The vinyl record, a music format once thought dead, has its groove back.

Despite seemingly being ousted from our record collections by CDs and streaming services, sales continue to grow by more than 10% each year since 2006.

Against the odds, Santa will be cramming more 12 inch discs into stockings this Christmas than any year since the 1980s; helping him is Seabass Vinyl.

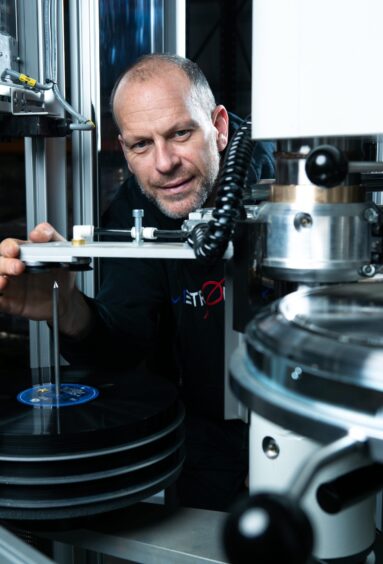

The start-up firm aims to capitalise on the burgeoning market with a brand new record pressing plant, the first and only of its kind in Scotland.

Last week the plant began pressing its first run, made up of editions of two deluxe editions of albums (13th Star, and A Feast Of Consequences) by Scottish artist Fish, a fitting name for a company called Seabass.

The albums will arrive in shops tomorrow, having been shipped from the new company’s property, tucked away beside farming equipment hire firms and a hot tub dealer, on an industrial estate in Tranent, East Lothian.

Seabass Vinyl was created by husband and wife duo David and Dominique Harvey.

After meeting in Manchester, music lovers David, from Dublin, and Dominique, from France, moved to North Berwick a few years ago to escape the rat race.

Getting their own record pressing plant up and running is its own stress, but their excitement shines like the lacquered discs stacked on shelves around the building.

“Vinyl is growing at about 10-15% a year for at least the past decade from a tiny base,” says David. “Lots of people, across all the demographics, enjoy vinyl as a form factor. It is physical as well as a way of listening to music.

“You’ve got a piece of art, a tangible thing in your hands: you can look at the cover, you can actually sit with it.

“The process of listening to music on vinyl, or even CD to a certain extent, is very different to a playlist on Spotify.

“People are looking at vinyl as a way to support smaller artists for whom roughly 50% of their revenue is merchandise.

“One of the reasons we’re doing this is we can get short runs of albums for artists so they can sell them at gigs or online.

“People like Tim Burgess of The Charlatans are big advocates of recognising that smaller artists need that support and encourage people to buy something from them like a t-shirt or one of their physical records.

“It costs so much to make an album and the money artists get from streaming is practically nil.”

Vinyl revival facts

- 12%: Sales of vinyl are up by this amount; they have risen every year since 2006

- 5.5 million: Units of vinyl sold in the UK last year

- 34,000: copies of Lana Del Ray’s Did you know that there’s a tunnel under Ocean Blvd sold so far in 2023, the UK’s highest selling vinyl

- 1 in 4: Albums bought in the UK are in vinyl format

- 35 years: This year vinyl outperformed CDs in sales for the first time since 1988

Seabass aim to produce 20,000 albums per week via two specialist pressing machines, purchased from helpful musical engineers in Sweden.

A puck-shaped lump of vinyl is fed into the device and is pushed flat – with the force of around 175 bar of pressure, or a tonne – onto an imprint of the master disc, with the help of steam pressure at temperatures of 200C.

The disc is then water-cooled and left to rest for at least a day, before being packaged up and shipped out.

At least, that’s the plan.

An alarm, what Dominique and David describe as “the Beep of Hell” stops pressing.

One of the labels you find at the centre of vinyl records became damp and instead left paper residue on the master disc. If the issue is ignored it would ruin the remaining discs.

Production is halted while the engineer, Connor, dives into the pressing machine to retrieve the disc. Someone phones Sweden.

The master pressing disc has to be meticulously cleaned otherwise production halts. Everyone is remarkably calm.

“This is all part of getting started. With a problem like this, we start off with a bit of window cleaner and then go to vinegar,” says David, “and then acetone, then Silvo Polish is your last resort. After that, you’re probably replacing the stamper, but that’s not the ideal solution…”

This involves taking delivery of new stamper discs which could take a couple of days, bringing production to a halt and giving fresh meaning to “like a broken record”.

That would be “not ideal” says Dominique, with a wince indicating this is an understatement.

“One of the reasons David and I are together is because we’ve got that love for music,” she says, as their Irish red setter mooches around big industrial bags of vinyl pellets which will eventually sound like rock and roll.

“When we got together, we went to lots of gigs. We were in Manchester, so there was a lot of music, and because it was Manchester we had some friends who are working in the music industry.

“When David had the idea to buy the presses, I was up for it, straightaway.”

Nestling between the vinyl pellets and cardboard boxes, beside the pressing units, is a record player hooked to sturdy, noise-cancelling headphones; here, the team periodically listens to records still warm from the steam.

While it may look like staff are taking a break this is a quality control measure ensuring the albums Seabass presses are up to scratch, and literally without a scratch.

All being well, the records, once left to settle for a day. The cooling plastic isn’t invincible and opening a door to the bracing hoolie for too long can warp the albums.

The first run we witness last Wednesday is in the shops tomorrow.

Work on the Seabass plant only started in July and, although the building is still without creature comforts, at full capacity it will make around 20,000 records a week.

“We’ve got quite conservative assumptions for the business, and it will depend on things like downtime – production stopping because of things like you’ve just witnessed where we had to stop the process to make sure we got it right,” adds Dominique. “I think we’re at about 50-70% capacity.”

Forthcoming pressing runs include achingly hip artists like The Rah’s and Leo Robinson; there’s another apparently secretive household name lined up which David and Dominique can’t talk about but who does make them smile mischievously.

“It’s very challenging work, but we’re talking to some really interesting people and we’ve had really great support from the music industry in Scotland. It’s really, really nice that people have confidence in us,” says David. “Indicator Records were phenomenal, they were the first people to back us and put money in.

“There are things coming now which are exciting. We have PVC with a lower carbon footprint, and we’re working with Evolution Vinyl.

“They’ve created a new product which is plant-based, and we’re working with them on a test-run and hopefully eventually release records made from their product.”

David’s own origins in music came when he was almost killed after being knocked off his bike by a car as a teenager. Escaping with minor injuries, he used the compensation to buy a record player.

“Disappointingly for my parents I spent the money on a basic but still really expensive Linn turntable,” he recalls. “They were furious! I think they’d have preferred I spent it on something sensible. They’ve come round to the idea now, though…”

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe © Andrew Cawley

© Andrew Cawley © Andrew Cawley

© Andrew Cawley