They are mostly used by walkers and cyclists now but many ancient tracks in the Highlands once had a far more sombre purpose.

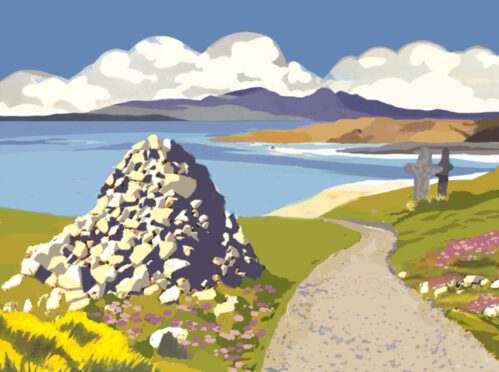

Nowadays the cairns dotted along the mysterious “coffin roads” are the only signs they were once only used to carry the dead to be buried while the living would stick to other routes.

A book, The Coffin Roads, explores the history of these haunting roads that wind their way through the lonely glens towards the seas, and how the old beliefs and customs around death could help us cope with dying and grief more than the modern, more sanitised approach.

The author, emeritus professor of cultural and spiritual history at St Andrews University, Ian Bradley, said: “I’ve always been interested in death and in the spiritual landscape of Argyll, where generations of my ancestors are from. This book is specifically about the Hebridean and West Highland attitudes to death, dying, funerals and burials, which are strikingly distinctive.

“Death is open and involves the community, rather than shut away and private. It is seen very much as part of life, not trivialised, but treated in a matter-of-fact way while at the same time being surrounded by ritual and envisaged as a journey to another state.”

That journey – often long and arduous and taking several days – was along the coffin roads along which mourners would carry the body of the dead. Relays of six or eight men would carry the coffin on their shoulders or on wooden supports, stopping at frequent intervals for rest and refreshment.

“The slow progress on foot from place of death to place of burial could last two or three days and nights and involve several hundred bearers and mourners walking through wild, desolate country with their food, drink and bedding carried by packhorses,” added Bradley.

Cairns marked the places where the bearer parties stopped to rest and may even have provided a platform on which the coffin was rested. Those carrying the coffins would either build a small cairn to commemorate the dead at each resting place or add stones to an existing cairn.

Coffin roads vary in length, with some being short routes between townships and graveyards, while others are longer and more meandering, crossing lochs and the sea like the one that leads to Iona, the burial place for Scotland’s ancient kings and chieftains.

All coffin roads go from east to west for practical and spiritual reasons. On islands, like Harris, Barra and Eigg, the east coast was too rocky and barren for graves to be dug so the dead had to be taken to the west coast machair with its sandy soil.

But ancient beliefs also led people to want to be buried in the place of the setting sun as Celtic mythology held the next world lay in the seas far away to the west. This blessed land of the dead was known in Gaelic as Tír na nÓg (the land of eternal youth), Tír na mBeo (the land of the living), Tír fo Thuinn (the land under the waves) and Tír Tairngire (the promised land).

There were many superstitions. Some Highlanders believed that if the coffin touched the ground, the dead would return to haunt the living, which is why coffins were rested on cairns along the way. And coffins were carried with the corpse’s feet facing away from home so the spirit would not be tempted to return to it.

Coffin roads were often meandering to frustrate spirits, which were supposed to travel in straight lines and a similar reason was given for their propensity to cross running water, which spirits cannot do.

Those with “second sight” had premonitions of ghostly funeral processions along coffin roads, and walkers crossing old coffin roads tell of visions of bloody massacres that took place in the blood-soaked history of the Highlands.

“There was a widespread belief that the dead linger on in the graveyard, waiting for the rest of their family to join them, and that the last person to be buried had to keep watch and look after all those resting there until the next interment. When two burials took place on the same day it was not unusual for each group of mourners to make sure that they reached the graveyard first so that their loved one was not left with the task of looking after the dead,” said Professor Bradley.

Highlanders and islanders who moved away had a desire to be buried among their ancestors – something that happens even today in Barra when family and friends turn out to greet the Oban ferry carrying their relative’s remains arrives.

“Death was prepared for well in advance, with young brides regarding one of their first duties after marriage as being to prepare winding sheets for their and their husband’s interments,” said Bradley.

“When someone was clearly near death, they were visited, tended and ministered to not just by family members but also by friends and neighbours. Semi-professional mourning women might be brought in to sing the death croon over them and ease their passage into the next world.”

After death, the body would be placed in the front room of the house for the two days and nights before burial, watched over by a family member during an often exuberant and rowdy wake.

“These rituals played a key role in easing and facilitating the grieving process. They provided numerous tasks, some of them backbreaking like the digging of the grave and the carrying of the coffin, which occupied people and gave them a purpose and a focus at a time of emotional upset and sorrow,” said Professor Bradley.

“They punctuated the period following death with familiar, reassuring domestic and community activities and created a kind of liminal or threshold space which blurred the hard edges between living and dying and gently eased both the deceased and the mourners into their changed state.

“What the coffin roads and the rituals and beliefs that surrounded the coffin roads testify to most eloquently is an approach to death and dying that was open, holistic, public and deeply healthy. It is a world away from our modern approach where people mostly die in hospital side rooms, their bodies whisked away by an undertaker, sealed in a coffin and, after a period where they lie usually alone and unvisited in a refrigerator or embalmed in a funeral parlour, are transported by hearse to a crematorium.”

Bradley believes that after a century when death was taboo, issues such as assisted dying and the over-medicalisation of death, when the prolonging of life is more about quantity than quality, are being discussed by politicians and the media, brought into sharp relief by the Covid pandemic.

He would like to see everyone have the right to die in their own homes as 70% of Scots would choose. In 2020, David Stewart, Labour MSP for Highlands and Islands started a debate in the Scottish Parliament about everyone having the automatic right to have full day and night care in the last few days of their life, enabling them to die at home.

Bradley said: “People now want to talk about death and what may lie beyond it as long-held inhibitions around the subject are finally disappearing. The approach to dying and death in the Highlands may well have much to teach us today.”

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe © SYSTEM

© SYSTEM © Alamy Stock Photo

© Alamy Stock Photo