It ended with a big freeze that brought Britain to a standstill and, after 12 months of frenetic, exhilarating change, perhaps the country appreciated the chance to draw breath.

From politics and civil rights to the environment and pop culture, the world was emerging from two cataclysmic wars, living in the shadow of another, while hurtling into an uncertain but transformed future.

It is a period of turmoil that will soon be examined through the big screen, when Glasgow Film Festival’s retrospective will show 10 movies from 1962 summing up a world on the move.

It was a year, according to experts, that was, with hindsight, pivotal and overshadowed by the Cold War, the chill of atomic weapons instilling dread and dark panic.

“People went to bed wondering if they would wake up in the morning. For many, the world was on a knife edge,” explained Dr Timothy Peacock, a lecturer in modern history at Glasgow University.

“The Cuban missile crisis in October 1962 brought with it the potential that the world’s population could be wiped out by an atom bomb,” she said.

“Here we were, in this period of a need to change and to no longer accept the old ways of life, yet again we were living under the very real threat – at least that is how it felt, even to me as an eight-year-old girl – and on the brink of a third world war, and this would be the worst of them all.

“My parents talked about the atom bomb all the time. Where we lived in Kent, we had an air raid shelter in our garden left over from the Second World War that my grandparents had dug and, while my little brother and I used it as a playroom, there was a sense we could go there to hide if we really needed to.”

The Cuban missile crisis would provide John F Kennedy with the chance to distinguish himself on the international scene, helping to usher in the Limited Nuclear Test Ban Treaty the following year.

If JFK was, for some at least, the technicolour future, in the UK the leadership of Harold Macmillan could be deemed as representative of the black-and-white past.

“Everything seemed brighter and bigger, more advanced and fun, in America,” said Nicolson.

“The glamour of President Kennedy was such an alternative to the old fusty Etonian, Harold Macmillan, with his walrus moustache. This was a time when there was a new generation – the teens of 1962 had no first-hand memory of either of the wars, unlike their parents and grandparents – so there was a sense of wanting to do things differently, to move on and move forward, and no longer accept the restrictions of the old ways of doing things.

“Specifically, the prejudices – against women, against people of colour, against people of other sexual choices.”

Peacock added: “When you think about it, the Macmillan government, and other governments around the world, had a not-insignificant number of people serving who took part in the Second World War or were significantly impacted by it.

“Macmillan is caught between two worlds of appearing very austere and of the old order, but at the same time looking forward – for example, he was the first prime minister to do prime minister’s questions and he was very media-savvy.”

Looking back, the frequency and volume of significant events in 1962 fairly takes the breath away.

“It was the year in which the first African-American student who went to the University Of Mississippi required an escort to campus by federal marshals amid riots as soldiers were deployed to ensure integration,” said Peacock.

“You can see the resonance with Black Lives Matter and civil rights today. Nelson Mandela was given a life sentence, eventually serving 27 years. Uganda and Jamaica gained their independence from Britain in 1962, as did Algeria from France. It was a time when Britain was trying to figure out its future in the world.

“The first telecommunications satellite, Telstar, was launched and relayed TV signals across the Atlantic, marking the beginning of the modern age of international TV and global transmission.”

The Profumo scandal, following the revelations of Secretary of State for War John Profumo’s affair with model Christine Keeler, also loomed large.

Nicolson said: “Britain’s minister of war was alleged to have slept with a woman who was also sleeping with a government spy. It was the conversation all through that winter, wondering if we could trust our own government.”

There can be many parallels drawn between the events causing concern in 1962 and in today’s society, not least environmental issues.

“Pollution was an issue,” explained Nicolson. “In Glasgow, the levels of pneumonia were higher than they had been in living memory. There was so little control over coal fires. The clean air act had come in but hadn’t really been implemented.”

In London, meanwhile, there were still people dying due to the smog. Pop culture was at the heart of change, too.

The Beatles released their first single, The Rolling Stones formed, and Marilyn Monroe passed away. And, while movies were increasingly reflecting what was happening in the world, television was having its own growing impact on people’s lives.

“In the US in 1950, one in 10 households had a television. In 1960, nine in 10 households had one,” said Peacock.

“It wouldn’t be dissimilar in the UK. 1962 is the beginning of the police procedural in Z-Cars, which faced some criticism at the time for its portrayal of police but went on to be very popular, as did University Challenge, also first broadcast this year.”

“Similar to lockdown, television was great comfort during the winter when everyone was kept inside and away from friends and family,” explained Nicolson.

“Not everyone had a set, but they got one during this time if they could afford it. That Was The Week That Was had 12 million viewers every Saturday and had people gripped. It attacked every part of the establishment and it’s hard to estimate how powerful the programme was.

“There was also Thank Your Lucky Stars, a music programme that featured this new, irreverent, wonderful-sounding band called The Beatles. By the time the frost began to thaw in March 1963, they would be No 1. There was an excitement to feel we had something better even than Elvis.”

Peacock added: “This was a Britain caught between different points on the winds of change. Events from 1962 still have resonance with us today, and we continue to feel that change.”

The Movies

Allan Hunter, co-director of Glasgow Film Festival, says its retrospective this year, Winds Of Change: Cinema In ’62, reveals how movies reflected the change gusting through a transformative year.

Ten retro classics will be shown as part of the festival, starting next month. Here, Hunter reviews some highlights.

The Manchurian Candidate

If any film speaks for the Cold War heating up and the paranoia of the times, it’s this one. It’s a tale of brainwashing, conspiracy, political monsters taking control of the world, prescient in terms of what would happen to Kennedy, and a once-in-a-lifetime cast including Frank Sinatra, Janet Leigh and Angela Lansbury. It’s a political thriller that still has resonance today.

To Kill a Mockingbird

This is a film that fits in with what was beginning to happen with the civil rights movement and the US addressing injustices of the past.

It’s about a white lawyer in Alabama defending a black man accused of raping a white woman and the prejudices it opens in the community, with the wider resonance of what America was trying to confront at the time. Such was its success, it was a way into the conversations for people.

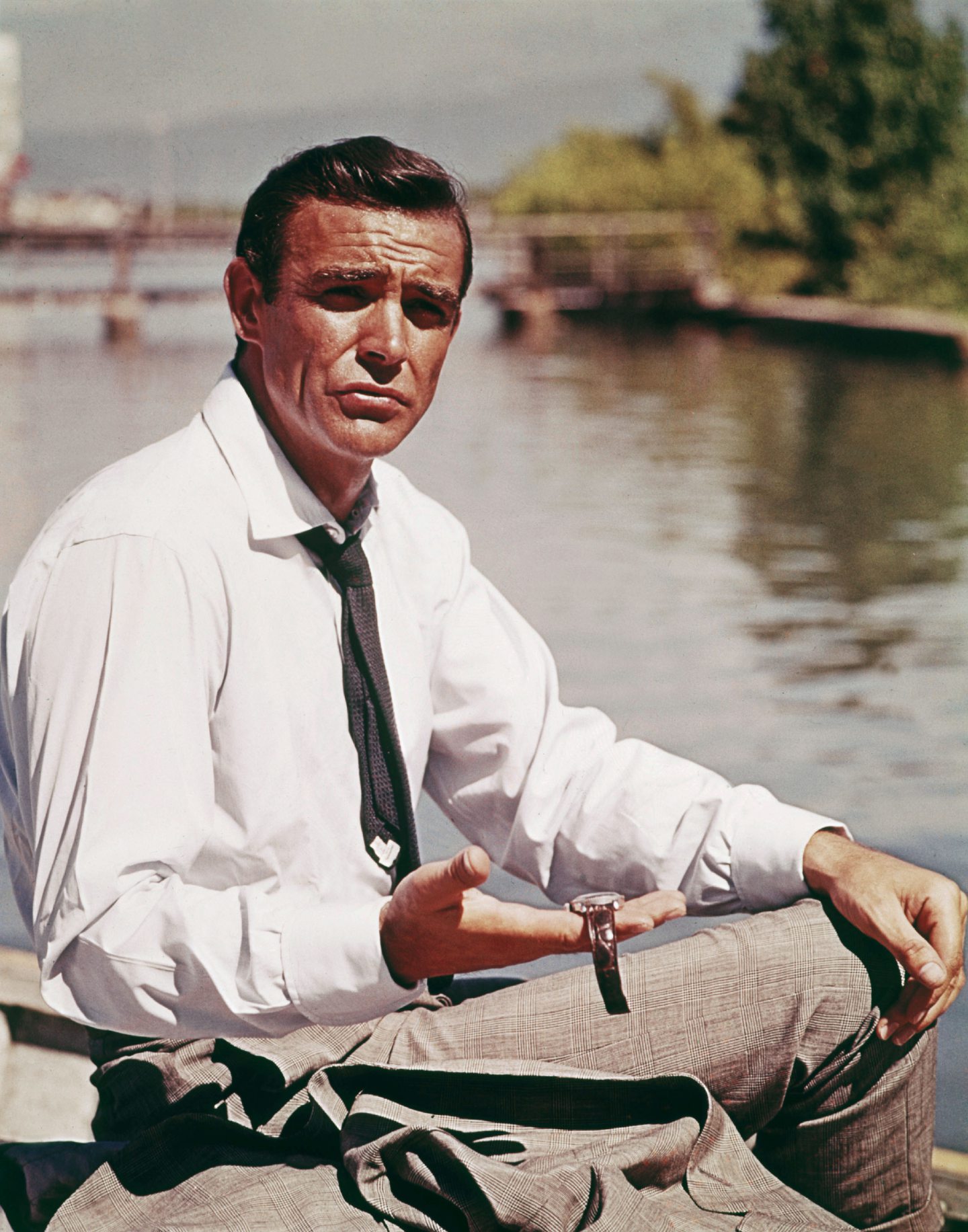

Dr No

As well as being the first Bond and catapulting Sean Connery to stardom, Dr No was also one of the films, as the ’60s were beginning to swing, that gave that swing a nudge.

Suddenly espionage wasn’t all shadows and darkness and people deciphering codes; it was now gaudy colours, gadgets and guns. Bond was a bit more fun and sexy, and injected some glamour for the time.

Lonely are the Brave

If 1962 was a moment of change and something was in the air in terms of moving on, then this reflects the end of an era.

Kirk Douglas is the modern-day cowboy trying to sustain the way he wants to live, as an independent maverick, but society is changing. This was an example of America’s open frontiers and sense of conquering and limitless opportunities maybe not being the case any more.

Lawrence of Arabia

This feels like the last hurrah for that big, sweeping epic, one man’s vision to go off into the desert and spend the best part of a year making it.

It’s also a bit more intelligent than your average epic in the way it tries to dissect this charismatic figure, with his flaws and virtues, suggesting the blockbuster was moving on – not just a celebration of heroes but the chance to see what makes them tick.

Frostquake by Juliet Nicolson is out now from Chatto & Windus; Glasgow Film Festival runs from March 2-13.

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe

© Danjaq/Eon/Ua/Kobal/Shutterstock

© Danjaq/Eon/Ua/Kobal/Shutterstock © Moviestore/Shutterstock

© Moviestore/Shutterstock