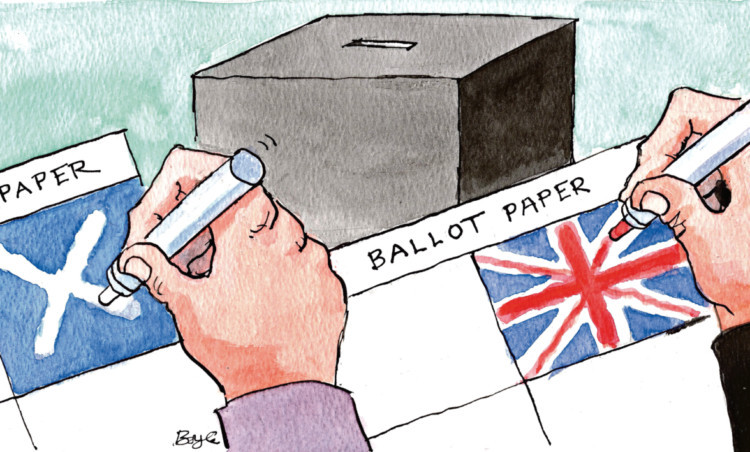

An end to governments for which Scots did not vote. It is one of the Yes camp’s most persuasive and beguiling arguments for independence.

It has also offered up one of the best lines of the independence debate that there are more pandas in Scotland than there are Tory MPs, yet a Conservative-led government runs the UK.

One of the drivers for devolution and still a sore point among many in Scottish politics of all stripes was the succession of Tory governments in the 1980s that simply didn’t command the support of Scotland.

It’s why Donald Dewar used to jokingly refuse to be referred to as the father of devolution, but quip that there was a mother of the Scottish Parliament and it was Margaret Thatcher.

A sovereign Scottish parliament elected only in Scotland would close what’s become known as the democratic deficit.

Westminster governments would not be able to inflict unpopular policies like the bedroom tax on a nation that did not vote for them. And, even though it happened a generation ago, the feeling, justified or not, that Scotland was used as a test lab for the poll tax still lingers.

There are two ways of looking at the democratic deficit.

First, does Scotland get the government it voted for? Since 1959, Scotland has returned a majority of Labour MPs and clearly Labour has not been in power in Westminster continuously since then.

It’s worth noting that before that, Scotland voted in mainly Conservatives and in 1951 it was Scottish Tory votes that saw Britain’s best peacetime PM, Labour’s Clement Attlee, evicted from Number 10 in favour of old warhorse Winston Churchill.

And that’s the other way of looking at it how often has the outcome hinged on Scottish results?

The answer is rarely. Apart from 1951, Scotland has affected only a couple of elections and predictably it’s been the tightest ones.

In 1974, Scotland put Harold Wilson back in power. In 2010, there would have been a Tory majority were it not for the 41 Labour MPs elected. So while Scotland didn’t get the Labour government it may have wanted, it prevented a Tory administration taking power.

The trouble is that if the SNP seek to demonstrate the democratic deficit by a number of MPs, they come up against a constitutional conundrum.

For, if General Election results show Scotland consistently backs Labour, how come it’s the SNP in power in Holyrood and driving the referendum agenda? If having just a solitary MP undermines the Conservatives’ legitimacy in Scotland, what of the SNP’s six Westminster members?

Their answer is that of course the SNP have the majority of MSPs. That majority in 2011 was unprecedented and unexpected and it has raised questions about the current parliamentary set-up in Scotland. The widely lauded committee system was meant to check and balance the Scottish Government’s power. But, with a parliamentary majority, the SNP have dominated the committees and it’s widely agreed those committees have largely proved ineffective in holding the government to account. It’s hoped that is just a temporary phenomenon while the dream of independence is pursued.

But it begs the question whether an independent Scotland would be better with a second chamber, like the House of Lords, to scrutinise and amend legislation. There’s an argument the work of the House of Lords is useful and maybe even essential.

However, the House of Lords itself isn’t a great advert for that argument since it costs in the region of £150 million a year to run and is stuffed with unelected members there on the basis of parentage or patronage. Accusations have resurfaced that some have in effect bought their way in via cash-for-honours. The SNP do not have any members in the Lords and won’t nominate any.

Gaining a written constitution would be the biggest symbolic step along the path to independence should Scotland vote Yes in September. A constitution setting out the rights of every Scottish citizen to education, to a clean environment and to live in a country without nuclear weapons for a start is probably the biggest change to Scotland’s democratic set-up planned by the SNP.

If Scotland votes Yes it would be odd if the new state did not have a written constitution. After all, only three countries in the world don’t have one and they make up a fairly random bunch New Zealand, Israel and the UK.

The most famous example is the US Constitution, signed by several Scots in 1787 and now a blueprint for a model democracy. Some historians claim it was influenced by the 1320 Declaration of Arbroath that saw Scotland assert its sovereignty.

The SNP recently unveiled plans for how that constitution would be drawn up with input from all sectors and citizens via a constitution commission. The Scottish Government has compiled a draft constitution to come into effect upon independence until a new one is agreed. That would give the SNP a head-start in deciding what goes into the final document.

But what does it mean to have something enshrined in a constitution?

The No camp claim that just because the right to education would be written down doesn’t mean the education system would be wonderful. It’s hard to imagine any government in Edinburgh, London or anywhere in the world acting to close down the nation’s schools, begging the question why it matters more if it’s written in a constitution.

Of course, a constitution can be altered. And it can contain clauses that look less clever with hindsight. Remember the Americans banned booze in their constitution, but only for a while.

The SNP constitution would enshrine the European Convention on Human Rights. But that’s already the case after Tony Blair’s first Labour government passed the Human Rights Act back in 1998. And ever since then there’s been controversy over it.

The Afghans who hijacked a plane and flew to Stansted used it to stop the Government throwing them out of the country and Home Secretary Theresa May famously told the Conservative party conference of an “illegal immigrant who cannot be deported because and I am not making this up he had a pet cat”. Unfortunately, she was making it up, but the judge that let that immigrant stay in the UK did reference his cat, but more importantly his partner, in the decision.

A constitution, then, is unlikely to make much difference to everyday life but it would immediately lend a new legitimacy to the new Scottish state. But there’s no guarantee having a shiny new constitution would improve the standard of politics.

The SNP want to keep Holyrood in its current form that means there would be many fewer politicians in Scottish life. That’s got to be tempting. There are undoubtedly too many in Westminster, with around 1,500 Lords and MPs altogether.

There are just 129 MSPs. But fewer members can mean more influence for those who are there.

The unwritten rules of how Britain works have evolved over time. A vote for independence will be a vote to put much more trust in MSPs.

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe