They are all around and essential to our planet’s survival but, often, we barely give them a second glance.

From coast to countryside, and in towns and cities we take trees for granted, yet they are one of the reasons we exist.

They give us oxygen, store carbon, stabilise our soil, clean our water, nurture our wildlife and provide the tools for shelter, discovery and warmth. But more than that, as the climate change emergency reaches tipping point, trees are a vital weapon in the battle to save our planet.

Now photographer Adrian Houston – whose passion for this precious resource was borne out of happy childhood trips to Glen Coe – is striving to “give trees a voice” and save them from destruction and disease. And he has enlisted a battalion of notable supporters including Joanna Lumley and Alan Titchmarsh to help him.

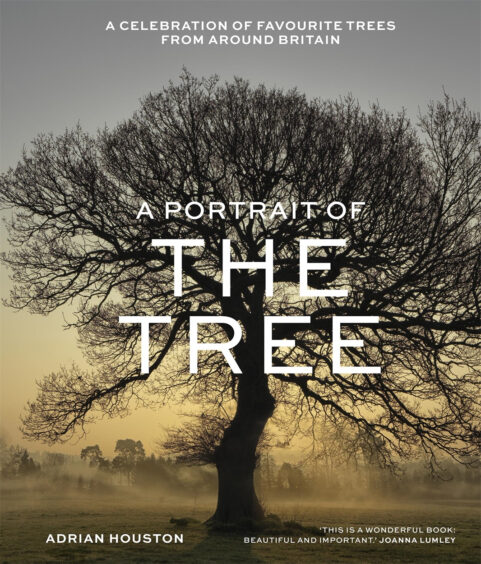

A Portrait of the Tree: A celebration of favourite trees from around Britain is Houston’s new book. Out next month, and packed with captivating photography, it is the glorious culmination of a five-year project featuring scores of trees – some with a history dating back some 1,500 years – and the people who love them.

Among their number is David Knott, curator of living collections at Edinburgh’s Royal Botanic Garden; Absolutely Fabulous actress Lumley; gardening royalty Titchmarsh; and Scotland’s rewilding pioneer Paul Lister, the man behind the Alladale Wilderness Reserve (at Ardgay in the Highlands) and the European Nature Trust.

Houston, now London-based but born in Newton Mearns, Glasgow, to an engineer dad and an artist mum, said: “Nature has an intensity so strong it gives you a totally different view on the world. When you witness Earth’s natural power, it is sometimes hard to see its underlying fragility. Yet scratch beneath the surface and it is there.

“Trees are the longest-living organisms on the planet and one of the Earth’s greatest natural resources. Yet our trees are being affected by deforestation, pollution, global warming and diseases.”

Fundraising for the future

As part of the initiative, Houston has joined forces with Action Oak – a charity initiated by the Prince of Wales and Tony Kirkham, head of The Arboretum at London’s Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew – in a bid to raise awareness and, importantly, cash for research.

He said: “This need to protect what we have, before it is too late, has influenced my work for as long as I can remember. My early connections with trees is from growing up in Scotland and spending time in the forests and on the river banks. When you are walking through the countryside among these incredible huge, old trees, you wonder what they have seen in their lives.

“Glen Coe was always a special location. We spent a lot of time up there; that’s where I caught my first brown trout with my dad and that’s where my favourite Scotch Pine is. The Scots pine is the national tree of Scotland. These ancient trees expanded into Scotland around 8,000 years ago. I have spent many days fishing the high lochs with the Scots pine as my main companion.”

His personal favourite is included in the book, along with choices from the some of the 100 people he approached to take part. “The book was conceived as a way of illustrating how trees connect us all on a universal level,” he said. “A portrait has to capture the atmosphere, beauty, strength and soul in a moment in time. The trees have been chosen by a diverse group of people who all have strong environmental goals.

“Together, they offer a powerful tool to help educate people, from children through to adults about the vital role that trees play in all of our lives, which in turn gives these trees a voice.”

Our favourite trees

David Knott

Curator of Living Collections at Edinburgh’s Royal Botanic Garden chooses the giant redwood

My favourite trees, among the many cultivated within the Living Collection of the Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh, are the Sequoiadendron giganteum, or giant redwoods.

There is a group of small trees in Edinburgh that has been named the John Muir Grove after the Scottish-born environmentalist who pioneered the conservation of wilderness areas in the US, while a number of taller and larger-diameter specimens are at Dawyck Botanic Garden in the Scottish Borders.

At Benmore Botanic Garden there is an avenue of 49 trees planted in 1863, now all more than 50 metres tall, which stretches over 500 metres, creating one of the most impressive entrances to any botanic garden in the world.

This iconic tree now faces a number of challenges: in its native habitat, human settlement has resulted in many groves of the trees being in decline; and in cultivation at Benmore, the impacts of climate change and subtle changes in rainfall patterns, wetter winters and drier springs, now require remedial intervention by the horticultural team to save this iconic avenue and inspire future generations.

Paul Lister

The Alladale Wilderness Reserve, Ardgay, Highlands chooses the Scots pine

Britain is one of the most nature-depleted countries on the planet, a result of our so-called “development”. The Scots pine photographed here has spent more than 400 years growing, clinging to and surviving a steep, scree face on the north face of Glen Alladale. What a life this specimen has had, surviving the logger’s axe; it’s old enough to have seen wolves passing under its branches and marking their territory on its trunk.

Sadly, now too old, this “granny pine” is unable to reproduce, which gave rise to Alladale’s planting programme. We have hopefully inspired other neighbours and landowners to follow suit, in an attempt to help restore what the Romans once called The Great Wood of Caledon. All too often, we humans believe we are apart from nature, but very much to the contrary, we are part of it.

Joanna Lumley

Actress, author, TV producer and environmental activist chooses the London plane

Was it from seeing them when I first came to London, aged eight, and noticed their dappled bark and sweeping branches? Was it when I saw how they spread down their arms to the river, and how their leaves crackle like cornflakes underfoot when they fall?

I cannot remember a time when I didn’t feel in awe of the mighty London plane tree; in parks and along the streets, in palace gardens and on recreation grounds, they tower up to the skies and suck up bad fumes and take care of squirrels and birds. They are giants protecting us while we sleep and shading us when we wake.

They roar in storms and make us sneeze in springtime. Their distant Asian cousin, the chinar, stood over me when I drew my first breath in Kashmir. I hope there will be one nearby when I breathe my last.

From the book

A excerpt from A Portrait of the Tree by Adrian Houston

The world is in the grips of a climate emergency and teetering on the brink of a tipping point when the damage to our planet will be irreversible, according to experts, who say we need to take drastic action, and quickly. One vital resource in the fight against climate change is the world’s trees and woodlands.

Through the process of photosynthesis, trees capture carbon and lock it away within themselves. According to the Woodland Trust, a young wood with mixed species can capture more than 400 tonnes of carbon per hectare.

As well as capturing carbon, trees can also help prevent flooding and soil erosion, reduce temperatures and pollution in urban areas, and support a diverse ecosystem – all part of tackling the impact of climate change.

However, the UK currently has the lowest woodland coverage of any European nation – only 13%. The Woodland Trust estimates that to achieve the UK’s target of reaching carbon neutral by 2050, 1.5 million trees need to be planted. By planting more trees – and protecting our existing woodland – we will also be tackling another environmental crisis: the biodiversity crisis.

A single tree can support a staggering array of wildlife, from small mammals to thousands of different species of invertebrates, from bats and birds to fungi and lichen. Since 1970, 41% of all woodland species in the UK have been in decline, and globally scientists are warning that we are entering the sixth mass extinction.

By increasing woodland coverage, we can support the diverse range of wildlife that thrive there, and help combat this decline.

A Portrait of the Tree by Adrian Houston is published by Greenfinch

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe © Richard Young/Shutterstock

© Richard Young/Shutterstock