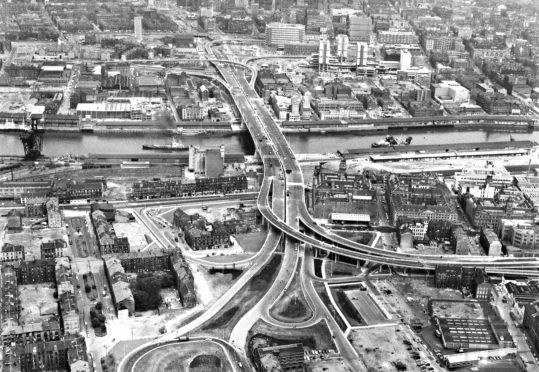

For decades, the Kingston Bridge has been at the heart of Scotland’s motorway network, carrying tens of thousands of vehicles across the River Clyde every day.

Dominating the skyline to the west of Glasgow’s city centre, this month sees the 50th anniversary of the Queen Mother cutting the ribbon to open the 52,000 tonne structure.

The bridge transformed the way motorists travel across the country, reducing dangerous levels of traffic on city streets as part of the city’s ambitious motorway strategy.

Although lockdown restrictions mean there’ll be no official ceremony to mark the occasion, there will be online events to celebrate the bridge which has not only helped inspire similar networks around the world, but has also undergone record-breaking refurbishment work.

Stuart Baird, Bridge Manager with Transport Scotland and chairperson of the Glasgow Motorways Archive, believes the bridge deserves to be hailed as much as its counterparts on the Forth.

He said: “Kingston transformed its city. It vastly improved journey times, and eased horrendous congestion in Glasgow city centre.

“All the roads coming into Glasgow at the time converged in the city centre. You had a lot of traffic coming through and the safety record was poor, and it was difficult to cross roads safely.

“In terms of what the bridge brought to the city, I’d say it deserves much more love.

“The refurbishment and the fact that it’s a concrete structure mean that it will last probably well into the next century.

“Whether it’ll still be taking cars every day remains to be seen, but the structure is definitely a fixture in the city for a long time to come yet.”

The bridge was a vital part of a huge scheme to transform the way increasing motor traffic circulated around Scotland’s biggest city.

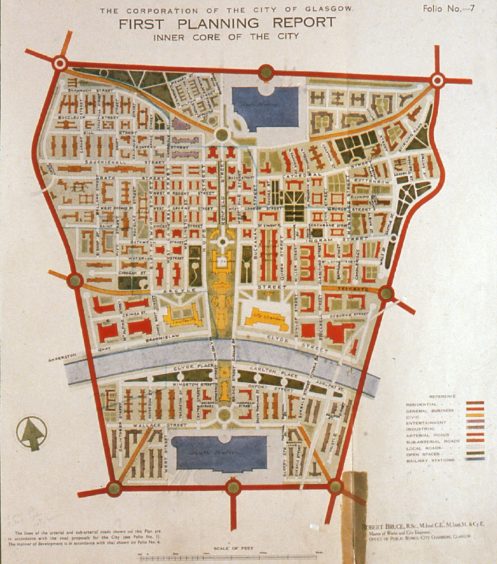

Following the Second World War, the city of Glasgow devised a masterplan for how they wanted to take the transport network forward.

City Engineer Robert Bruce put together a wide-ranging report, which included bold ideas like the Clyde Tunnel and a Glasgow Inner Ring Road – a motorway circling the city centre.

During the 1950s, there was little in the way of money to invest and no progress, but by the 1960s there was budget available to get the city moving more efficiently.

Scott Wilson Kirkpatrick & Partners made detailed plans for going forward, drawing from the highway systems of the US.

In 1961, Detroit was among the cities scouted by officials from the Glasgow Corporation and the Scotland Office to see how public transport and road systems were implemented on a large scale.

“In Glasgow from the outset they weren’t just looking at roads, they were also looking at upgrading the underground, the bus network, and taking trams away,” Stuart explained.

“To an extent, American practice influenced the decision making over here. They knew they wanted a new road network but didn’t want it on the scale of what they were seeing in the big American cities.

“Glasgow having its historic central core meant it wasn’t possible to provide massive multi-lane freeways through the city centre.

“That factored in to the ultimate transport plan that sought to push the majority of traffic travelling regionally or nationally away from the city centre.”

Construction work on the bridge began on May 15 1967. At the time, it was the most expensive highway project ever undertaken in Glasgow, costing around £11m – the equivalent of £200m today.

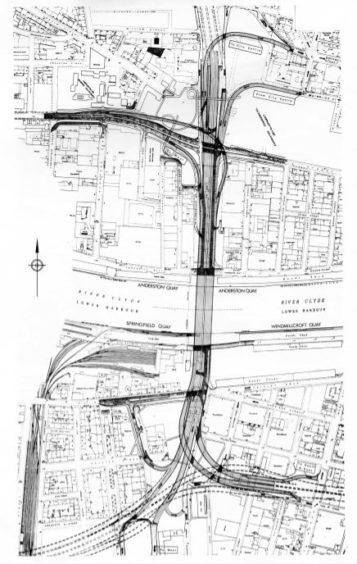

The bridge is made of two parallel structures, joined together with three sections in between to hold it together.

“The scale of it was huge, a massive project,” Stuart explained.

“You’ve got the main bridge and the approaches both north and south which between them have over 100 support columns. It was very different to what had been there prior.

“That whole part of the M8 from Townhead to Kingston involved massive amounts of work.

“It was certainly the biggest civil engineering project in the city centre since the arrival of the railways the century before.”

In 1961, W.A Fairhurst were tasked with designing the new bridge. The initial plan was for a twin deck bridge with quay level & high level decks. The impressions below illustrate how it might have looked. Who thinks this would have been a good idea?#KingstonBridge50 #Glasgow pic.twitter.com/uCmSBi4EbD

— Glasgow Motorway Archive (@GlasgowsMways) June 18, 2020

Were it not for the working river below, there could have been a very different look to the bridge.

At the time, the Glasgow Corporation was keen to have a low level bridge for local traffic crossing between Tradeston and Broomielaw, with a higher level bridge taking vehicles heading across the country.

But the plan was met by opposition from the Clyde Port Authority, who insisted on the need for river traffic to be able to continue as far as the city centre.

As it turned out, ships would end up rarely coming that far upriver, but the low level bridge was scrapped. It wasn’t until the opening of the Clyde Arc in 2006 that the crossing was realised.

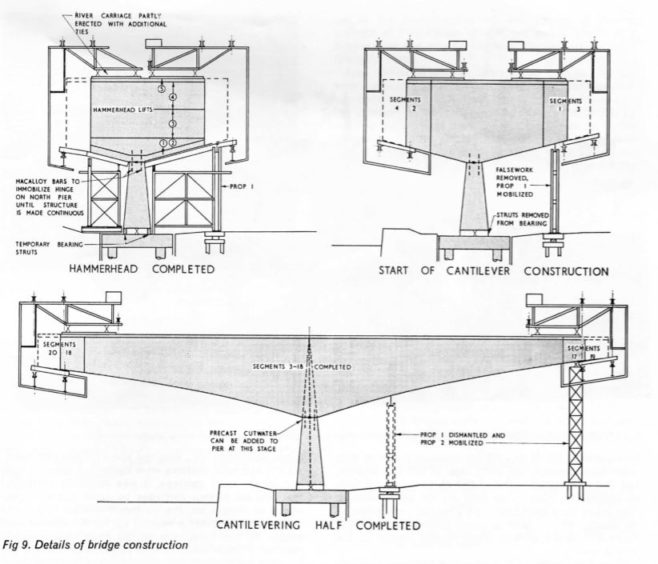

The river and roads below having to remain open proved to be the main difficulty in the bridge’s construction.

“That was what led to the development of the system that they used to build the bridge, which was to cantilever it out from both banks of the river,” Stuart said.

“The method they used meant they didn’t have to put any restrictions below, they were building high above them. It was fairly innovative at the time.

“That’s where the fact that it’s two bridges held side by side comes from. It’s all hollow boxes that were pushed out until they finally met in the middle.

“Two hollow arches tied together with lots of cables and tendons – in construction terms it’s probably one of the most simple forms, but very difficult to design because of the loadings and the traffic that uses it.”

Time for new #KingstonBridge50 photos!

These images show construction of the bridge north approach roads at Anderston in late 1967. Many of the old buildings are still standing today.

Anderston was 1 of 29 Comprehensive Development Areas designated in the city in 1959. 1/3 pic.twitter.com/Kpm2uaLiBF

— Glasgow Motorway Archive (@GlasgowsMways) June 17, 2020

While the Glasgow weather didn’t have too much of an impact on the construction, engineers had to build a new 1.8m sewer from Charing Cross to the river to deal with motorway surface water run-off.

They also put in place an innovative under-road heating system to deal with ice, but it would eventually fail to work in the way it was intended to.

The bridge was opened by the Queen Mother on June 26, 1970 with crowds turning up for the occasion.

“It was a very popular opening ceremony, of all the motorway projects it was the busiest by far,” Stuart said.

“Several hundred turned out and there were so many people that they needed a grandstand for the dignitaries and members of the public were actually invited up onto the carriageway to see the ribbon being cut.

“The Corporation were very proud of it and made it a big affair.

“I think most Glaswegians actually at the time were, if not proud of it, they regarded it favourably. I think they saw it as the future almost.

“They were seeing it as an investment in the city, it was what other places were going to have and Glasgow was getting it as well.”

While only the north and west segments of the original Inner Ring Road plan came to fruition, cities across the world saw what had been done in Glasgow, and many of the engineers who worked on the motorway project ended up working on similar networks elsewhere.

A number of people helped design and build roads in Hong Kong, as well as several cities in Africa.

The Baghdad inner ring road even took a lot of influence from Glasgow when built in the mid-1970s.

Today, the bridge is inspected regularly to ensure it continues to operate.

With five lanes in each direction, it’s is one of the busiest motorway stretches in Europe.

Projections of 120,000 vehicles a day in 1990 made by the original designers were accurate, but at its peak, before the opening of the M74 extension, the Kingston Bridge was taking between 165,000 and 180,000 vehicles a day.

A bridge that takes so many vehicles has specific requirements, like keeping the drains clear, the signs clean and barriers in place.

Serious defects were discovered in the late 1980s, as the bridge wasn’t expanding backwards and forwards as it should’ve.

There were fears in the nineties that it might collapse if strengthening work wasn’t done.

The eventual refurbishment involved the substantial task of a phased lifting of the bridge and shifting it around two inches onto new bearings, work which qualified for the Guinness Book of Records for the world’s biggest ever bridge lift.

“There was a significant amount of refurbishment work carried out from around 1995 to 2005 where the bridge was strengthened and had a number of other works done,” Stuart said.

“When more work is completed in 2021, that will conclude a major project which has been underway for a number of years. The spend on that will probably have been over £50m in the last 25 years.”

Did you work on the bridge? The Glasgow Motorway Archive is looking to collect stories. Visit glasgows-motorways.org.uk

A look to fit the city

Glasgow’s newbuild motorway recruited the renowned William Holford architects to make the network as glamorous as tarmac and concrete could possibly be.

The consulting architects had final approval on how the roads, including the Kingston Bridge, would fit into their environments.

Stuart explained: “The bridge was faced up with certain aggregate panels to give it a nice finish. Under those shiny stone panels are hollow concrete boxes that don’t look particularly nice, so they were aware of that and tried to make it as aesthetically pleasing as possible.

“Engineers tended to come up with dull, drab looking things, but because of the architects, you don’t see a lot of bare concrete finishes on the Glasgow motorway system.

“You’ve always got pebble finished walls, sandstone in some places, others are painted.

“It’s all designed to fit in with the cityscape as much as possible and that was their direct influence.

“They didn’t want to just throw a road through the city centre and hope that it blended in. They spent a bit more trying to make it as aesthetically pleasing as a motorway can be!”

“The greatest work in Scotland”

Engineer Jim McCafferty was thrilled to finish up at university and land a job on the Inner Ring Road project.

He recalled: “It was an eclectic group of people there from various parts of the world, London, Poland, Hong Kong, Nigeria.

“I found it a very exciting environment to be working in. It was jumping. Everyone was full of enthusiasm for the whole idea of the motorway system.

“In the railway era, Isambard Kingdom Brunel thought he was involved in the greatest work in England. I remember as a young man thinking that I was involved in the greatest work in Scotland if not the UK.

“Various people did attempt urban motorways and the like in cities like Birmingham and Coventry and so on. Almost all of them ended up with a hotch-potch.

“Glasgow actually produced a rather good solution. One of the reasons was because right from the start we worked with the consulting architects, who were involved with the aesthetics.”

Jim remembers questions being asked of the merits of effectively wedging through the city with a bustling motorway.

“Eventually, I think especially in the Charing Cross area, people began to ask questions about how much more of Glasgow was going to be knocked down.

“On top of that there was an oil crisis, where the price of oil shot up and certain people produced figures predicting that the increase in traffic was all going to plummet and no-one would need a motorway system.

“It’s amazing how the predictions from the Highway Plan have been borne out in practice. The growth in traffic has been very realistic, if you take into account various things that impact on it.

“If you look at things like pollution levels, accident deaths, they’ve plummeted. The number of people being killed on Glasgow’s roads was pretty large in the 1940s, 50s and 60s. The amount of pollution was huge.

“Apart from all the new roads and structures and so on, we ended up with Gordon Street, Buchanan Street and Sauchiehall Street and others pedestrianised, which was a great boon. These were all areas where there were huge amounts of traffic arriving in Glasgow.”

Jim says he “thoroughly enjoyed” the experience of working on the ring road project.

He added: “I thought that we had done a good job and then, once the motorway beyond the bridge to Ibrox was finished, I was invited to join the firm in Hong Kong.

“I took with me the expertise that I gleamed in Glasgow. It’s one of these places where they have preserved certain parts, but it’s a bustling modern city full of skyscrapers, massive bridges, roads and motorways. But it’s remarkably beautiful.”

Jim would later be involved in the major refurbishment work on the bridge, which was awarded the Saltire Award for civil engineering excellence in 2001.

“We had to investigate what exactly was wrong and what was to be done,” he recalled. “The study resulted in a need to strengthen the bridge at midspan and basically lift the two parallel viaducts and move them a little way towards the south, to relocate them to where they should have been.

“This was a very delicate operation, with the columns that were holding the bridge up encased in new columns all the way round, and the bridges jacked up and resupported on these.

“The old columns had to be severed top and bottom and slid out horizontally. The new columns were filled up with concrete and the bridge transferred onto them.

“This was one of the biggest bridge lifts ever attempted anywhere.”

For more on the history of Scott Wilson Scotland, visit scottwilsonscotlandhistory.co.uk

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe © Glasgow Motorway Archive

© Glasgow Motorway Archive © Glasgow Motorway Archive

© Glasgow Motorway Archive © Scott Wilson History

© Scott Wilson History

© Glasgow Motorway Archive

© Glasgow Motorway Archive © Scott Wilson History

© Scott Wilson History © Glasgow Motorway Archive

© Glasgow Motorway Archive © Scott Wilson History

© Scott Wilson History © Scott Wilson History

© Scott Wilson History