Looking out across the woodland surrounding his home, Roy Dennis often scans the skies, treetops and grass hoping to catch a glimpse of his favourite wild creatures – but there’s some animals he won’t see, and probably never will, despite years of trying.

The veteran ornithologist has spent the past six decades helping to reintroduce extinct animals to Scotland, including red kites, osprey, sea eagles and beavers which more often than not disappeared due to human encroachment.

He is considered the country’s pre-eminent conservationist but as he looks back over his varied career the 80-year-old admits his many successes are overshadowed by the knowledge so much more still needs to be done to protect our natural world for our children and grandchildren.

“We’ve really damaged the land, there’s no doubt about it,” said Dennis, speaking from his home near Forres, Moray.

“You can always look back and think things were better, but when I was young the intensification of farming had not taken place. In the 1950s and 60s, the country was full of birds because there was less chemical, intensive farming. Then we entered a period of massive changes in agriculture, and that chemical intensification had a really bad impact on our wildlife.

“Now there’s a greater awareness of that. Children are much better educated, and the younger generation are pretty angry about the state of the world. And quite rightly.”

He added: “The problem is that people assume oxygen is just there, and that water comes out of the tap. But all these things are created by nature, they are part of the natural world. We are a species, just like everything else, and we need to live in a world that’s fit.”

It is this passion to help the next generation that inspired his latest book, Restoring The Wild, which is published next week. Detailing a lifetime’s worth of stories, from the early days of his career in Shetland to the later “never-ending saga” of reintroducing the beaver to our rivers, the hardback work is part memoir and part how-to guide for future rewilding projects, which he believes are key to restoring balance and health to our world.

Dennis uses his archive of diaries, letters, notes and field journals to explore how each rewilding project came to life, as well as the difficulties, stumbling blocks and oppositions that came his way. Frustratingly, the dad of four admits, he became used to hearing the word no. He explained: “Some of the projects, like bringing the red kite back to Scotland, after being exterminated for about 100 years, were really difficult. And many of the difficulties came from my colleagues.

“You think the opposition would come from gamekeepers or the like, but it wasn’t. It was people who thought, ‘Oh I’m not sure that is scientific enough’ or ‘You haven’t quite proven that you can do it that way’, all sorts of ‘what ifs’.

“My attitude was always, ‘Never talk about ‘if’, just say when. We’re going to do it, and when?’

“Some of the projects, like the red squirrel conservation project, took three, four or five years of hitting a brick walls, but never giving up. You have to be determined.”

He added with a laugh: “And, as I say in one place, if someone stops you then leave it for a while, and that person will eventually be promoted, moved on, or maybe even die, and then you can go ahead with your plan.”

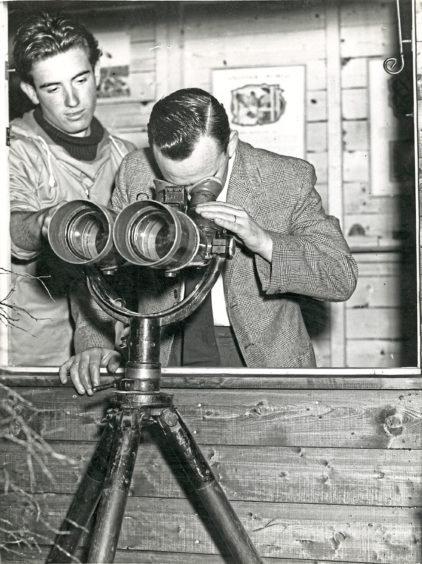

One of the projects he is most proud to relive was also one of his first, the reintroduction of four young Norwegian sea eagles to the shores of Fair Isle, where he was working as warden of the island’s bird observatory in the late 1960s. It was a process that, after months of planning and preparation, successfully brought the majestic birds back from extinction, and became the blueprint for many more successful reintroduction proposals around the country.

While many might assume such rare birds might still only be seen in the wild, Dennis believes successful reintroduction means seeing wildlife everywhere – even above some of the country’s busiest motorways.

“We’ve failed if the only place you can see wildlife is in a nature reserve,” said Dennis, who has lived in the Highlands and islands of Scotland since 1959, when he moved from his childhood home in Hampshire.

“I remember early in my career when I was in Inverness – I used to live in the Black Isle – and an osprey flew over the centre of the town carrying a the fish. I was looking up and I thought, ‘This is so much better than having to go to a nature reserve to see them’.

“The great thing about red kites, too, is that you can even now see them over the M25 when you drive in or out of Heathrow Airport. I just love that. Nature reserves are important, but some of these animals can live in the general countryside, right alongside us.”

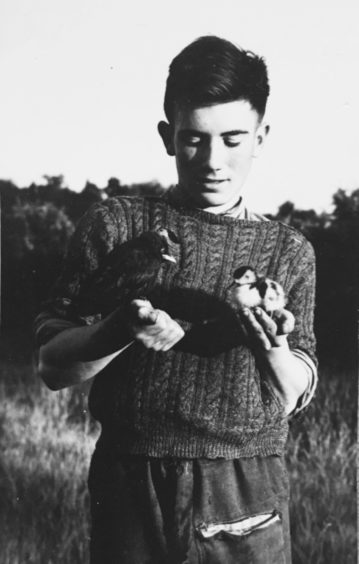

As Dennis talks about his work with seabirds and mammals, it’s clear his job was more than a career. Rewilding and protecting lost species became his greatest passion and today, through the Roy Dennis Wildlife Foundation, he is still advocating for the likes of the lynx and beaver to return.

“I’d love to see the beavers in all rivers, but the beaver situation in Scotland is poor. I don’t like the idea that they can be killed,” explained Dennis, who was the RSPB’s senior officer in northern Scotland from 1970 to 1990.

“I don’t like the government restriction on not allowing them to be restored to all rivers in Scotland. And the politicians blocking that just need to grow up. This animal is so important for restoring rivers, slowing down floods, cleaning effluent that comes off farmland. They’re totally positive animals.

“And the other animal which we’ve tried to do something about for 25 years is the lynx. I’m looking out from my house now, and the lynx could live in the woods just opposite. There’s lots of roe dear and hares, and it would restore, easily, a really important part for the wildlife. The lynx could be here tomorrow but, politically, it’s very difficult.”

He added: “I’d love to see politicians in the next government in Scotland – and I don’t have a political party – be determined to get wildlife back that’s missing, and to rewild or ecologically restore far more of Scotland.

“Scotland is in a very degraded state with so many areas that have lost all their woodland over hundreds of years, and we need to change that.”

From the book

There are always roadblocks but eventually they will be promoted, retire or die and then you must push forward

– Taken from the introduction to Restoring The Wild by Roy Dennis

In 1995 I was invited by Professor Wolf Schröder and Christoph Promberger, large mammal specialists at Munich University, to join them on a summer expedition to the Upper Porcupine River in Canada to study bears and wolves.

In Whitehorse, we met one of their friends at the wildlife division. “Roy has a dream of restoring wolves to the Scottish Highlands,” said Christoph. His response? “Do you work with any other species?”

I told him about my projects on ospreys, eagles and red kites. “That’s good,” he replied. “Because if you work with only one species you will come to a roadblock from a person in authority, maybe even a senior colleague, and then you will have to put your project on the back burner. One day he or she will be promoted, will retire or die – and that may take years. When it happens, you must immediately push forward. So it’s important to have a variety of projects moving at different speeds.”

It turned out to be very pertinent advice.

Looking back now, I realise that great things have happened but I’m disappointed. I’m disappointed that we have not had more success, especially with large mammals. The return of the red kite has been incredible, but this was because of a determined programme of rolling releases from north and south, and the strength of the long-term project team members from the RSPB, Nature Conservancy (and its subsequent national agencies) and enthusiastic individuals and groups. Compare this to the failure, so far, to get the sea eagle breeding again in England and Wales; and the incredible opposition by farmers, politicians and even some conservationists to the return of the lynx.

Yet remember: there’s always change. I think now that if we had really worked hard we could have restored beaver, lynx, crane and eagle owl to Scotland in the 1960s and ’70s. There would have been opposition from some of our colleagues because, in their view, that would not have been “natural”, but in those days there was much less organised opposition from vested interests. A few really enthusiastic people with large landholdings and sufficient funds could have forged new and exciting ecological pathways. I guess our horizons and hopes were not broad enough.

Since that time, the idea of the reintroduction of charismatic species has become more formalised, more difficult and attracted greater opposition, not just from parts of the land-owning, farming, forestry and fisheries communities who see their own interests threatened, but also from individuals and bodies within nature conservation. Guidelines which were intended to help became ever more restrictive and bureaucratic.

One needs to learn, often by painful processes, that the early stages of a bold idea will attract the attention of doubters and opponents to change, as well as supporters. Once a project gets started there is a shift and opposition lessens, and finally – when it is successful – the early naysayers claim ownership. But that matters little to you if your principal aim is to restore nature.

Restoring The Wild: 60 Years Of Rewilding Our Skies, Woods And Waterways is published by William Collins

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe © Shutterstock / Martin Leber

© Shutterstock / Martin Leber

© SYSTEM

© SYSTEM