It is January 14 1978 and Jonny Rotten has only one question for the audience in San Francisco: “Ever get the feeling you’ve been cheated?”

It was the end of the Sex Pistols’ first and last US tour and, indeed, the end of the Sex Pistols as Rotten, soon to be Lydon, abandoned the band even before they returned home to London.

Today, Joe Corré doesn’t feel cheated so much as nonplussed that a movement born in such reckless excitement has turned, 45 years later, into a middle-aged advertising slogan, a vehicle for selling T-shirts, beer and burgers on a Pistols-branded credit card.

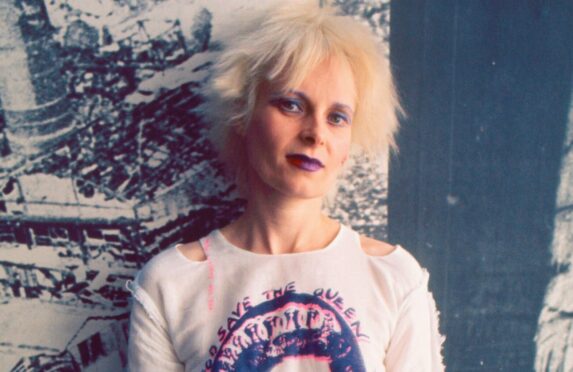

And, if anyone should know, Corré should. He’s the son of punk royalty Malcolm McLaren, the Sex Pistols’ manager, and Vivienne Westwood who, from a tiny shop in London’s King’s Road, effectively invented punk rock.

He’s also the star of documentary Wake Up Punk, premiering at the Glasgow Film Festival today. “Suddenly we’re all punks now and we value what the movement did for the culture of this country,” said Corré.

“It certainly wasn’t what it was like at the time and the celebrations of punk just felt completely hypocritical. But for me, it also felt like an opportunity.

“Punk had a kind of energy about it. And I think all of that got lost with all this trendy celebration and car insurance and Louis Vuitton bondage trousers and McDonald’s punk burgers.”

Wake Up Punk examines the origins of the scene’s values and how the once-terrified establishment now embraces it as, he says, “cosy nostalgia”.

“The purpose of Wake Up Punk is to get people to ask themselves what they really value,” said Corré. “It’s not supposed to be a trip down memory lane about the movement.

“In the ’70s people were thinking, ‘what is my future? I’m destined to either work down the coal mine or a pie shop’. When the message was ‘no future’, young people thought they had a miserable future. The difference is now young people see extinction, through climate change, war and the mismanagement of our government. It’s a different kind of desperation but there are similarities.”

The time is right for people to revive the punk-rock attitude to the establishment, according to Corré , and his mother, Westwood. That includes destroying precious punk memorabilia treasured by collectors.

In a stunt worthy of McLaren, Wake Up Punk features a scene in which Corré sets ablaze records, clothes and posters worth £5 million in a punk viking funeral.

“The film was to really illustrate to people how ideas can become kind of corrupted, compromised, and a hypocrisy to themselves,” added Corré. “That felt like a good ending for it rather than it being auctioned and sitting on some banker’s wall.

“The thing that really upset people wasn’t so much what was being burned because they didn’t even know what was being destroyed. All they got upset about was the idea that it was worth five million pounds.”

Horrified collectors watched as the ashes of the memorabilia were then displayed in a glass coffin in an art gallery and the piece was, ironically, valued at £6m.

Corre kept “some personal items” from the time. He was a 10-year-old living with his mother and father in London when punk exploded and recalls visiting his parents’ boutique shop, the epicentre of the scene, in the mid-70s, in the wake of it being wrecked by football hooligans.

“What I realised as a child very strongly, particularly at the time of the Queen’s Jubilee in 1977, when God Save the Queen came out, is society really hated us,” he said. “We felt very much a target of people’s aggression and hatred.

“I remember as a kid the National Front being outside our house and smashing our windows and posting fireworks through the letterbox. I’d walk down the street and grown men would spit in my face.”

Rather than scarred by it, Corré almost sounds nostalgic. The increasingly popular Sex Pistols would visit his family home and he remembers lying in his bedroom on one bunkbed while the band’s guitarist Steve Jones was in the other telling him jokes and stories. Sid Vicious, he said, was “nice”.

Although the Pistols imploded almost as quickly as they exploded, frontman Lydon went on to found Public Image Ltd, and the punk movement itself drifted from its anti-establishment, anti-corporate, rebellious roots into something his father would dub “cash from chaos,” Corré still looks back at the time with fondness.

“I thought it was amazing to be walking down the road with my mum and have cars crashing next to us because she looked like an alien from outer space. I just thought she was brilliant,” he said.

“The creative industries benefited from the confidence that it gave people to stand up and find a different route for themselves in life.

“It’s a very empowering thing for somebody who suddenly decides, well, I want to be in a band, and I can’t play anything. I can’t even sing. But I’m going to get up on that stage and I’m going to just give it to everybody.

“There are so many people within creative industries and other industries today that wouldn’t be there if it wasn’t for the confidence and the sanctuary the punk scene gave them.”

It was also a movement which allowed people of all backgrounds to express themselves; women, ethnic minorities and the disabled were for the most part welcomed in a scene which celebrated individuality.

“It was a sanctuary for people that didn’t really fit in anywhere else,” explained Corré .

“When I was a kid there were a lot of people around at that time that were affected by thalidomide and I remember quite a few would be punks and it felt great that they belonged to something where they weren’t judged or shoved into a back room. They felt liberated.”

Cosy back-patting and fondly recalling being spat on isn’t a part of the ethos of the movement, however.

“The people who now say, ‘Oh I was a punk, I can remember going to all the gigs’, they just sound like the Teddy Boys of the ’70s. Nothing moves on with that sort of perspective,” he said.

“That’s why I find talking about punk boring and uninteresting. The word doesn’t really mean anything any more.

“It did mean something at one point, but I think now we’ve got to think about other things.

“And that’s why I think activism like Extinction Rebellion is the new punk, because it’s actually standing up and saying no, we don’t agree with this and we’re going to do something about it. It makes the right people furious.”

Wake Up Punk, Glasgow Film Festival, today, 1.30pm

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe