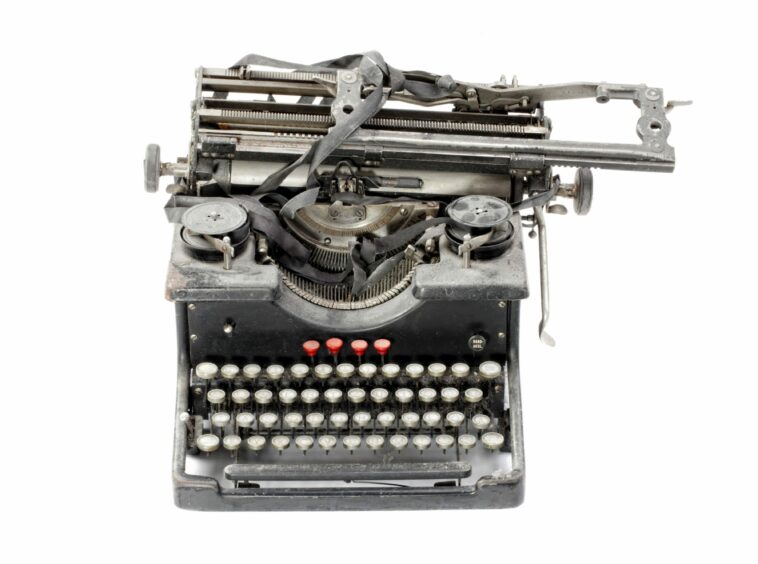

It was a breakthrough, a marvel of new technology, a revolution of the printed word, the typewriter.

And, like transistor radios and vinyl records, their clackety keys and inky ribbons are said to be having a moment as millennials discover the joy of typing on paper instead of pixels.

Alison Taubman, principal curator of communications at National Museums Scotland, has shaped The Typewriter Revolution, an exhibition celebrating typewriters, and insists they are not confined to the history books just yet.

“What we’re seeing is that typewriters are making a comeback,” Taubman said. “There is a young generation getting into typewriters, either because they’ve spotted one in a charity shop or on eBay or in their granny’s loft and they are fascinated at discovering this technology that doesn’t rely on wires or wifi.

“Just being able to disconnect from the digital world is a novelty and something they enjoy.”

The exhibition, at the National Museum of Scotland in Edinburgh, showcases a selection of the museum’s typewriters, as well as some borrowed machines, to chart the history of the typewriter’s social and technological influence over more than 100 years.

“Typewriters were such a big part of our lives,” Taubman said. “The exhibition starts on quite a significant date – April 27, 1876 – when there was an article in The Herald that introduced its readers to a writing machine. They called it a Type Writer. That’s when the first shipments arrived in Scotland from the States.

“When typewriters arrived in Scotland in 1876, they were very expensive. Not many people could afford one. Buying a typewriter then was the equivalent of buying an expensive car today!

“From then, they developed from heavy industrial machines to portable plastic and electronic models – and significantly changed the lives of working women in particular, in lots of different ways, from working as typists and secretaries to starting up businesses training others to become typists, to action on the Suffragettes campaign.”

Visit the #TypewriterRevolution exhibition at the National Museum of Scotland and be sure to tap into more on the history of the typewriter here: https://t.co/WeJVvoWdfi pic.twitter.com/OwxPv4gnTy

— National Museums Scotland (@NtlMuseumsScot) October 22, 2021

Taubman says almost every machine – right up to those used by modern-day typewriter artists and street storytellers – has a back story to it, with many Scottish links.

“We have tried to use these personal stories to illustrate the impact typewriters had on people’s lives,” explained Taubman.

The exhibition looks at typewriters before 1876, when some didn’t even have a keyboard, or had a different layout from the qwerty one we are familiar with today.

“People were trying to come up with all sorts of writing devices before 1876,” Taubman said. “In fact, probably up to 100 years before that. One example we have was made by Peter Hood of Kirriemuir. It’s a device for printing on paper. There’s no keyboard, just a big dial you turned to get the letter, then pressed. Only three of these survived and we have managed to borrow one for the exhibition.

“John Cox from Edinburgh came up with a similar idea.”

Included in the display is a Remington typewriter gifted to the museum in 1904. “By then, it was 30-year-old technology,” Taubman said. “It’s very fancy, a bit like a sewing machine. It has flower transfers and a qwerty keyboard that was established early on.”

The typewriter belonged to Ethelinda Hadwen, the first person to start up a typing office in Scotland. “You could take a handwritten document and have it typed up,” said Taubman. “Ethelinda, who trained in typing at one of the very first typing schools in London, offered the service from 1886, then started opening up training offices for typists.

“She was involved in all sorts of organisations trying to promote women’s employment. It was very difficult for women to find employment. Middle-class women had the chance of becoming maybe a teacher or a governess but not much else because it was not the case for women to work with men. Clerks and bookkeepers were male jobs.

“People like Hadwen could see the link between typewriters and women who had an education and could operate these.

“Between 1880 and 1900, typing jobs went crazy. Women saw the opportunity either to become a typist or start up a typing school, or a business that involved typing.”

And this movement, Taubman said, was instrumental in driving forward the Suffragettes Votes for Women Campaign: “A lot of women learning to type were interested in women’s role in society and the Votes for Women campaign. It seemed to come as the same package.

“When the Suffragette movement really got going, between 1905 and 1910, we had these women trained as typists and business women helping to run a successful propaganda campaign for votes for women.”

Other Scots stories include that of John Deas, who could see the potential business opportunity in typewriters. Interested in technologies, he sold them from a shop in Dundee, along with cash registers and sewing machines, to customers across the globe.

Deas once said: “The typewriter will do for ink and paper what the sewing machine has done for the needle,” – and he was right.

Thousands of others worked in typewriter factories in Glasgow, which exported the machines worldwide.

In fact, Remington-Rand in Hillington is where Sir Alex Ferguson took a job as an apprentice while he began his football career – and where Taubman believes he met his wife.

“It’s been interesting to see people come to the exhibition,” she said. “Of course, the children have no idea what a typewriter is. They’re so used to mobiles and tablets that it’s a strange concept. And then we have the parents and grandparents who reminisce about their days as a typist or a secretary or using a typewriter as a big part of their job.

“And then, of course, there’s the twentysomethings who have this new interest in the old machines.

“But everyone is enjoying it.

“There’s something about the simplicity and immediacy of typewriters that has an appeal. You can’t edit or backspace – and your thoughts appear on the paper as they are in your head.

“People now see it as something very personal. For example, if you type someone a letter, you really have to think about it before you start writing.

“Typewriters are nostalgic, but people are using them now in a different way from when they first appeared. They are finding creative uses, such as typewriter art.

“The fact is typewriters are a huge part of our history but they’ll probably still be around for a long time to come.”

The enthusiast

The child of two journalists, Tom Hodges spent his early days surrounded by typewriters.

And during a gap year in Paris working at a bookshop with typewriters, he taught himself how to repair them after watching countless YouTube videos.

Hodges is now the owner of Typewronger, a small bookshop in Edinburgh, which houses Scotland’s only typewriter repair shop too, and typewriters for customers to try.

And he is an avid collector, with over 100 machines, dating back to 1890. He has typewriters in a variety of languages, including Greek, Ukrainian and Turkish – and even some without the traditional qwerty keyboard that is familiar today. Hodges loves the art of a typed letter. He writes to pen pals and has written to a few celebrities too.

When he was about 10 years old, he wrote to Sir Patrick Moore who replied and invited him to meet when he came to host a lecture in Scotland.

And more recently, he wrote to typewriter enthusiast Tom Hanks to tell him about the typewriter exhibition and to invite him to visit the Typewronger shop.

To his amazement the filmstar replied, hailing Hodges a “hero” for keeping the nostalgia of typewriters alive.

“You can send all the emails, texts or tweets, but nothing is more personal or thought out as a letter typed on a typewriter,” Hodges said.

While Hanks hinted that he might come to Edinburgh, Hodges is excited to talk typewriters.

“I’ve seen all his films and read all his books, but to be honest I think our chat would be about typewriters!”

The Typewriter Revolution runs at the National Museum of Scotland in Edinburgh until April

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe