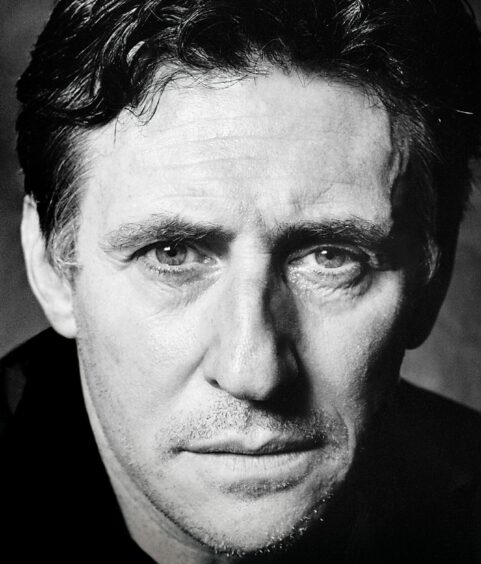

Gabriel Byrne sighs at the thought of being typecast as a moody heartthrob, albeit in a quite moody way.

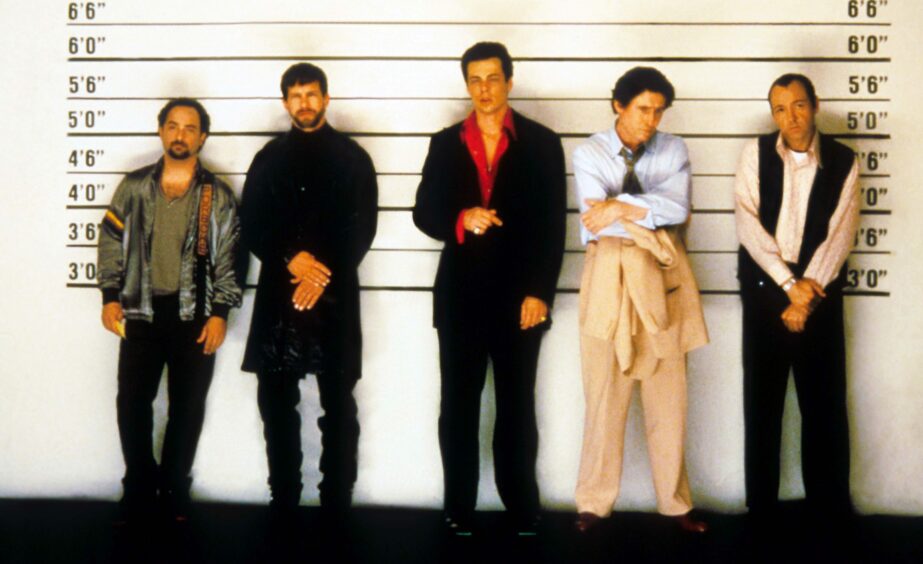

Despite an aversion to being described as brooding, his brand of thoughtful intensity is a seam running through his long and acclaimed career: from his first role in Excalibur, to cult classics such as Miller’s Crossing and The Usual Suspects.

But, as he explains the ambitions he still harbours at 72, he seems keener for less tortured introspection and a little more slapstick.

“I suppose if I want to do anything from now on, it would be to do more comedy,” he says during a Zoom call from his US home in Maine.

“When I started my career in the theatre it was in comic roles. Then I got cast in Excalibur, which was a serious film, and Miller’s Crossing. People said: ‘Oh, he’s a serious actor’. That happens very quickly.

“So nobody’s ever asked me to do comedy. Last week Bernard Cribbins died, a great hero of mine because he was funny but he also had a great compassion as a performer, a real depth and sensitivity.

“He could do Chekov on stage then be in a comedy like Two Way Stretch. That to me was a beautiful career.”

Byrne lights up with enthusiasm for the comedy of Peter Sellers, Adam Sandler and French silent movie star Jacques Tati, who inspired Rowan Atkinson’s recent family comedy Man Vs Bee.

“With Jacques Tati, I’d urge people to watch Monsieur Hulot’s Holiday,” he smiles. “He was a genius because, through the art of silent comedy, he was able to make comments on things like noise, traffic, corporations, dress, manners and social convention. And he did it with very, very few words.”

Later this month, Byrne is coming to Edinburgh to perform the one-man stage show of his celebrated evocative memoir Walking With Ghosts. In it, his story moves from the “street theatre” of a working-class Dublin suburb, to the real theatre via acting, then television and Hollywood stardom. Amid the story of his life, he speaks of a sexual assault at the hands of a Christian Brother as a boy, as well as his battle with alcoholism, and panic attacks while on the brink of stardom in Cannes.

There’s also his winding career path which led him to briefly become a labourer, toilet attendant, plumber and even, briefly, a stint in a seminary. At times powerful and poetic, Byrne also peppers his recollections with wry Dublin wit and, at times, Tati-like physical comedy.

The stage where he started might seem like a natural home but in Walking With Ghosts Byrne speaks of the stage fright he still feels moments before curtains up; which he reckons he’ll still feel when he appears at Edinburgh’s Kings Theatre.

After 40 years of treading the boards, you’d imagine he’d have some methods to defeat it. He delivers a pause and a sigh at the thought of it.

“I don’t know the answer to that,” he says. “Honestly, I don’t know. It’s so contradictory. If someone asked me at a party to sing a song I’d melt. If someone points me out in public, I freeze.

“On stage, you walk out in front of a bunch of strangers with some lines in your head.

“Put it this way: if you see footballers in the tunnel before a game and they’re jumping up and down, I know exactly what they’re feeling inside.

“Part of the game is to come out and pretend you’re not nervous, but you are. You can’t give it away because if you do they lose confidence in you. You can’t show that fear. The audience can be a bit like a dangerous dog.

“I’ll try to ignore the audience, in the best possible way. I want to say to them I’m here to do this, and it’s for you. You have to adopt that attitude, otherwise you’ll go crazy.”

Fame made an attempt to dislodge Byrne’s sanity in 1995, following the premiere of the role for which he is perhaps best known, as Keaton in The Usual Suspects.

It was there, in a French movie theatre, surrounded with industry types clamouring for a piece of him, where he had his first panic attack.

“I walked into a room and knew a couple of people,” he recalls. “Three hours after the film, people were four or five deep around me, desperately trying to give me phone numbers. I thought, ‘I don’t want to be doing this’.

“I couldn’t trust these people, they were telling me these things they don’t believe. How could I believe it?

“All that rattles your identity. It doesn’t mean anything, it doesn’t mean you’ve achieved anything; the only thing that does that is if you do good work.

“It doesn’t matter what critics say. If you say to yourself you did the best you could, that’s the satisfaction, that’s as good as it gets. The same applies to your life.”

Byrne wants to remain private while, at the same time, sharing the details of his life. He declines questions about abuse or alcoholism, yet talks about them in his book and on stage. The incessant questions, the attention and the insincerity are downsides of a fame in which he’s not especially interested.

“There are people in the business who love that kind of attention, I’ve worked with a few like that, and there are people who want to worship at that shrine, as spectators,” he adds. “I’ve never felt comfortable with that, it makes me cringe.

“I hate the objectification of women, I hate playing that game. I’ve seen what it does to friends of mine. And girlfriends who had to spend eight hours getting into dresses, getting their hair and lipstick done, just to be on the red carpet.”

He shakes his head at the thought of the circus that goes with it all.

The trend for movie stars these days is to front a series for a streaming giant, yet Byrne believes these platforms, and modern movies, have ultimately been disappointing for the art form.

He begins to gesture passionately, a hand with a chunky silver Claddagh ring dancing in front of his face, as he sermonises about the state of movies and television.

“They need so much content so how can they keep any consistency of standard? It goes out and it’s forgotten in a week,” he says. “You have 500 channels where the audience can hop, and that ties in with the idea there’s a general cultural attention deficit disorder that’s happening.

“TikToks are 45 seconds long, now Netflix, Amazon Prime and even cinema movies are being edited in line with people’s attention spans. They think audiences won’t hang around for the emotion of the scene.

“The emphasis now is on spectacle, sensation, then moving on. It’s the diminishing of emotion, story and character. That’s where the stage retains its integrity in a way. When you walk on to a stage you can’t ask to stop and do it again; and the audience knows it’s alive.

“The stage has remained unchanged, in terms of the experience for the audience, since the Greeks, even before the Greeks. That’s why it’s to be valued.”

In Walking With Ghosts, Byrne says a recurring theme is the what ifs? we experience; and how the consequences of a lifetime of decisions only comes into focus as we age. For him, you feel there are perhaps more questions than answers.

“All our lives, no matter who we are, have the same kind of trajectory,” he says. “As Beckett said, ‘Birth was the death of me…’

“We go from birth to death. The externals of my life might be different, but we all share the same themes: of love, life, health, regret, loss, death, and joy.

“They’re all there in this one-and-a-half hour. And the idea is to provoke the audience, like all good drama, into an examination of their own life.

“What would have happened had I not done that? What would have happened if I did? If I hadn’t married that person? If I emigrated? What would have happened if I’d stayed?

“How did I get on with my parents? My parents have passed away, did I get to know them as well as I could? Did they get to know me?”

A decision to get into acting at an older age led Byrne to where he is now: success as an actor, and living in New England with his wife since 2014, Hannah Beth King, 47, with whom he has a five-year-old daughter.

What if he hadn’t decided to conquer his stage fright, though?

“Oh I’d be a retired plumber, living in Dublin. I’d be down the pub betting on the greyhounds and watching out for the Man United score. And of course, the Celtic score.”

Byrne’s first experience of acting abroad was in Edinburgh, when he teamed with director Jim Sheridan to bring a series of William Butler Yeats plays to the Richard Demarco Gallery.

He grins at the memory, recalling passionately trying to get the five people in the audience to care about Yeats while a thumping Elvis Costello And The Attractions set went on in the venue next door.

At 72 his passion, he admitted, isn’t what it was.

“But passion and energy changes as you age. You look back to when you were young and ask yourself why you were passionate about a certain thing. I was passionate about football. I used to support Manchester United when I was growing up, I’d obsessively follow them.

“I’m not passionate about reading now, I’ll still do it but the same passion isn’t there. I’m not burning to do anything that I feel if I didn’t my life would be the lesser for it.

“I’m excited to do certain things, like this show, and visiting Edinburgh. I hope I never lose that sort of excitement.”

Getting drunk with my hero, Richard Burton

Early in his career Gabriel Byrne worked with Richard Burton on the 1983 TV series Wagner.

In this extract from his memoir, he recalls how the legendary actor and hellraiser took him under his wing during filming in Venice.

Suddenly a rogue wave rolled under the boat. The swell unbalanced the make-up artist, and the blade of her scissors went through my lip. Within moments blood was dripping on to my starched white shirt.

“Jesus H Christ! Get them up here! Get the nurse!” shouted the megaphone. I was led ignominiously up the gangplank. The nurse applied iodine and a bandage and I was dismissed for the day.

I returned to my suite and attacked the minibar again, although it was still midmorning. I watched Brief Encounter, dubbed in Italian, and sucked brandy through a straw, my lip throbbing. Sometime that evening the phone awoke me from my coma.

“Hello, Lippy,” said Burton. “Come and have a drink.”

We sat on his terrace, me with my bandaged lip, drinking late into the evening until I felt at ease and drunk again, realising that the shame of a split lip was nothing when you thought about it, especially if it meant you could spend time in the company of your hero, his voice directed at you alone. One of the world’s greatest actors. I’d been watching his performances in the picture houses of Dublin for years, and now here I was getting drunk with him. I remarked on the chaos of the photographers that morning.

“Fame,” Burton said, “doesn’t change who you are, it changes others. It is a sweet poison you drink of first in eager gulps. Then you come to loathe it.

“I’m rather ashamed to be an actor sometimes. I’ve done the most appalling s**t for money.”

“I detest the self mirrored back to me by others. It’s a kind of fractured reality. I can’t see me.

“But this Jameson’s makes sense of everything, for the moment. And poetry, the sound and music of words sooth me, always have. And books.

“Home is where the books are,” he said.

“What I’ve always rather wanted was to be a writer, perhaps it’s too late now.”

“I am at an age,” he said quietly, “when I fear dying in a hotel room on a film.

“Give it all you’ve got but never forget it’s just a bloody movie, that’s all it is. We’re not curing cancer. Remember.”

I’ve made eighty films since then and never forgotten those words

He didn’t die in a hotel room but at home in bed, halfway through a volume of the Elizabethan poets.

Extracted from Walking With Ghosts by Gabriel Byrne, published by Picador. The show is at the Edinburgh International Festival from August 24-28, eif.co.uk

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe

© PA

© PA

© 20th Century Fox/Kobal/Shutterst

© 20th Century Fox/Kobal/Shutterst