When James Bond was pitted against his Cold War enemies he did so with an Aston Martin, deadly gadgets and, given his penchant for Martinis and five-star hotels, seemingly unlimited use of the MI6 credit card.

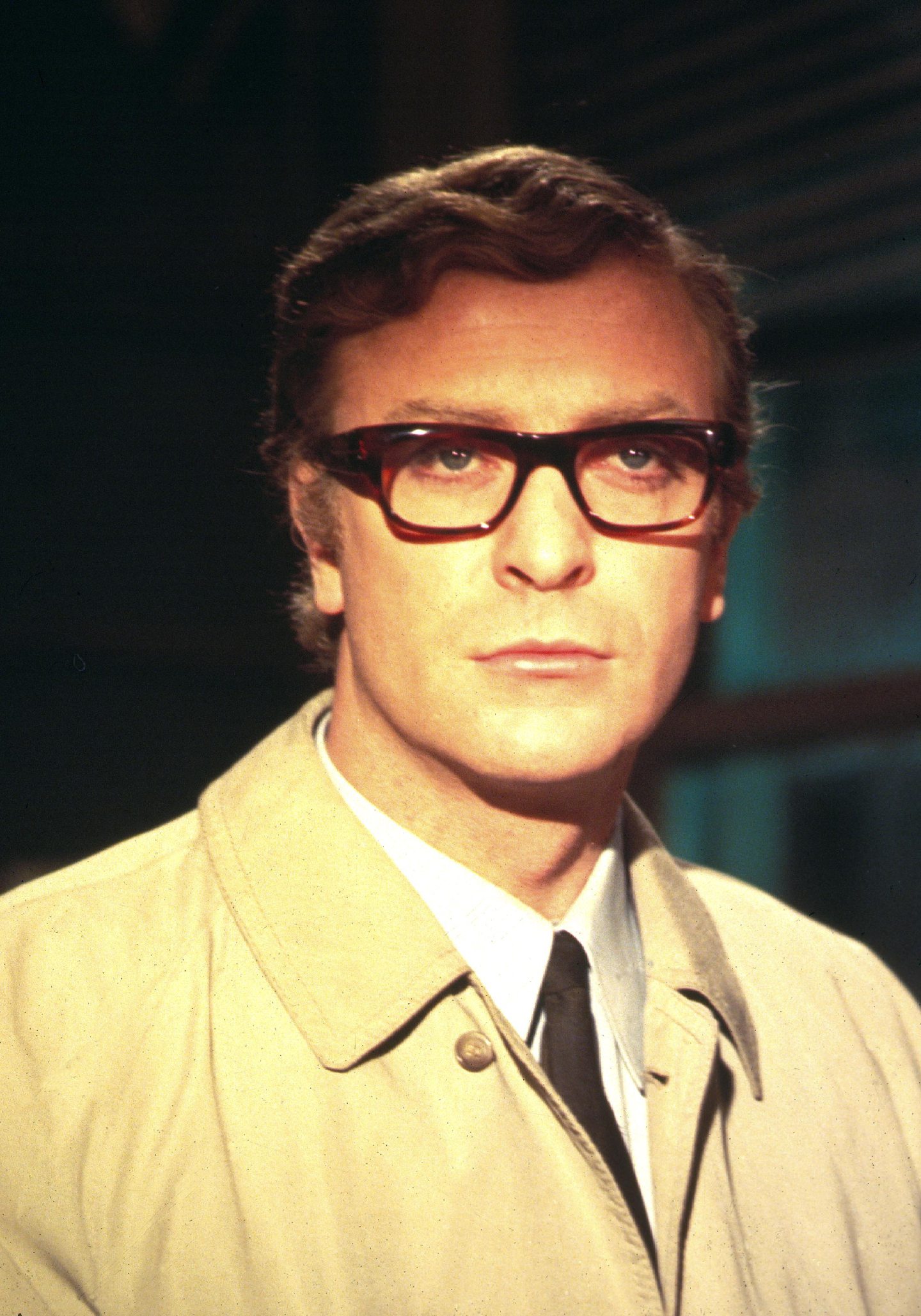

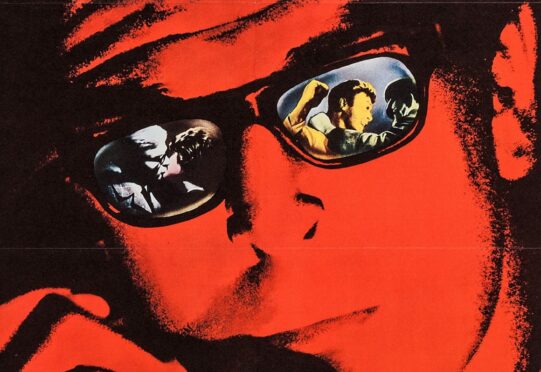

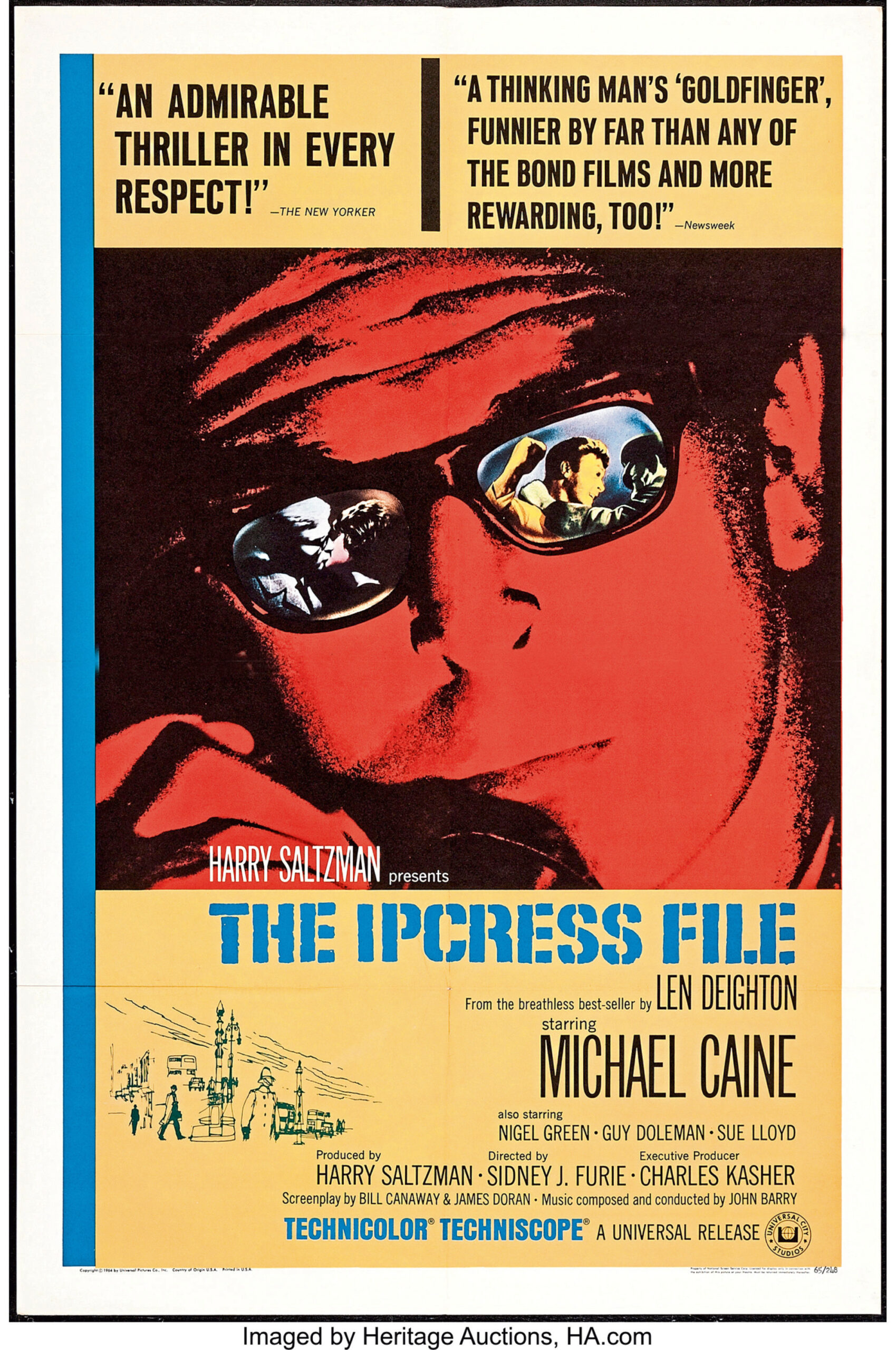

Fellow ’60s spook Harry Palmer, meanwhile, took on the might of the KGB armed mainly with his Cockney wits and a pair of chunky acetate NHS specs. The lead character of novel The Ipcress File has been described as “the kitchen sink Bond”. Palmer, played by Michael Caine in the 1965 adaptation and its sequels, spent more time wrestling with tiresome red tape than with Soviet henchmen.

The series’ tone, its protagonist and even its success was milder than the flashy Bond movies, yet the appeal of its thoughtful, bespectacled hero endures. A new TV adaptation of The Ipcress File is coming to ITV next month, starring Peaky Blinders’ Joe Cole, and according to its writer John Hodge, the man who adapted the Trainspotting movies from Irvine Welsh’s novels, Palmer is in a class of his own.

Hodge first read The Ipcress File after spotting its iconic cover, rendered in shades of grey, with a cigarette butt crushed beside an espresso cup, some paperclips and a revolver.

“When I first read it, here was this character going to the delicatessen to buy sausages, and how his commanding officer in the army didn’t really like him because they were from different social classes,” says Hodge. “And there was humour and wit in everything.

“I read the book again 10 years later and understood it more. What Deighton drew was a working-class guy exploring this new world of the early 1960s: air travel, food from other countries, increasing social mobility. He’s all those things, not just a guy determined to defeat the KGB.”

Over the course of 27 movies Bond would rather brood or seduce a femme fatale than question why he was doing what he was doing. Meanwhile working-class Palmer, according to Hodge, is a man divided as much as the world separated by the Iron Curtain of the 1960s.

“He’s a reluctant spy, one torn by two inclinations,” adds Hodge. “One is to get through life looking after himself, with as little grief as possible: he’s trying to make a comfortable life with one eye open for opportunities.

“But I think there’s also a strand of his personality which he doesn’t recognise in himself. He has a sort of fundamental belief in the kind of Western way of life. Democracy and personal freedom and all that, but he would never make a big speech about it.

“He’s not sadistic at all and doesn’t take pleasure in others’ defeat or injury. He’s not a rabid anti-communist either. He’s more of a pragmatist.

“At the same time he’s not blind to his own flaws. He would never say this, but he wants to do the right thing for people, and has a quiet humanity. He’s a decent human being in a complex world.”

Returning to the paranoid nitty-gritty of 60 years ago, by depressing coincidence, has been apposite given Nato’s current standoff with Russia over Ukraine.

“It’s 2022 right now but with forces of East and West literally facing each other across a border it could be 1962,” says Hodge, a Glaswegian living in Bath. “As well as being kind of sad we’re still there, so it’s also terrifying.

“In 1962, with the Cuban Missile Crisis, that terror is what people lived with, too. Yet in the same way we’re sitting talking about a television show now, people in 1962 were just getting on with their lives: listening to jazz records or reading about The Beatles or buying sausages from the delicatessen.”

Caine brought working-class charm to the role of Palmer (in the book, the character was unnamed) in the 1965 adaptation of The Ipcress File, directed by Sidney J Furie. Adding a touch of swagger to the latest adaption is 33-year-old Joe Cole.

“He’s got charisma and swagger but I also think he’s likeable,” says Hodge. “That’s a great thing, and the right thing for Harry Palmer. There’s something, in the best possible way, ordinary, about him.

“He’s not a superhero, he’s a decent, good man navigating a complex moral world. That’s tough for an actor to deliver and Joe does that.”

At one point in The Ipcress File, a senior policeman tells Palmer a relative works at the same agency where he’s been drafted.

“You people all know each other, don’t you?” says Palmer, knowingly and in a way a privately-educated intelligence officer wouldn’t even notice.

“I think that’s the key to it,” says Hodge. “Harry finds himself in this world where everyone in power seems connected.

“It feels to Harry that he’s up against this self-supporting network and he feels on his own.”

Characters have been either expanded or created for this new adaptation, including a black CIA officer Maddox, played by Ashley Thomas.

Maddox was based on Leutrell Osborne’s memoir, Black Man In The CIA, which details how the author became one of the agency’s first black case officers in 1957.

Hodge, 57, wrote 1994 thriller Shallow Grave before adapting Trainspotting in 1996; both were directed by Danny Boyle. He again worked with Boyle on The Beach and A Life Less Ordinary before reuniting again in 2017 for Trainspotting sequel T2.

“If you look back it seems like both yesterday and 100 years ago at the same time,” he says. “It’s very weird. Making that sequel was a lovely experience. Working with all those people again, Danny Boyle, Andrew [Macdonald, the producer]. I’ve worked with them separately down the years but to work with them, the actors and the crew again was fantastic.

“It gave me a real appreciation of the original film which I hadn’t watched in a long time. I watched it a lot of times in 1995-96 then I deliberately stayed away until we made T2.

“It was over-familiarity. It was nice to see it again and remember things I’d forgotten. You see it all in a fresh light. That opening 60 seconds is just amazing.”

The movie helped launch the careers of Kelly Macdonald, Robert Carlyle, Ewen Bremner, Jonny Lee Miller and, of course, Ewan McGregor.

One of Hodge’s lines in the script is memorably delivered by McGregor’s character Renton, post coitus: “I haven’t felt that good since Archie Gemmill scored against Holland in 1978!”

“I feel really pleased with that bit!” said Hodge, laughing. “Kids today probably won’t remember 1978 but for a generation that was a seminal moment of national elation and disappointment.”

Although he’s written his own screenplays before, Hodge seems to be more at home adapting other works, and views Len Deighton’s sequels, rather than his own spin on the character, as potential for Cole to return as Palmer.

“I feel more secure. I feel more comfortable basing it on something that’s pre-existing,” he adds, thoughtfully. “I don’t know. It feels truer to the source material to do that. I wouldn’t like to hijack the character, as it were.

“There’s quite a lot of invention in our adaptation, just out of necessity. I would hope Len Deighton watches it and hope he feels it’s close to the spirit of his novel.

“If I was taking it further, I would always want to base it on one of the novels. Billion Dollar Brain, Funeral In Berlin and Horse Underwater are great novels so there’s more there if someone wants to do it.”

Thrills and grills: How best-selling author had secret life in the kitchen

Deighton, now 93, wrote a total of five cookery books, 27 fiction novels, and military history books on topics including The Battle of Britain.

As a thriller writer, Len Deighton was one of Britain’s best but the author was also no slouch in the kitchen.

And he was happy to give Michael Caine some culinary tips before a famous scene in The Ipcress File when Harry Palmer prepares an omelette, deftly cracking the eggs with one hand.

However, all the close-up cooking was done by Deighton. The decision, although made out of necessity, was appropriate, as Caine wasn’t the first ’60s bachelor Deighton taught to cook.

In addition to his fiction writing, he was also the food correspondent for The Observer newspaper, creating weekly “cookstrips”, which were designed to be “man-friendly” in an age when husbands rarely even entered the kitchen.

The simple instructions, illustrated with line drawings, were inspired by Deighton’s own shorthand, which he developed as a student working in hotels and restaurants in London and Paris.

“I was buying expensive cookbooks,” he explained in a 2014 interview with The Observer. “I’m very messy, and didn’t want to take them into the kitchen. So, I wrote out the recipes on paper, and it was easier for me to draw three eggs than write ‘three eggs’. So, I drew three eggs, then put in an arrow. For me it was a natural way

to work.”

The series, which ran from 1962 until 1966 – clippings of which can also be seen in the background of the The Ipcress File scene – were later collated in two bestselling books, Action Cook Book and Où Est Le Garlic?, cementing Deighton’s position as Ian Fleming meets Fanny Craddock.

Deighton added: “Generally, you stand a better chance of succeeding in something if whatever you create, you also like to consume. I’ve never written books for people more clever than I am, or more stupid than I am. I’ve always tried to direct things at people like me. Whatever I was cooking, that’s what went into the cookstrips.”

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe