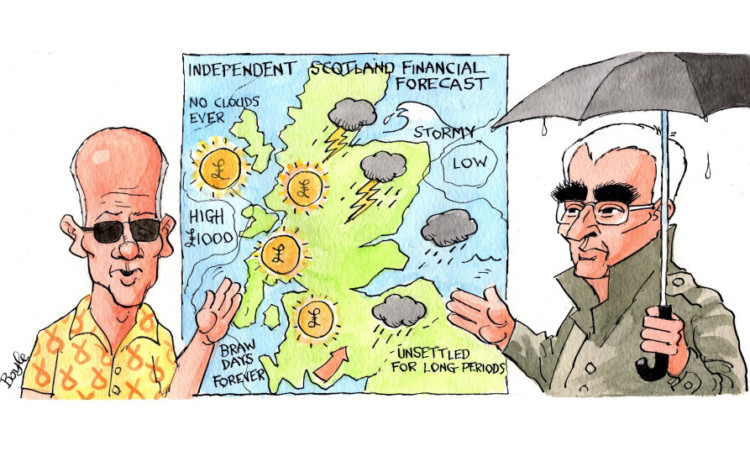

Both sides in the indy ref debate are able to produce plausible projections for the future of Scotland but does sunshine or storm clouds lie ahead?

Over the last few weeks the Yes and No campaigns have both been claiming people will be better off if they vote for or against independence.

The Treasury in Whitehall says everyone is £1,400 better off in the union. The Scottish Government says Scots will be £1,000 per head richer under independence. They can’t both be right, can they? Well, yes. Sort of.

For both are talking about the future, and you can’t be wrong about something that hasn’t happened yet. Also, unfortunately, neither is talking about cash in hand.

Vote Yes in September and a cheque for £1000 won’t drop through your letterbox, vote No and The Chancellor won’t be round to press £1,400 into your palm.

The dividend, if there is one, will come in the form of lower taxes and better public services. Or rather less worse public services given the austerity agenda currently deemed necessary.

Indeed, given the economic outlook the argument over whether Scotland can pay its way looks less like two bald men fighting over a comb and more like two combs fighting over a bald man.

Both sides’ projections for the future look to the past in the first instance.

For decades the Treasury has produced the Government Expenditure and Revenue Scotland (GERS) figures providing a picture of Scotland’s economic health.

The idea originally was that the data would show how well Scotland did within the union. But the SNP use it to support their claim that Scotland would thrive on its own.

The GERS figures for 2011-12 showed Scotland, with just over 8% of the UK’s population, accounted for more than 9% of public spending and paid in nearly 10% of the taxes.

A lot of that tax take came courtesy of oil and gas, of course. We’ll look in more detail in future weeks at the arguments over who gets how much of the North Sea’s bounty in the event of independence.

However, the latest GERS figures, for 2012-13 show more Government money is spent in Scotland per head of population than it is across the UK around £1,300 extra, though it’s worth pointing out the UK Government borrows to make up that money.

But Scots also contribute an additional £800 each in tax.

Those same figures released in March show that Scotland’s deficit the gap between how much money the Government brings in and how much it pays out on services including hospitals, schools and roads had increased.

That change was largely due to a drop in how much the oil sector contributed. Oil prices and volumes and therefore the amount of tax it generates can vary wildly.

Westminster says this is an example of the danger Scotland would face if it relied on oil to prop up its economy.

That’s a bit disingenuous. A large part of the reason oil revenues fell last year was that Westminster started offering tax breaks to encourage investment in the North Sea and cut the taxes that they hiked on taking power in 2010.

But there’s no doubt that in the long term returns from oil and gas will fall as stocks in the North Sea are used up.

So if both sides in the debate can argue over the figures already generated what chance any sort of agreement over the future which is notoriously tricky to predict?

The Coalition Government set up the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) after taking power in 2010 to provide accurate economic forecasts unaffected by political colouring. But the OBR has consistently called the economy wrong.

And the numbers produced by the Treasury to inform its economic analysis of independence rely fairly heavily on the OBR.

You can look at that two ways. One view is to say that if the OBR, with access to mountains of official data, can’t forecast the economy right then what hope have the SNP got working with much less information?

Another is to argue that if even the OBR are fallible then the SNP have as much chance of being right, or wrong.

However, the Government argument was bolstered last week by a bombshell report from the Institute for Fiscal Studies (IFS).

The independent IFS seems to take great pleasure in picking George Osborne’s Budgets apart every year so it’s no friend of the Treasury. But it has slammed the SNP figures.

The Institute says Scotland would face a relatively bigger deficit than the rest of the UK upon independence £8.6bn which it describes as “not sustainable for any prolonged period”.

The way to balance the books is either to bring in more money, and that means higher taxes (booting basic-rate income tax up to 28% would be one way to make a start), or make further cuts and spend less.

The trouble is that the SNP’s White Paper on independence contains a number of spending commitments.

It pledges to abolish the bedroom tax, cut corporation tax and airport passenger duty (APD), delay increasing the state pension age and, most eye-catching of all, provide free childcare for pre-school children.

The price tag for all that is estimated at around £1.2bn a year.

The IFS admits that some of the changes might also generate more income. For example, the Scottish Government claims the childcare pledge will encourage more women into work and clearly they’ll pay tax. But the IFS backs the Treasury in trashing the SNP projections.

It seems even if every stay-at-home mum went into paid employment, another 21,000 people would need to be found to generate the sort of revenues the SNP are banking on. And extra people means immigration.

The House of Commons library did research showing Scotland would need an extra 24,000 per year to defuse the demographic timebomb caused by having a population profile ageing more rapidly than the rest of the UK that means more people are needed in work to pay for the pensions and benefits of those retired.

The SNP have committed to a more lax immigration regime than that favoured by Westminster. If the Scottish economy were to motor as the SNP predict it would be in large part fuelled by immigration.

They are also pinning their hopes on increased productivity, which is something even their own experts point out is very hard to predict.

The nub of the issue is whether the Scottish economy would become a powerhouse once unshackled from an economic policy drawn up in London “shackles” that currently mean more is spent in Scotland than in any other part of the UK.

The Scottish Government say it would, with immigration and oil the driving force and productivity rising. They could be right.

However, most independent observers query the SNP’s oil forecasts and consequently the prospects for an independent Scottish economy. Scotland would not go bust should it embrace independence.

But it’s wrong to pretend that separation would mean an end to austerity and there are plenty of experts who say the economic choices to be made would actually be even harder.

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe