Where once the answers to life’s vast and varied questions were detailed in tiny font, printed on thin, delicate paper and bound in leather, today curious minds need only click a mouse or scroll a screen to fill any gaps in their knowledge.

Updated twice every second, with an average of 572 new articles per day, Wikipedia has fast become the world’s go-to source for information, relegating the traditional print encyclopedia to the dark corners of attics and dusty shelves of charity shops.

However, argues author and journalist Simon Garfield, to dismiss the tomes that once shaped our understanding of the world would be to deprive ourselves of the richness of history’s knowledge – after all, information is not necessarily the same as wisdom. “A Dickens, Jane Austen or Neil Gaiman novel would always be worthy of a place on our bookshelf because, while fiction goes in and out of fashion in terms of its popularity, it’s always set in time,” he explained.

“It’s only with encyclopedias, and maybe with dictionaries, that we think, ‘Oh that’s old knowledge and it has no value’ – it can go to a dump or be recycled, made into modern art or even burnt. But there is so much wonderful stuff to be discovered, beyond just the up-to-date information.”

And Garfield should know. For the past few years the writer has been, as he describes, “hooked on old knowledge”, slowly and dutifully collecting secondhand encyclopedias, often for as little as a few pence an edition, which now litter his home office.

“Can you see the piles over here?” he asked while adjusting his webcam to show the heavy books stacked on top of straining shelves and heaped on the floor. “I can promise you, this isn’t even the half of it. The actual physical feat of getting all those incredible experts – Nobel Prize winners, famous people and professors – to write about something they knew if not better, but as well as anyone else, is extraordinary.

“To have all that in one place on very thin, onion-type paper, and have access to that, is an extraordinary thing – and a lot easier in some ways than getting that information online. You can get information online but, if you want more interesting stuff, often encyclopedias, especially some of the classic Britannica editions, will do that much better.”

Far from just an inexpensive yet time-consuming hobby, Garfield’s collection of hardbacks has formed part of the research for his new book, All The Knowledge In The World, which explores the history of encyclopedias, from modest single-volumes to a 11,000-volume Chinese manuscript.

The book started life as an article about the 20th anniversary of Wikipedia, written for Esquire magazine, and explores everything from how Encyclopaedia Britannica came to dominate the industry to the door-to-door salesmen that preyed on the fears of parents. Encyclopedias, he writes, were a publishing achievement like no other, shaping our understanding of the world and providing access to information from revered experts that once would have been reserved for the educated elite.

“At the time of the Chambers’s original three-volume encyclopedia, for example, our knowledge of the world was expanding so fast,” said Garfield, whose previous books include Just My Type, a fascinating deep dive into the world of fonts and typefaces.

“Great exploratory voyages, the birth of the Industrial Revolution, there was clearly something in the air and things were beginning to change.

“There were just too many books about too many specialist subjects, so why not combine them? Bring all the knowledge into one place, three volumes, and that would be all you needed – until the next volume would come out, of course.

“People didn’t have book collections unless they were super rich, so an encyclopedia was seen as a way of appeasing a new educational class and a newly emerging middle class. That persisted for quite a long time. It was the education that was important, and that was still the case when big marketing campaigns started in the late 19th Century.”

It was during the 1950s that the encyclopedia started to be marketed as an essential tool for “educating one’s offspring” – a selling tactic that kick-started the trend for a once-revered product gaining a bad name.

“There were so many different brands of encyclopedias at that time,” said Garfield, “and there was a feeling of the selling on the basis of guilt. Salesmen would say, ‘If you don’t get this book, you will fall behind – your children will just not be as smart as little Johnny down the road whose parents have bought it’.

“What parent wouldn’t respond to that? I’m sure my parents, when they bought their set for us, thought exactly the same thing. Encyclopedia salesmen gave that product a really bad name yet most, if not all of them, were really great things to have. It’s just they were sold to the wrong people and sold too hard.”

Of course, since the invention of the internet, 24-hour news and instant updates, the encyclopedia has become something of an obsolete technology. Yet, according to Garfield, looking back at what we knew in the past is still relevant to our future. “You get a historical backstory or hindsight into the way we wrote, the way we thought about things, our attitudes – and, obviously, now some of those attitudes are horrendous,” he said. “It’s an incredibly interesting thing to look back on.

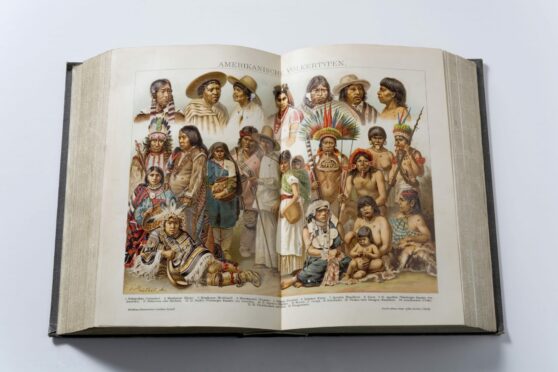

“If you pull one out for someone who isn’t necessarily as interested in encyclopedias and their history as I am, they do still have a slightly magical element and appeal due to their size, the small type, and the illustrations that are great and detailed and very funny. Plus, the fact they are so all-encompassing.

“Looking at encyclopedias, we also learn quite a lot about how we’ve come on, how we’ve developed and how we’ve, hopefully, become…I was going to say woke, but perhaps just more decent, understanding and intelligent in the way we treat other people.”

He added: “Wikipedia is this indefinable cloud-based collection of millions, billions of words that you can never possibly hope to really understand in its entirety. I don’t want to sound like a technophobe or someone who doesn’t like the digital world because, as a writer, it has saved me so many trips to libraries!

“But I loved writing the book because I found out so much and, in my research, I felt I was getting the value that people had when they first got their original encyclopedia. If the book has encouraged anyone to not chuck out their encyclopedias for a few more years then, hopefully, I will have achieved something.

“My own copies are beginning to clog up my office but I certainly won’t be getting rid of any of them. There’s clearly no way I can sing their praises for 400 pages, and then just bring them down to the Oxfam shop.”

All The Knowledge In The World is out now.

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe © SYSTEM

© SYSTEM