Will we still be best of pals in an independent Scotland?

Scotland being downtrodden by England is a story which has played out for centuries to varying degrees of accuracy along the way.

Today, a keen rivalry still exists between the two nations not least on the football and rugby fields but any notion of oppression is at the margins of the independence debate.

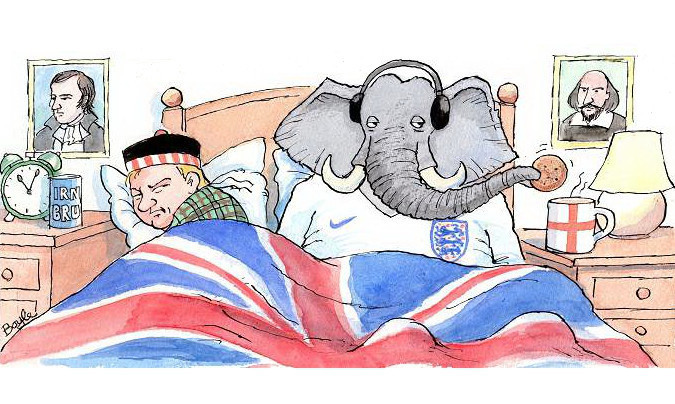

Or as the Scots historian and author Professor Christopher Whatley last week put it, “We haven’t been in bed with an elephant, or if we have it’s been a very benign elephant, a teddy bear.”

But could a Yes vote in September’s referendum stir up centuries-old bad blood with the Auld Enemy?

Or would it clear the air for a new chapter in an old friendship? The facts show we have come a long way from the Scots and English only ever meeting on the battlefield, with the two countries more than comfortable in each other’s company.

England is a far from an unwelcome place for Scots, otherwise more than 750,000 of them would not have made the country home.

Likewise, it is safe to assume the 366,000 English living north of the Border do not do so under duress.

In terms of trade, billions of pounds worth of goods flow between the two countries, with Scotland exporting twice as much to the rest of the UK as it does to the rest of the world.

And every year there are more than six million trips north of the border by English tourists.

Deep family and cultural ties cement the idea the two countries are inextricably linked but is any of this under threat if there was a Yes vote?

There will be English people who leave Scotland if there was a Yes vote, some out of economic necessity if threats about big employers moving out are actually carried through, but it is hard to see this happening in any great numbers.

Some argue that a common bond between friends and family who live either side of the border will be lost with the breakup of the UK but as the Yes camp point out, it is hard to envisage people ending personal relationships because they now no longer live in the same country as say their cousin or best friend.

However, the real test of the relationship between Scotland and England will depend on the deal struck at any post-Yes negotiations between Holyrood and Westminster.

Unlike when the Act of Union creating the UK was signed in 1707, where arrangements such as new customs and tax rates were

hammered out in advance, so much of what an independent Scotland would look like will be left up to negotiation.

Conducted in the right manner, these talks wouldn’t need to descend into a ‘Scotland versus England’ battle but there are a number of potential flashpoints.

The main one is the issue of border and passport controls, which will hinge on both UK and EU-level negotiations.

The Yes camp insist an independent Scotland will continue to enjoy the UK’s opt-out of the Schengen Agreement, meaning other EU citizens are still subject to passport checks on our borders because is outside the European free travel area.

But the UK Government claims this will not be possible and warns passport controls at the border would be needed because the Schengen bans free European travel between those who are part of the agreement, and those who are not.

Other potential flashpoints include what currency an independent Scotland would use and the consumer subsidies for renewable energy.

However, it is important to note all of these issues have implications for people living south of the Border as well, who could also face the hassle of passport checks or changing currency when coming to Scotland.

In the event of a Yes vote, the politicians running what remains of the UK will determine how much of an issue this is for their newly shrunk pool of voters before deciding on tough or consensual they will be in any negotiations. Where any post-independence carve-up will be most keenly observed will be in the North West and North East.

Politicians and business leaders in these areas are already wary and envious of what devolution has done for Scotland as its nearest competitor for investment.

If independence was to deliver cuts in corporation tax and air passenger duty, as is promised, then this could set Scotland on a collision course with the North of England.

For the North of England, being caught between tax-cutting Scotland and an all-powerful London is a difficult place to be. Alex Salmond has made a number of speeches south of the Border where he has insisted an independent Scotland and the rest of the UK would still be “closest friends”.

By contrast, in February David Cameron stood in the London Olympic Games site and issued a rallying cry to voters in England, Wales and Northern Ireland to tell Scots to reject independence, adding he could not bear to see the country “torn apart”.

The address was dismissed by the First Minister as the “sermon from Mount Olympus” but was also largely ignored by its target audience, many of whom feel they don’t really have a horse in this race.

The UK Government has to date focused its rallying call to the rest of the UK on the Union’s past triumphs rather than talking about what is at stake now.

The issues of what credit rating the rest of the UK would have, how its membership of bodies such as the UN or the G8 would be affected and what impact a cut in oil revenues would have are not on the table right now. It is for this reason that many in England are not fully engaged in the debate, many don’t see it as affecting them.

The referendum is an issue that affects the whole of the UK yet in the weeks following the launch of the Scottish Government’s white paper last year there was no debate in Westminster, the nation’s parliament.

Contrast this with the 1995 Quebec referendum where a “unity rally” held three days before the vote saw an estimated 100,000 people from the rest of Canada pour into the province to support a No vote.

Relations between Scotland and England have been civil for centuries now and this should prove to be a difficult habit to break, whatever the outcome of the referendum.

However, those with the biggest potential to damage this status by stoking up resentment are the politicians on either side leaving them with a big responsibility come September 19.

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe