In a year to forget, Maggie O’Farrell has had a year to remember as the novelist picked up awards for a book critics are lining up to hail as one of the books of 2020.

Hamnet, inspired by the death at age 11 of Shakespeare’s only son, was published as the lockdown shuttered the country in March and won immediate acclaim and, soon, awards.

But O’Farrell’s head is resolutely not for turning. On the day The Sunday Post catches up with her, all but one of her family are suffering tummy bugs and she is tackling the fallout with gusto and good humour. Clutching a phone in one hand and her cleaning kit in the other, the mum of three reveals: “We have stomach infections. Let’s just say we have the mop out.”

The 48-year-old, based in Edinburgh, born in Northern Ireland, has endured worse. She almost died in childhood after contracting encephalitis. As an adult, she was lucky to escape separate encounters with a murderer and a machete-wielding robber. She suffered a haemorrhage in childbirth, her son – her oldest child, now 17 – contracted potentially lethal meningitis, and her youngest daughter, now eight, came close to drowning.

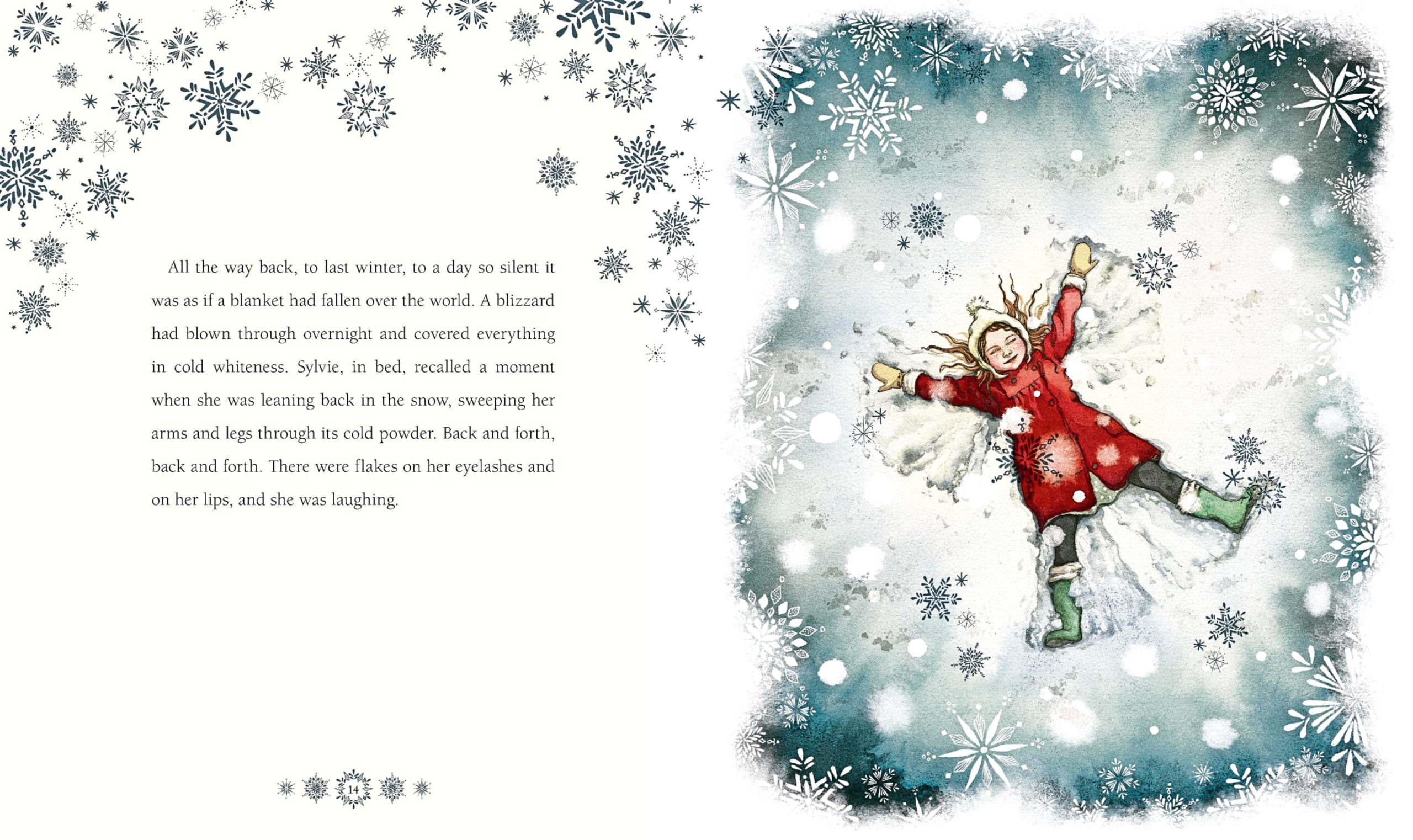

She detailed her family’s trials and endurance in a 2017 memoir, I Am, I Am, I Am – longlisted for the Wellcome Book Prize – and now an ambulance journey to hospital after her eldest daughter, 11, suffered a terrifying anaphylactic shock has inspired a children’s book, Where Snow Angels Go.

O’Farrell, who won the Women’s Prize For Fiction for Hamnet, explains: “It was one of the stories I made up for my children over the years, but the character sprang from an ambulance journey to hospital.

“One of the lesser-known symptoms of anaphylaxis is that you feel suddenly very, very cold. Your heart rate drops. My daughter was freezing and shivering. I told her: ‘It’s OK, you are only cold because there’s a snow angel and he’s wrapping his wings around you!’ Immediately, she was at a distance from what she was experiencing and said: ‘Tell me more’.

“As a parent you are always learning on the job, aren’t you? One of the things I have learned is that if a young child is suffering or in pain, and if you have to explain something to them that is complicated, the only way to do it in a form they can understand is to make a story of it.”

The modern fairytale features a little girl called Sylvie who endures a long sickness and must spend Christmas in bed. On his first visit, the angel alerts Sylvie’s mother to the girl’s high fever; later he summons a wave to pull her out of the sea. Captivated, Sylvie takes risks to see if he will come back.

Other plot points echo O’Farrell’s family experiences. She explains: “When my son was four, he had a low-level virus, but he seemed to be getting better and I had put him to bed.

“For some reason, I woke up at four o’clock in the morning, freezing cold, and thought, ‘I’ll just go and check on my boy’.

“He had a temperature of 42 degrees and a stiff neck. He had meningitis and ended up on an isolation ward. I have often wondered why I woke that night.”

A sea rescue depicted in the book also reflects a real-life incident, this time involving O’Farrell’s youngest child: “She was three and nearly drowned. We were in Spain and I pulled her armbands off and turned around for half a second to get a towel, and she had gone. I saw the ends of her hair vanish into the sea. If I hadn’t seen that…”

How does she cope with it all? “You have to realise that there are people who go through a lot worse. There is always a part of you that wants to think, ‘Poor us, why me?’ but that’s not the way to look at it. You have to think how lucky you are.

“At the hospital I used to go to with my daughter in London, we’d have to walk down this one corridor and we used to be turning right to go to allergies and respiratory medicine. But there was another signpost that went left, and that one was to paediatric oncology.

“If ever I felt really sorry for myself, I used to think, ‘You know what? I am lucky, because when I go to the hospital I turn right and I don’t ever want to be the person who turns left.”

For the last decade, she has been managing the risks of her oldest daughter’s severe allergies. “You have to manage the anxiety and accept the things that are dangerous for her. You have to find the positives in what you have and you have to live the biggest and best life you can in whatever restrictions you have.

“Everybody has restrictions. I say this to my daughter. They may not be as dramatic as anaphylaxis or as visible as chronic eczema, but everybody has something which they struggle with.

“In some ways lockdown was relaxing in that respect because we knew she was at home and home is a completely safe place for her. We were worried that she was going to be a bit more vulnerable to potential Covid infections but her doctors say that as long we keep her asthma under control she isn’t hugely at risk. I haven’t found out if she could have the vaccine early because of her multiple allergies. I’ll just have to wait and see what her doctors say. Everything is a bit up in the air. In 2020 we never know what’s around the corner.”

Of their trials, she adds: “The upside of it all is that it has made all three of my children very compassionate people and has really powered their capacity for empathy. I’d like to think they would be the people to step forward if anyone needed help.

“Any form of suffering can make you empathetic to others and very intuitive of others going through the same thing.”

She felt that keenly while writing Hamnet, which was named the public’s favourite novel of 2020 at the Books Are My Bag awards last month.

“I do cry,” she says. “Especially in the scenes where he dies, and the one when his mother has to lay him out for burial. Those were the most difficult things I have written because you put yourself inside the skin of a woman who sits beside her son’s bed and is forced to watch him die.

“It was really important to me to write those scenes with as much emotional accuracy as I could. I wanted it to be awful, because it would have been awful. Hamnet’s death has always been overlooked and under-written. It is wrapped up in statistics about child mortality in Elizabethan times.

“I’ve read several biographers saying things like, ‘It’s impossible to know how the death affected the family’ and I think, ‘What are you talking about? He was 11, how could it not? He was their child, their only son.”

While Where Snow Angels Go emerged from a traumatic trip to hospital, the seeds of Hamnet were sewn at North Berwick High School where she was taught Shakespeare by an inspirational English teacher, Ewan Henderson.

After publication she sent him a copy. She said: “I told him I wanted him to have it because I didn’t think I could have written it without his lessons. Actually, I don’t think I would have written any books at all without his lessons. He was such a brilliant teacher and I was very lucky to have him. He is retired now. He once gave me full marks for an essay but wrote underneath it, ‘Not bad’.”

In September, Women’s Prize chair of judges Martha Lane Fox announced O’Farrell’s novel as an “exceptional winner”. It beat the third in Hilary Mantel’s Wolf Hall trilogy, The Mirror And The Light, and Bernardine Evaristo’s Booker Prize-winning Girl, Woman, Other to win the £30,000 award.

But O’Farrell reveals: “It was a complete surprise. I was told a day or so before I had to go to the ceremony and give a speech. Normally it would have happened at a party, and I would have been so blind-sided and shocked I would have made a terrible speech. I wouldn’t have been prepared for it at all.”

Does she feel she missed out on the ultimate prize – the Booker, clinched earlier this month by Glasgow-born Douglas Stuart with Shuggie Bain?

Laughing, she says: “Winning the Women’s Prize is a once-in-a-lifetime thing, it’s like finding a crock of gold at the end of the rainbow, so no, I don’t have any sense of being short-changed this year at all. Quite the opposite!”

Where Snow Angels Go, Walker Books

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe © SYSTEM

© SYSTEM © SYSTEM

© SYSTEM