When Stuart Campbell first stepped on to the wards at Queen Mother’s Hospital, he was just 18 years old, fresh-faced and eager to learn.

Working as a trainee obstetrician, he wanted to soak up knowledge, and quickly realised he was in the right place.

His mentor, Dr Ian Donald, had been instrumental in the invention of one of the world’s first ultrasound machines, the Diasonograph. And it was in this small hospital department in Glasgow that the very first images of foetuses in utero were captured – and where Dr Campbell began research that would forever change the way we monitor and care for babies in the womb.

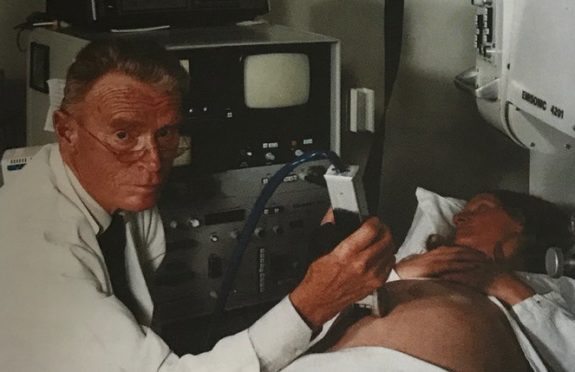

“I was a junior doctor in Ian Donald’s department in 1965, and I used to see him down in his darkened room, scanning pregnant women with this huge machine,” explained Dr Campbell, now 83, whose career is detailed in The First Breath.

“He did the first early diagnosis in obstetrics and captured the first pictures of a baby’s head, which were very crude and fuzzy. No one seemed very interested in his research – but I was.

“I started to use this big machine, which filled about a third the room, to look at the baby’s head and take a very accurate measurement.

“I would get ladies to come up early on a Sunday morning. It was kind of like their new religion.

“There is nobody better than a Glasgow woman. They were so co-operative, so friendly and very supportive of a young doctor trying to make his way in a growing field.

“I would measure their baby’s head every week and develop charts for their growth, and eventually I found I could predict the age of the baby based on these early measurements.”

Publishing journals and papers on his findings, Dr Campbell’s work pioneered the use of foetal measurements to estimate age, size and weight, something which is now crucial for monitoring a baby’s development.

After moving to London, he went on to use ultrasound to diagnose foetal abnormalities and identify high-risk pregnancies, and later established the first foetal medicine department in the world at King’s College Hospital.

Now working in reproductive medicine, Dr Campbell argues Scots have always been at the forefront of obstetrics and foetal medicine – but is modest about his own efforts.

Dr Campbell explained: “Scots have made huge contributions to the world of medicine, especially obstretics. There were the Hunter brothers, William and John, who developed modern obstetrics in the 18th Century, and William Smellie, working in the 1700s, wrote the textbook on how to deliver a baby and made childbirth much more scientific and safer for women.

“The use of chloroform anaesthetic for childbirth and Caesarean sections was also pioneered by Sir James Young Simpson, from Edinburgh. And my own mentor, Ian Donald, was a gigantic figure in our field.

“Personally, I am just honoured to have been able to continue some of the brilliant developments that were made in Glasgow in the late 1960s and early 1970s.”

Looking back over decades of advancements and change, Dr Campbell says medical technology will only continue to improve, especially in the field of IVF and genetics.

He said: “There will always be a few anomalies and developmental abnormalities that are untreatable and which even an operation won’t help.

“But we can give hope to parents now thanks to scientific improvements.

“We probably won’t be able to cure every problem, but we’re going to continue to make big advances.

“In terms of gene defects, there will be more and more genetic engineering in the future.

“I work in IVF now, and I believe we will be able to engineer an embryo to remove abnormal genes from women that have genetic diseases.

“It’s controversial, but it will happen – I’m absolutely certain. And I think it will be quite soon.

“We already have a virus we can insert into the genome to and correct the abnormal gene, and there are doctors in China who have modified genes.

“IVF itself was opposed by many people, and it took a long time for the ethical objections to be put aside, but if parents want their baby to be treated, it will happen.”

If my son had been born when I was he wouldn’t have had the chance to survive – Journalist Olivia Gordon

Staring at a grainy black and white image, while the sound of tiny, pulsing heartbeats fills the room, an ultrasound appointment is the first time most parents meet their new baby.

But seeing those first squiggly lines and blotchy dots can mark more than just the start of parenthood – for some, this everyday procedure can turn a moment of joy and hope into months of fear and uncertainty.

This was the experience for journalist Olivia Gordon, 40, who discovered during a routine 29-week scan that her baby boy had just a 50% chance of survival.

Olivia, and husband Phil, learned their baby was critically ill with hydrops fetalis, a rare condition that causes the body’s lymphatic system to fail.

Amniotic fluid was building up in Olivia’s womb, crushing her baby’s lungs, restricting growth and increasing the risk of premature birth.

“When something goes wrong with pregnancy a lot of people worry it’s something they did,” explained Olivia, who had previously suffered a miscarriage.

“I was paranoid all the way through my pregnancy about doing everything by the book. I was scared of something going wrong again.

“I didn’t necessarily feel guilty, but I didn’t feel like a proper pregnant woman. I felt like I had somehow failed or my body wasn’t capable.”

To save her baby’s life, a sharp, thick needle was pierced through Olivia’s stomach, placing a coiled plastic tube, or “shunt”, halfway into the his chest wall, draining the fluid.

The risky in utero procedure was a success, but the baby was delivered prematurely at 32 weeks. But after five anxious months of neonatal care, baby Joel came home.

Now, eight years on, Olivia has written about her experience in her book, The First Breath: How Modern Medicine Saves The Most Fragile Lives.

As well as sharing the story of how her own tiny “miracle baby” came into the world, the part-memoir, part-popular science book explores the history of foetal and neonatal medicine.

She said: “ The book is really my attempt to explore and understanding how this area of medicine has developed.”

Revisiting the units and doctors that saved her son, Olivia shines a light on what happens when pregnancy doesn’t go as planned.

“If my son had been born when I was, he wouldn’t have had the chance to survive. That’s mind-blowing, really.

“There has been so much generational change. Women giving birth now will have a totally different experience to their mothers or grandmothers. It’s all happening so quickly.”

The First Breath by Olivia Gordon is out now, Bluebird, £16.99

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe