It is one of the most remote nations on earth, made up of 32 atolls and one island scattered across the central Pacific, and is home to just 123,223 people. Its nearest neighbour is Fiji, a four-hour flight away, one that runs only on Mondays and Thursdays. Scattered across 2 million square miles, Kiribati is the definition of isolation.

However, that has not stopped the island nation from finding itself at the centre of a superpower struggle for influence in the region of an intensity not seen since the Cold War. It is a struggle that has divided opinion on the islands, across the Pacific and around the world.

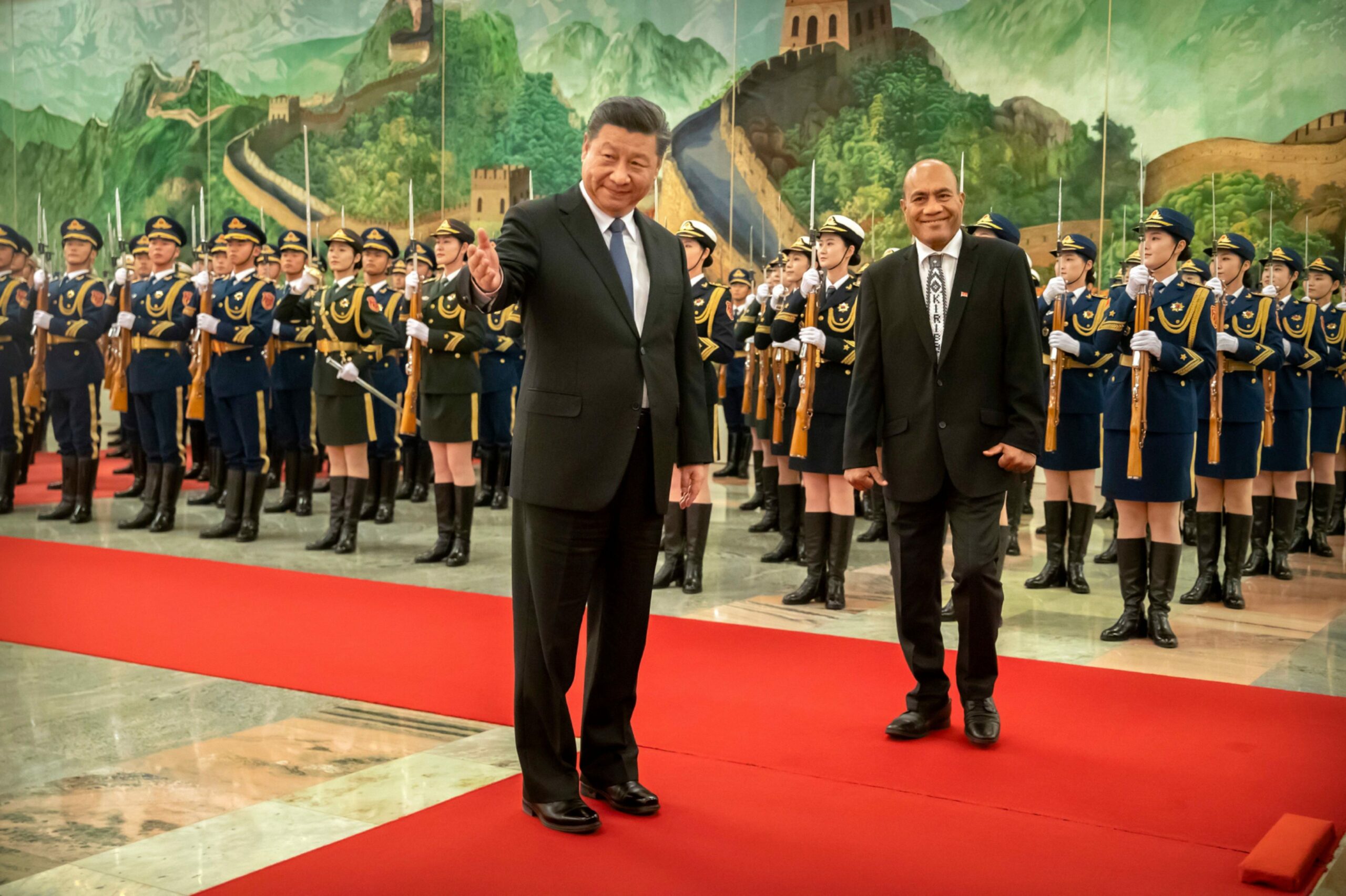

In 2019 Kiribati and China resumed diplomatic ties and Kiribati recognised the One-China principal, which holds that Taiwan, its former partner in development, is not a separate country but is, in fact, part of China.

It is a symbolic gesture but one that is bringing benefits for Kiribati. Last month, it was reported China would renovate an abandoned airstrip on Kanton Island. This sparked speculation that the re-servicing of the airstrip – disused since the Second World War and the Japanese occupation of Kiribati – was for the benefit of Chinese strategic advances in the region. The Kiribati government has refuted these claims, insisting the airstrip is purely for civilian use.

President Taneti Maamau ran on a pro-China campaign that led to Kiribati’s switch in allegiance.

Earlier this month Kiribati withdrew from the Pacific Islands Forum – ostensibly over concerns the interests of it and other tiny island nations were being overlooked but the withdrawal is a blow to Pacific unity, and one that observers fear strengthens China’s hand in the region.

US alarm at this may have prompted its promise to maintain an embassy in every country across the Pacific.

China’s investment in Kiribati follows a pattern it has followed across Africa and Asia, as part of its Belt And Road Initiative. That has seen massive investment in infrastructure projects such as new railways and road links – the “belt” of the title to link previously remote regions rich in natural resources. Meanwhile, the “road” is a series of new maritime trading routes, made possible by building vast port facilities and business parks.

Dr Tess Newton Cain, from Griffith University in Australia and an expert on Pacific geopolitics, said the relationship with Kiribati was progressing exactly as elsewhere. She said: “Investments in critical infrastructure will be the most obvious. Based on what we have seen elsewhere in the region, we can also expect to see an increase in trade and offers of scholarships for i-Kiribati students.”

Key projects including Nigeria’s Abuja-Kaduna railway; the £3.3 billion, Ethiopia to Djibouti route – east Africa’s first electrified railway that reduces a three-day journey to 12 hours; and Sri Lanka’s giant £1.1bn Columbo Port City demonstrate the benefits to the developing world of doing business with Beijing.

Western observers say China’s efforts will give it a worldwide influence in countries thousands of miles from its shores. Cain said: “China portrays itself as a large, developing country and describes its assistance to countries in the Pacific as ‘South-South co-operation’. From the research I have conducted, Chinese assistance has largely been in areas countries such as Australia and the US have not been interested in supporting.”

But there can be a catch. In the case of Zambia, repayments to China’s massive economic aid have run into default after default. Zambia is currently in $17bn of debt, a third of which is owed to China. A nation rich in copper and at the centre of heavy private and public investment from China, there are concerns over the restructuring of the country’s debt.

Meanwhile, Sri Lanka had a complete economic collapse, which earlier this month resulted in the toppling of its government. Analysts have pointed towards the $2bn of debt the country owes China, and Sri Lanka’s role as a partner of China and participation in the Belt And Road Initiative.

Cain said: “Support from China can include concessional loans as well as, or instead of, grants. This can lead to countries carrying a lot of debt to China’s EXIM bank, which can be difficult for them to service.

“So far we have yet to see China do anything that could be considered threatening in relation to a Pacific island country that has been unable to service the debt. Tonga has attempted and failed to have debt forgiven.”

There are concerns in Kiribati that its economic autonomy is under threat. Tessie Lambourne, opposition leader and MP for the island of Abemama, had concerns over China’s role in recent decisions.

“The opening of the Phoenix Islands Protected Area is an example. It’s one of the most fertile tuna fishing grounds in the world,” she said.

In November, it was announced the government would open the World Heritage site to commercial fishing boats. Kiribati relies heavily on the issuing of fishing licences to sustain its economy and China is its key partner in this sector.

However, the decision has left many, including Lambourne, to question the sustainability of this policy: “Opening it to commercial fishing will affect the sustainability of our main economic resource, the backbone of our economy.”

Others remain sceptical towards these claims against China – and contrast them with the behaviour of the UK and US, which used the islands as the location for their atomic weapons testing programme.

Chuck Colbett, a project facilitator at the Malden Project in Kiribati, said: “China has offered to respect our culture and beliefs. Kiribati culture and beliefs were not respected by the UK nor America. The UK has been far from benevolent, reneging on its promise to rehabilitate Banaba.”

As a colony under the British Empire, Kiribati’s island of Banaba was rich in phosphates. Its extraction has rendered the island barren and without opportunity.

“The UK has abandoned Kiribati, boarding up its High Commission,” said Colbett. “China has shown respect towards Kiribati compared to the shocking things the US and UK have committed, ie the atomic test.”

For Colbett and his project, this partnership with China is presented as an opportunity. As a small island nation with limited resources, there is only so much scope for development.

“Hopefully China picks up where the UK left off, with development projects,” he said. “China is the number one in providing tourism, being the main source for the Maldives, Australia and New Zealand. China could also greatly benefit Kiribati with its tourism.”

The group of islands where Tarawa, capital of the Pacific nation of Kiribati, is located, 1,800 miles south-west of Hawaii and 6,000 miles from China.

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe © Mark Schiefelbein/AP/Shutterstoc

© Mark Schiefelbein/AP/Shutterstoc