Sunday Post writer Chae Strathie reveals his experience of depression and the impact antidepressants had on his life.

Five weeks ago I wrote about my experience of depression. Little was I to know that just over a month later the subject would be filling newspaper columns and being discussed at length on TV and radio stations around the world.

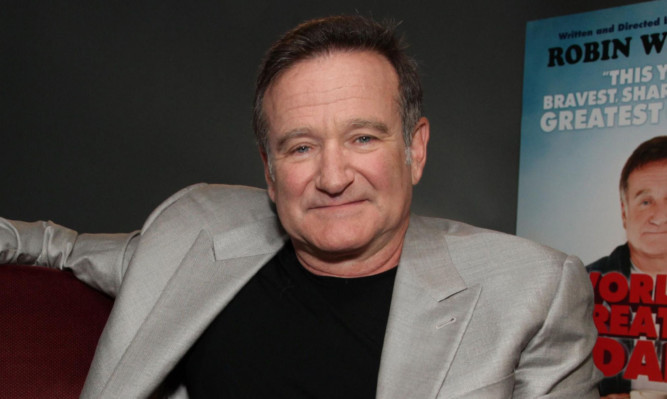

The sad reason for the spotlight to be shone so starkly on the issue was the tragic suicide of actor and comedian Robin Williams on Monday.

How could someone so popular, so well-loved, so successful come to take their own life, many people wondered.

The harsh truth is that depression is an illness that can affect anyone – the poor and the rich, the lonely and the loved, the struggling and the successful.

It is a hidden affliction, one that can be buried beneath a “brave face” and a “stiff upper lip”. And that’s what makes it so dangerous. As Robin Williams’ death showed, depression can be a fatal illness.

Perhaps one positive legacy of his passing will be that people will begin to talk about depression more. As I know myself it can be difficult to raise the subject.

You feel weak, embarrassed and self-conscious. You don’t want to bother people with your woes. Sometimes you simply want to hide in a dark room. Talking is the last thing you feel like doing.

But seeking help and being open about your illness is, in the end, the best perhaps only way forward.

If you are unlucky enough to be one of the many people who suffer from depression to any degree, you have to try to find the strength to trust others to help you even when you feel that there is nothing that could possibly pull you out of the dark place you are in. And as a society, as friends, as family we all have to be willing to listen to people without judging them or telling them to “pull themselves together”.

It is only through those on both sides of the equation the ill and the well accepting that depression is nothing to be ashamed of that we can truly begin to take on this secret scourge that cripples and kills so many people.

The piece below was first published in The Sunday Post on July 7 this year.

It was revealed last week that more than £40 million was spent prescribing antidepressants in Scotland last year up more than £10 million on the previous year.

Over the same period the number of antidepressants dispensed increased by more than 275,000 from 5.2 million to almost 5.5 million.

Mental illness will affect one in four people at some point in their lives and as a nation we seem to be ever more reliant on pills to deal with depression.

Sunday Post writer Chae Strathie was one of those who turned to antidepressants for help. Here he reveals why he needed them and what effect they had on his life.

“You’re pathetic, you stupid, boring, worthless idiot. Just look at you. You’ve nothing interesting to say to anyone. You’re dull, you’re fat, you’re useless, you’re a snivelling coward. What is the point in you? Why are you even here?”

The voice my voice kept on and on and on, flooding my head with so many crushing, negative thoughts it felt like it would burst.

It was as if someone had turned on a tap in my brain, releasing a gushing torrent of destructive words and images, and no matter how hard I tried I couldn’t turn it off. In fact, the more I focused on stemming the flow, the worse it got.

This wasn’t the usual self-critical, crisis-of-confidence, hectoring voice you, I and probably everyone else experiences from time to time. This was different. This was relentless. There was no escape from it. It was there when I went to sleep and it was waiting for me when I woke up in the small hours of the morning.

I remember clearly being in the car driving home from work one day, barely able to concentrate on the road for the roaring deluge battering my skull from the inside.

Just need to get home. Crawl into bed. Pull the covers over my head. Be still. Be dark. Be quiet. Try to sleep. Make the thoughts stop. Tears welled in my eyes and streamed down my cheeks. Why was this happening?

How could I make it stop? It would never stop, would it? There was no way it would ever end. No light at the end of the tunnel. No hope.

I’d been suffering this excruciating emotional onslaught for a couple of weeks by that point, and I had no idea what sparked it. It was summer, everything was fine at home and work, I had a nice house in a nice village by the sea.

I’d suffered no bereavements, no unusual pressures. Nothing. Then this.

My mood alternated wildly between the turmoil of chaotic pessimistic thought and a deep, dark, hollow emptiness.

Winston Churchill famously referred to his “black dog”, those times when he was consumed by melancholy. The dog analogy suggests there was something “there”, something dynamic and strong dragging him down, devouring him.

But for me and the key here is that everyone experiences depression differently it was the absence of anything at all that typified those periods.

It was more black hole than black dog. A vacuum of emotion. No joy, no anger, no sadness even. Just a bleak void.

It sounds melodramatic now, with the benefit of hindsight. But at the time it was all too real and impossible to see a way out.

Of course, being a Scottish male in public I put on a brave face and told no one about what I was going though. If bottling up emotions was an event in the Commonwealth Games, Scotland would sweep the field. When it comes to keeping schtum about feelings, we’re world-class.

My wife knew something was up. How could she not? Spending two hours in the bath (warm, quiet, comforting) and going to bed at 6pm every night tends to give the game away. But still I didn’t reveal the full extent of my fear, the bedlam of my thoughts, the depths to which my mood had sunk, the utter desolation.

It’s a guilt I still carry with me. The feeling that somehow I let her down by not opening up. That she felt I didn’t trust her. But that was never the case. It’s hard to put into words, but sometimes it can almost feel easier revealing emotional torment to a complete stranger than someone you love.

Finally, after several weeks of agony, I knew I had to seek help. I made an appointment at my local GP surgery and trudged along to the health centre on the allotted day.

The doc wasn’t one I’d seen before. He was young, seemed fairly new in the job, but had a pleasant manner. He asked what the problem was, and I began to explain. Before I could finish the first sentence I was sobbing uncontrollably.

I think I babbled something about a tap in my head, feeling scared then empty, not wanting to get out of bed. You know, the usual.

I remember he had a slightly wide-eyed expression on his face, like I was the first wailing, unshaven 35-year-old he’d encountered in his career up to that point. He reassured me it wasn’t uncommon to feel low sometimes and said he would prescribe me some antidepressants that would help.

And that was it. In and out in a jiffy. I left clutching my prescription, slightly dazed and not entirely sure if I was relieved not to have had a long conversation about my feelings or disappointed that there hadn’t been more emotional support.

I started on the antidepressants citalopram and after a while, almost without realising it, things started to get better. My mood stabilised, the bleakness eased and the gush of relentless negative thoughts slowed to trickle … then stopped. The tap had been turned off.

The pills had given me just enough of the lift I’d needed to get my head above water. For that I will be forever grateful.

The thing is, as the months went on and I kept popping my “little friends” I felt, well, nothing much. They had stopped the anguish, but now I seemed to be practically emotionless. Everything was flat.

Bad things happened and I was far less affected than I should have been. Great things happened and I felt little joy. I was pleased, but it was a muffled pleased. It was as if my emotional responses had been wrapped in cotton wool. They were safe, but also dulled and overprotected by the pills.

I wanted to feel again, so with the GP’s advice and not a little fear that the depression would return I eased off the citalopram. If you’re in a similar position this is incredibly important.

Stopping your medication suddenly and without advice can be problematic, with side effects ranging from anxiety and fatigue to dizziness and headaches. Always check with your doctor before coming off antidepressants.

Since then I’ve never had to go through anything like that experience. Yes, sometimes the voice in my head tells me I’m stupid or fat or boring and sometimes it’s right but show me a human who doesn’t hear the same kind of things from time to time (though hopefully not in my voice).

And sometimes that old black hole appears, sucking the light from the stars and the joy from life. But I’ve learned to understand that it will pass, as all things must.

Antidepressants aren’t the answer for everyone and there are certainly down-sides to taking them, from specific and sometimes severe side effects, to that “cotton wool” feeling I mentioned above. But they gave me the lifeline I needed.

You have to do what’s right for you. Talk to someone if you feel you can. Share your feelings with a partner, a friend or a perfect stranger on one of the many helplines that are available. See your GP.

Ask for help, whether it’s in pill form or through a talking therapy. But most of all cling on to the hope however tiny it seems, however fleeting that the darkness and despair will pass. Because even though it might not feel like it now, one day it will.

Help is out there

Tony McLaren, the national coordinator of mental health charity Breathing Space, works to combat the difficulty people have in speaking freely about depression to loved ones or their GP.

“It is easy to go to your doctor to have a sore foot treated but many feel mental health has a stigma,” he said. “They often feel they will stigmatised or seen as less able to cope.”

He also revealed that 800,000 Scots say they do not know where to turn for help with depression and other mental health issues. Family and friends can struggle to cope because they feel helpless, Tony suggests.

“They do not see physical injuries which immediately prompt support and sympathy. After two or three weeks family can be worn down and tell relatives to pull themselves together when in fact they need to see a doctor.”

He believes GPs are on the whole good at treating depression, through antidepressants, talking therapy or other treatments. But he warns patients on antidepressants not to abandon them because they feel better.

“They have improved because they are on the drugs, most likely,” Tony stressed. “To come off without their doctor’s approval may cause the depression to return.”

GP Dr Alan McDevitt sees three patients suffering from depression at every surgery session, with 150 patients being treated in his 9000-patient practice. But the Clydebank doctor says he would hate to see a ban on the antidepressants.

“Try telling that to families who have struggled and suffered with mums, dads and other loved ones who have been blighted with serious depression,” he argues.

Dr McDevitt, chairman of the BMA’s Scottish General Practitioners Committee, says drugs used with talking therapies are effective. “It helps patients identify why they are depressed and how they can use strategies to cope.”

But the waiting list for talking therapy is three months, Dr McDevitt adds.

Britain consumes more anti-depressants than almost all our neighbours in Europe, an international study has revealed. Experts fear the drugs are overused to treat unhappiness, rather than depression.

One NHS worker told us getting help as soon as possible is vital. “There’s still a very British, stiff-upper-lip attitude about this subject,” she said. “People just need to realise they don’t have to be like that. The help is there for them.”

Mental health charity Breathing Space can be contacted on 0800 838587. Mind which provides information on where to get help can be contacted on 0300 123 3393 or via text on 86463.

Their website www.mind.org.uk has useful tips on medication, debt and symptoms.

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe