Chemical attack suspect Abdul Ezedi was described as a “pleasant, friendly and cooperative man” and someone who was “always willing to help” in supportive letters from church workers as he applied to stay in the UK.

But a series of court documents which have been published also show how he had made an agreement to be effectively escorted at church services due to his convictions for sexual assault and exposure.

Details of the Afghan national’s conversion to Christianity while living in Newcastle were disclosed on Tuesday, almost two months after the Clapham attack.

His body was recovered from the River Thames in February, weeks after the incident in which police believe he threw a burning chemical over his former girlfriend, some of which also injured one of two children, and slammed a three-year-old’s head on the ground.

Ezedi’s conversion to Christianity and the role that played in his asylum claim sparked debate on the overall issue of the involvement of faith leaders in conversions and asylum applications.

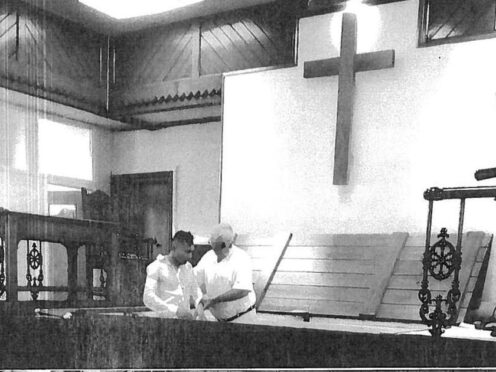

Documents from his lawyer in support of his asylum claim state that Ezedi began attending Grange Road Baptist church in Jarrow in February 2016, did an Alpha course and was “baptised by total immersion” on June 24 2018.

Grainy, black and white images of both his baptism and his so-called street ministry, whereby he handed out church leaflets to passers-by, are included in the documents bundle.

A letter from Reverend Roy Merrin, former ministry team leader at Grange Road Baptist Church, described Ezedi as having “established a good relationship with the other church members and is always willing to help as required”.

The letter, dated August 28 2018, confirmed Ezedi’s baptism and stated: “Abdul has been ready to share his faith in Christ with non-Christians.

“I hope that this information will be of assistance, and I would support his application to remain in this country.”

The letter came eight months after Ezedi’s sex offences conviction.

He avoided jail after pleading guilty to charges of sexual assault and exposure, instead being placed on the sex offender register for 10 years and ordered to carry out 200 hours of unpaid work when he was handed a suspended sentence at Newcastle Crown Court on January 9 2018.

Ezedi was accused of grabbing the bottom of a woman without her consent in 2017, as well as committing a sex act that same year, according to documents detailing the indictment which were disclosed by the court to the PA news agency in February.

An undated document entitled “safeguarding contract”, in Ezedi’s name, set out the conditions for his attendance at the Baptist church, in light of his convictions.

It included a requirement that he had to “stay in the vicinity” of an appointed male supporter during services and was not allowed to sit alone in church “at any time”.

Following publication of the documents, Baptists Together, a movement of more than 1,800 local churches of which Grange Road is one, said it “did not corporately support or sponsor” the asylum application, and that the personal letter of support “commenting solely on Abdul Ezedi’s observed faith journey was written by a retired Baptist Minister”.

The safeguarding contract was agreed between the church and Ezedi and was “to show the church had sufficiently risk assessed Abdul Ezedi’s attendance at church, ensuring the safety of the congregation and considering if it was appropriate for him to attend”.

Baptists Together said: “The Home Office make the final decision on asylum applications and have access to full criminal records data to enable them to do this.”

Also in the documents bundle was a separate letter in July 2017, pre-dating Ezedi’s convictions, which saw him described by a project worker at the Catholic Diocese of Hexham and Newcastle Justice and Peace Refugee Project as a “pleasant, friendly and cooperative man”.

It detailed how he attended the project each week and “signs for a bag of food” as well as being given £25 in cash each month.

In support of his asylum claim, Ezedi’s lawyers stated that his conversion from being a Shia Muslim to a Baptist Christian would be publishable in his native Afghanistan by execution.

Collingwood Immigration Services, a Newcastle solicitors’ firm, argued that the “evidence of his conversion is clear and cogent and has been over a considerable period of time, more than three years”.

The lawyers stated: “We submit that his conversion is one which should be accepted by the Home Office as being genuine.”

They added that Ezedi was “clearly someone who enjoys practising and sharing his Christian faith with others”, referring to the photographs of his street ministry.

The lawyers said he attended weekly services at the Baptist church which he “greatly enjoys” and would not be able to openly practise his new faith in Afghanistan “without considerable risk to himself”.

A spokesperson for the Diocese of Hexham and Newcastle said the letter from the project worker was “issued to assist with support from other agencies and not as part of an asylum claim”.

They added: “The Diocesan Justice and Peace Refugee Project is a charitable venture set up to serve people in severe need, providing, for instance, food parcels donated by individuals or parishes.

“Occasionally in cases of hardship it also gives a small donation in cash and supports people with second-hand clothing or shoes.

“It is not involved in asylum casework.”

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe