors of domestic abuse.

Images and words etched onto glass panels on light boxes includes real quotes from women about their experience of the court system.

The project was the idea of principal procurator fiscal depute Emma Forbes, whose PhD thesis explored survivors’ experiences of the court process.

She said: “Overwhelmingly, the women told me they hadn’t felt heard in that process.

“I wanted to do something to translate the findings to a wider audience so that their words were heard.”

Dr Forbes created a community art project raising awareness of domestic abuse called GlassWalls.

She said: “My PhD described going to court and giving evidence like being behind a glass wall.

“Scotland rightly should be very proud of its response in law and policy to domestic abuse.

“In the 1970s domestic abuse was behind closed doors and we didn’t acknowledge it was happening.

“Now in Scotland it is publicly condemned by society and recognised as a criminal offence.

“Yet when women go to court to give evidence they often don’t feel heard,” she added.

“If they are encouraged to come forward and speak in a public forum but feel not heard, it is like a barrier – or glass wall – because it is seemingly invisible to others.”

The GlassWalls project saw members of the Daisy Project, a Castlemilk-based charity which provides support and advocacy for victims of domestic abuse, learn how to make stained glass panel in weekly art classes.

The group was led by artist Waugh, and together they have created a triptych representing women’s experiences of the justice system.

The first panel includes comments from Dr Forbes’s research, including “Why can’t I be believed?” and “My word isnae actually enough for what he has done to me over the years.”

A second panel will depict the opening of the Scottish parliament, a multi-agency response to domestic abuse and more responsive policing.

The third panel will show a woman looking forward, a more empathic judge and greater transparency in the court process.

One member of the group, Louise, said: “It has been really empowering. We’ve had the opportunity to support each other, to build friendships, to conquer triggers and to have thoughts and feelings validated by what we have been doing with the glass art work. We have become a family.”

She added: “Before many people could read and write, stories were often told on stained glass windows.

“It seemed poignant that while our words weren’t be heard, we could tell our stories in pictures.”

Another member of the group, Christine, said: “It has been emotional to tell our stories through art. It has given us a sense of purpose, and hopefully through telling our stories it will help others.”

The art installation was praised in a debate by MSPs at the Scottish parliament on Wednesday.

Rona Mackay, who is the co-convener of the cross-party group on men’s violence against women and children, said:

“I am sure that I speak for everyone in

the chamber and everyone watching when I say, we do believe you, and your word is enough.”

The artwork is on display at Glasgow City Council chambers this week.

Women most at risk in the year after escaping violent abuser

by Marsha Scott, CEO of Scottish Women’s Aid

To help protect women from violent partners, there are things that can be

done in the long-term but there are things that can happen right now.

One of the best indicators of lethality in a domestic abuse situation is coercive and controlling behaviours.

Scotland has by far the best law around criminalising coercive control.

But generally the risk assessment that is being used across Scotland by police and other partners tends to be insensitive to coercive control. Research done by the College of

Policing in England and Wales looked at this. They have tested an improved version of the risk assessment system which is used widely in the UK.

Introducing that is something we should be looking at very carefully in Scotland.

Another thing is that when we talk about these murders as happening in private, that’s a bit of a misconception.

They do happen in private, they most often happen in people’s homes, but people have this assumption that they happen between people who are still in a relationship and living together.

But actually they often happen in the victim’s home but that doesn’t mean the perpetrator was living there.

The time women are most likely to be killed is some time in the year after they try to leave the relationship.

So often our systems say okay, she’s in a refuge or he’s moved out, the family are safe, so they walk away and do something else. Then the longer-term issues have to do with two big things. Women are not always confident to go to police.

If they have children they know a report will be made to social work, so they’re at risk of having their children removed even though there’s nothing they’ve done. That has a hugely chilling effect on women’s ability to disclose. But also there’s the salami-slicing of budgets at local level.

We’ve just completed a funding survey and it’s very obvious to us that the trend we’ve seen over the last five years is continuing. More than 50%, and probably up to 70%, of our services have seen cuts which have meant that they’ve had to let staff go, they’ve got waiting lists, a whole series of things that mean that women will have less support and protection.

The final thing is that domestic abuse is a cause and consequence of women’s inequality. Women’s choices are greatly constrained by being poor, by not having much power and by being unrepresented at those tables which decide whether childcare is going to be available and whether local services are going to be cut.

The longer-term fix is to pay attention to delivering better equality. If you’re not at the table, you’re on the menu.

The artwork will go on permanent display next year with updates at www.glasswallsart.com

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe