Today, it would have been packaged for television and billed as The Great Italian Paint Off.

In 1504, Florence found its two greatest artists, Leonardo da Vinci and Michelangelo di Lodovico Buonarroti Simoni, in the city at the same time.

Not wanting to waste a rare opportunity for an artistic showdown, government officials commissioned both men to create huge battle scenes in the same council chamber.

The Italians of the 15th and 16th Century obviously loved a public feud as much as we do today and they flocked to watch the artists work face to face for the first time.

It was the culmination of a rivalry that some say lasted throughout their lives but ultimately inspired both to reach even greater heights. It also perfectly illustrates their opposing approaches to art.

As a touring exhibition of Michelangelo’s most famous work, the Sistine Chapel, arrives in Scotland, Martin Gayford, art critic and author of Michelangelo: His Epic Life, told The Sunday Post: “For various reasons on each side, neither of these paintings were ever completed.

“It would have been a very interesting exercise in compare and contrast between them. Leonardo seems to have been all about the fury of battle, the melee of the movements, with lots of dust and confusion. While Michelangelo had a lot of nude men getting out of a river, because there was a myth that the soldiers in the battle had been taken by surprise while cooling off and swimming in open water.”

The passing of four centuries has done nothing to dim our fascination for the artists. Later this month an interactive exhibition, Michelangelo’s Sistine Chapel: The Exhibition, arrives in Glasgow and Poldark’s Aidan Turner is playing da Vinci in glossy historical drama series Leonardo, now showing on Drama.

We often think of the men as peers but their relationship was complicated by professional jealousy and differing approaches to art and life.

Da Vinci’s paintings were rooted in his love for science and nature while Michelangelo was more interested in the perfect beauty of the human body.

Martin Kemp, emeritus professor of art history at the University of Oxford, has written several books on Leonardo da Vinci. He said: “People today ask, was Leonardo da Vinci a scientist or an artist, or both? The words mean very different things these days but he would have not seen a division between them. He would say his job was to understand how nature works. He would look at nature incredibly hard whether it’s a human figure, a plant, or the effects of light on the moon, and he would say that it was rational knowledge of nature. To da Vinci, the artist’s job was to use that knowledge of nature to make pictures.

“The Mona Lisa, for example, is not a straight mugshot of Lisa Gherardini. It’s a statement about the body of the woman, about drapery, light, the body of the earth, with the mountains and the lakes in the background. He is using his understanding of nature to reconstruct it.

“He would say that in painting The Last Supper, and the terrible pronouncement of Christ that ‘one of you will betray me’, he is trying to understand how the brain works, how the nerves work, how we respond to something that we hear, how the anatomy of action works, how the perspective of the room works. It’s an almost impossible agenda.

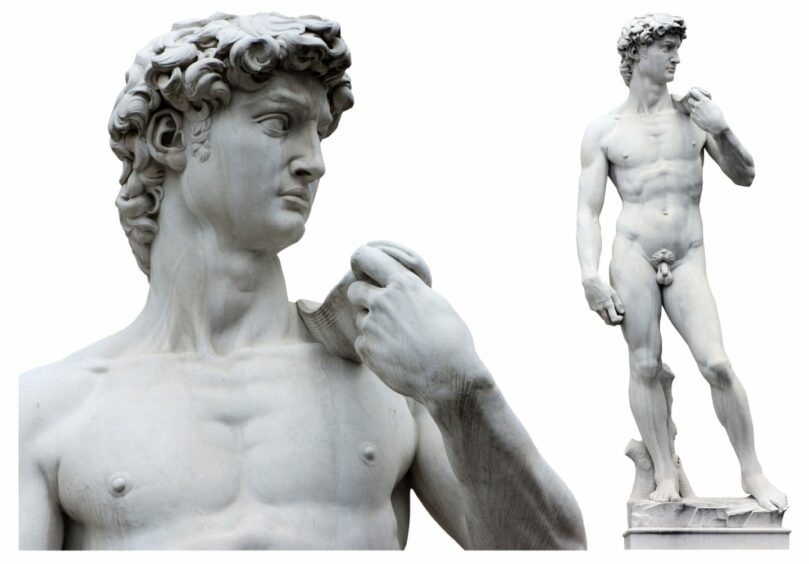

“For Michelangelo though, art was about the soul, and the way you expressed the soul was through the human body. Not through landscape, or drapery, or light and shade. He looked for ideal figures and perfect beauty all of the time.

“His statue of David is ambiguous – where is Goliath in the story? Is David triumphant, or is he gearing up for the battle? By leaving Goliath out, he is inviting us to speculate about what David is thinking. It’s an evocative image.”

The great artists’ personalities were as different from one another as were their styles. Da Vinci was courtly, amiable, well-dressed and popular. When he died, he left behind hundreds of notebooks and papers but hardly anything at all about his inner or private life.

Michelangelo was scruffy, rude and temperamental and often fought and argued with his patrons. Yet he left behind numerous poems, letters and sonnets, full of passion and love for the people he was close to.

Gayford is sympathetic to Michelangelo’s often very difficult ways. He said: “He had tremendously high standards and was a perfectionist. I think if people accepted that and how he wanted to do things, he would be fine. But if he felt you were trying to make him do something that was beneath his standard, there would be fireworks.”

The Sistine Chapel ceiling, painted by Michelangelo between 1508 and 1512, is considered a cornerstone work of High Renaissance art. But the commission, which took five years to complete, tested the artist’s faith in his own talents.

Gayford explained: “According to Michelangelo’s testament and letters, the only thing he considered to be his profession was being a sculptor, particularly a sculptor of stone.

“That was probably why there was a dispute about painting the Sistine Chapel. He didn’t really accept that he was a painter. When he painted the Sistine Chapel he hadn’t really done any other paintings that had been shown in public before. He probably wasn’t tremendously confident about his abilities as a painter at that stage. There was a suggestion that he felt he was being set up to fail by rivals because the ceiling was such an enormous area and it was a difficult surface with a complicated, curving geometry. It is obvious now that he was always going to do a good job but at the time it possibly wasn’t to everyone.”

Despite the two artists’ differences, and their intense personal dislike of one another, each begrudgingly respected the other, and were influenced by their works. Kemp explained: “They clearly respected each other as artists, although they didn’t admit that.

“Leonardo was on the committee to discuss the placement of David, and he made a little sketch of the David as a homage to it. Michelangelo was clearly affected by Leonardo’s Madonna And Child compositions, and his battle scenes, and so on.

“They were chalk and cheese in almost all respects, but they always knew that the other was a formidable artist. That almost made their rivalry worse, in a way.”

Da Vinci star: Discovering fresh perspectives on his life makes me see his art differently too

Poldark star Aidan Turner took on one of his most challenging roles when playing the famously mysterious Leonardo da Vinci in TV drama Leonardo.

“We are trying to get down to what inspired him, what made him tick. I think this story really got to the essence of who he was, emotionally, and what spurred him on creatively. It’s not just historical beats of what he did,” said the Irish actor, who played another famous artist, Dante Gabriel Rossetti, in the 2009 series Desperate Romantics. While much is known of da Vinci’s public life, very little is known about his personal life or relationships.

Historians still debate da Vinci’s sexuality and whether he was, or was not, gay or bisexual. The artist never married, and was once charged with associating with a male prostitute, although the accusation was later dropped due to lack of evidence.

Turner’s Leonardo, streamed on Amazon Prime last year, has romantic relationships with both men and women. Turner was happy to explore this side of Leonardo’s love life.

He said: “I hadn’t seen any depictions of him as homosexual. That’s something we didn’t shy away from. It was nice that it wasn’t questioned. I don’t think many shows have showed him in that light. It was much needed.” To understand who da Vinci was as a man, Turner spent a lot of time reading biographies of the Renaissance star, and by studying his remaining artworks.

Turner explained this helped him build da Vinci’s character in his mind. “Discovering fresh perspectives on his life led me to look at his paintings slightly differently. There’s something almost tortured in some of it. You can see something else and feel something else, something more visceral about it.”

Stunning display to bring the Sistine Chapel to Scotland

We have all gone to a museum or historic monument to see a famed artefact or piece of artwork and have been left feeling, well… a little underwhelmed. It is hard to be swept up in the mastery of a Mona Lisa or a Sistine Chapel when you are craning your head over a huge crowd of people just to catch a glimpse.

That is what the CEO of SEE Global Entertainment Martin Biallas thought anyway. “He went to the Sistine Chapel and didn’t enjoy it,” said Eric Leong, head of operation planning and creative development at Michelangelo’s Sistine Chapel: The Exhibition. “It was packed and he was shoulder to shoulder with tons of other tourists while guards shouted at the crowds not to take pictures and he was rushed out after 20 minutes.”

Biallas had the idea to give Michelangelo his own touring art exhibition where you could get up close and personal with his work without being crowded or rushed.

Also, there is no need to do an Exorcist-style head-spin to look up at the Sistine Chapel ceiling. Huge prints allow the viewer to see up close the intricacies of Michelangelo’s work.

Leong said: “Everyone recognises The Creation of Adam but there is so much more detail and figures that people haven’t had the opportunity to see. I always walk the shows in every city we visit before we open to the public to make sure everything is running OK and I am always surprised by the work, and see some detail that I hadn’t noticed before.”

There has been a flurry of “fine art” experiences touring the world, like the Van Gogh: Alive exhibition that is currently in Edinburgh.

They have been criticised for turning some of our most prized artistic works into cheap gimmicks and mere backdrops for pretty Instagram posts, robbing works of the respect they deserve.

Leong has a different point of view. He said: “I understand the criticism, I do. Ours isn’t projected or moving images. We really wanted to create an ‘exhibition’ experience. Still, we like to see people take selfies and photos.

“You get people out to experience and be inspired by art, it is a good thing. If more people were being inspired by art, or spending more time thinking about or creating their own art, instead of arguing with each other constantly over the political topic of the day, the world would be a better place. That sounds terribly cheesy but it’s true.”

The exhibition arrives in Glasgow on June 21. See sistinechapelexhibit.com/glasgow

A sensory onslaught created by one man. Mind-blowing

Here, our art critic Jan Patience recalls a very crowded visit to the actual Sistine Chapel

In 2014 – which seems a long time ago now – I went to Rome with my husband and two children, then aged 13 and 10.

Like most visitors to the Eternal City, The Sistine Chapel and St Peter’s Basilica were must-sees. Getting in involved booking online and waiting in a long queue which snakes around the walls of The Vatican. Then there is security and all the rest but the whole experience of being inside the Vatican – St Peter’s and the 54 galleries of ancient and surprisingly contemporary art you walk through before reaching the Chapel – is a sensory onslaught.

When we visited, access to the Sistine Chapel was limited to 2,000 people at a time, which seems a lot. It is a lot as it is deceptively small – and noisy.

Notices in multiple languages warn you not to speak, but I remember intermittent shouts from attendants of “Silence” and “No Photo”. It gets quiet, then builds again.

It was a memorable experience. Must people (while not trying to sneak a photo) stand and gaze in wonderment at Michelangelo’s delicate frescoes which are on every available wall of the vaulted space.

My head hurt looking up at the daddy of them all; scenes from the Old Testament beginning with the Creation of the World and ending at the story of Noah and the Flood. The fact one man created this ceiling over four years, from 1508 to 1512, is mind-blowing. I would have stayed longer that day eight years ago but it wasn’t possible as the volume of traffic means visting time is short.

Personally, I’m ready, willing and able to give the Michelangelo exhibition in Glasgow a whirl to enjoy 90 minutes in there, getting up close and interactive with some of the most amazing frescoes ever created.

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe

© Shutterstock / MisterStock

© Shutterstock / MisterStock