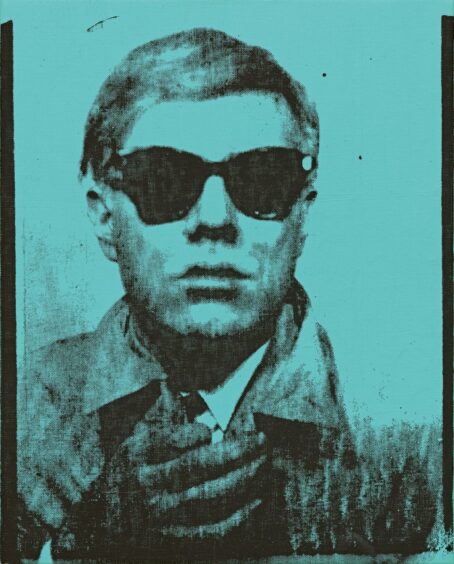

If in the future, as he once predicted, everyone will be famous for 15 minutes, Andy Warhol has spent far longer than most in the spotlight.

From his Campbell’s Soup Cans to The Velvet Underground, the house band at his New York HQ, the Factory, Warhol’s life and artistic legacy continue to fascinate. The leading artist of the ’60s Pop Art movement, he straddled fine art and popular culture like no one before or since.

With his work routinely selling for millions and a three-part BBC series, Andy Warhol’s America, putting his life in historical context, the influence of this oddly shy yet showmanlike artist continues to reverberate.

Warhol may be the best known Pop Art proponent but he was not the first and three Scots – Leith-born Eduardo Paolozzi, Glasgow-born John McHale and William Turnbull from Dundee – were pioneers in the movement that would shape our culture for the next 70 years.

The trio were part of the Independent Group which met regularly at the Institute of Contemporary Arts (ICA) in London from 1952 to 1955 to debate art, ideas and the role of popular culture.

McHale, who grew up in Maryhill, Glasgow, is credited with coining the term Pop Art in 1954. It was soon common parlance among avant-garde artists, writers and critics gathering at the ICA.

According to Keith Hartley, chief curator and deputy director of modern and contemporary art at the National Galleries of Scotland, the artists were as inspired by the engineering of Scotland as the energy of the US.

He said the Independent Group was “mad keen on everything coming out of America” but added: “I don’t think it was coincidental that three of the key artists were Scottish. Many of the lectures and conversations were about new technologies, machines, computers and ways of interpreting the world. Scotland’s dominance in engineering in the first half of the century made the Scots open to ideas for reconstructing the post-war world.

“Warhol was interested in contemporary film and celebrity culture. This also interested the Independent Group, how modern technology had an effect on the way we see things. Photography was crucial in all of this because it reflected the way the world saw itself – the way it was being seen in glossy picture-led magazines from America, which all the artists in the group were interested in, particularly Paolozzi.”

Hartley, who has curated exhibitions about both Warhol and Paolozzi, added: “After the war, Britain was still on rationing and everything seemed grey and depressing. At this point in time America was the top dog. It was seen as a country which had everything going for it.

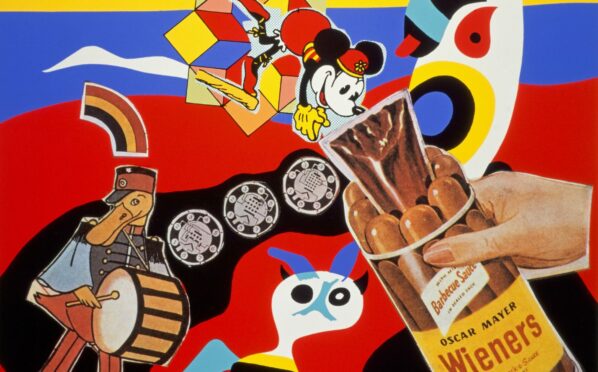

“Paolozzi collected adverts when he lived in Paris in 1947. He scrounged American publications, such as Life Magazine, and collected adverts and cut out all the things that interested him to make collages.

“Back in London, he gave a famous lecture, Bunk, at the ICA in 1952. He didn’t say anything, just showed images; collages and tear sheets of adverts – most from American magazines – projected on to a screen without commentary. You could hear him grunting now and again.”

In 1956 Paolozzi joined McHale, Turnbull and fellow members of the group in a groundbreaking exhibition called This Is Tomorrow at Whitechapel Art Gallery in London.

The brief was to create a single piece of art which as a concept was years ahead of its time. The contemporary art world now worships at the feet of conceptual and performance art but in the ’50s art was either presented on a wall or traditional sculpture.

Paolozzi’s group, which included abstract art pioneer Victor Pasmore, showcased a “summerhouse of the future” created by Paolozzi. This shed-like structure contained photographs of Head Of Man, a collage by Paolozzi’s friend Nigel Henderson, surrounded by a sand patio and collected objects.

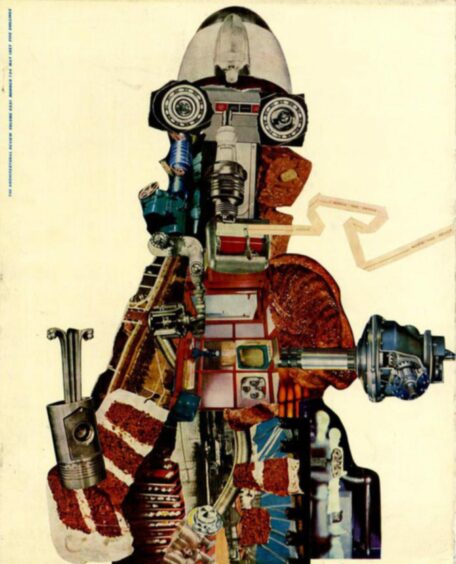

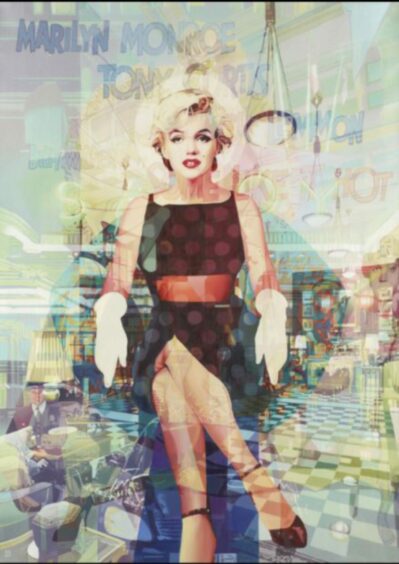

Turnbull’s group created a prefab space-deck roof covered by plastic sheets and plywood. McHale’s used an oversized image of Robby the Robot from the hit film of 1956, Forbidden Planet. Robby was shown carrying off a woman over a spongy floor which emitted a strawberry scent when walked on. Vincent van Gogh’s Sunflower paintings and Marilyn Monroe in The Seven Year Itch also featured.

The ground broken by the Scots would soon be walked by artists who would become better known, including pop artists David Hockney and Peter Blake, famous for designing The Beatles’ Sgt Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band album sleeve, who exhibited at the ICA’s seminal Young Contemporaries exhibition of 1961.

Paolozzi, Turnbull and McHale were all born in the wake of the First World War. Like Warhol, they were from industrial cities and working or lower-middle-class backgrounds.

All earned money in their early careers as commercial artists. As young men who came of age during the Second World War, they considered America to be the “land of milk and honey”.

Turnbull left school at 15 when his father lost his job as a shipyard engineer as a result of the Depression. He taught himself to draw by copying illustrations from magazines. A teacher at his night school art class spotted his talent and he was offered a job as an illustrator with The Sunday Post publishers DC Thomson, working on comics such as The Beano and The Dandy.

Turnbull joined the RAF in 1941 and following the war studied painting at London’s Slade School of Art, where he met Paolozzi, who became a lifelong friend. Like Paolozzi, Turnbull was both a sculptor and a painter.

McHale, whose father was a shop steward, was a scholarly type of artist who joined the Royal Navy at the age of 19 and ended up in Admiralty Intelligence, cross-correlating masses of technical data and analysing code decrypts. He trained as a sociologist after being demobbed in 1946 but continued to be fascinated by art, culture and technology in all its forms. He emigrated to the US with his wife, artist Magda Cordell McHale, and became an academic. He died in Houston, Texas, in 1978.

Like Warhol, Paolozzi was born to immigrant parents, who had fled poverty in Italy to make a new start in Scotland. They ran an ice cream parlour in Leith.

Paolozzi is widely recognised as a pioneer of British Pop Art, a restless innovator who went on to rail against the label, preferring the term surrealist. He, McHale and Turnbull all took their own individual artistic paths as the ’60s ceded to the ’70s.

But nothing happens in isolation in the art world, even one divided by an ocean. A few years after McHale was depicting the iconic Marilyn Monroe in his conceptual art in London, over in New York, Andy Warhol created his first images of the actress soon after she died in 1962.

He would return to Monroe’s image time and time again. In 1968, the Museum of Modern Art organised an exhibition featuring the work of five leading contemporary artists in the lobby of New York’s Four Seasons restaurant on East 52nd Street. Warhol showed six of his Marilyn prints and, alongside, Paolozzi displayed his aluminium sculpture, Marok-Marok-Miosa, with two related silkscreen prints.

It was a key moment in late 20th Century art history, which saw British and American Pop Art collide in one chi-chi Big Apple foyer.

But, as Hartley explained: “For Paolozzi in particular, his interest in the US waned because of America’s involvement in the Vietnam war. It did that for a lot of people.”

For Britain’s Pop Artists, the American dream was over.

Inspired by Warhol, artist hails 1960s icon: He takes the ordinary and makes it into art

Stuart McAlpine Miller has returned time and time again to the work of Andy Warhol who, he says, is a major influence on his work.

McAlpine Miller, who graduated from Glasgow School of Art in 1990, has a large following for his paintings, often featuring beautiful women overlaid with illusionary, colourful, nostalgic imagery, recently launched his latest body of work: a series of paintings based on his interpretation of the Harry Potter books. The 11 paintings, several years in the making, have been licensed by Warner Bros, distributors of the Harry Potter film series.

It came after JK Rowling’s lawyer, Neil Blair, a collector of McAlpine Miller’s work, proposed a series of paintings in collaboration with the movie-makers.

“During the whole pop culture era, the people were promoted,” said the Edinburgh-based artist, currently artist in residence at London’s prestigious Savoy Hotel. “Warhol was a master of self-promotion, in the same way Damien Hirst is a fantastic self-promoter and businessperson.

“You can have the greatest art in the world but unless you are able to promote it then that is not worth anything.

“Warhol took a normal thing and made art out of it. He had a few hundred lawsuits against him but he didn’t care. I’ve always been fascinated by this rule-breaking aspect as well as the power and fame that came with it. He engaged in all that.

“There’s a saying that art is made by working-class people, given to middle-class people and sold to upper-class people. Andy Warhol understood this.”

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe © SYSTEM

© SYSTEM © SYSTEM

© SYSTEM © Paolozzi Foundation /DACS

© Paolozzi Foundation /DACS

© PA

© PA