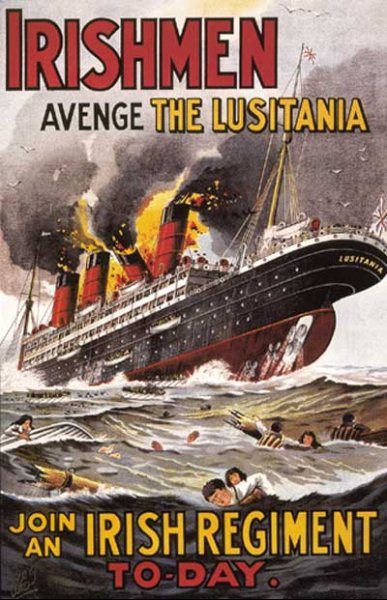

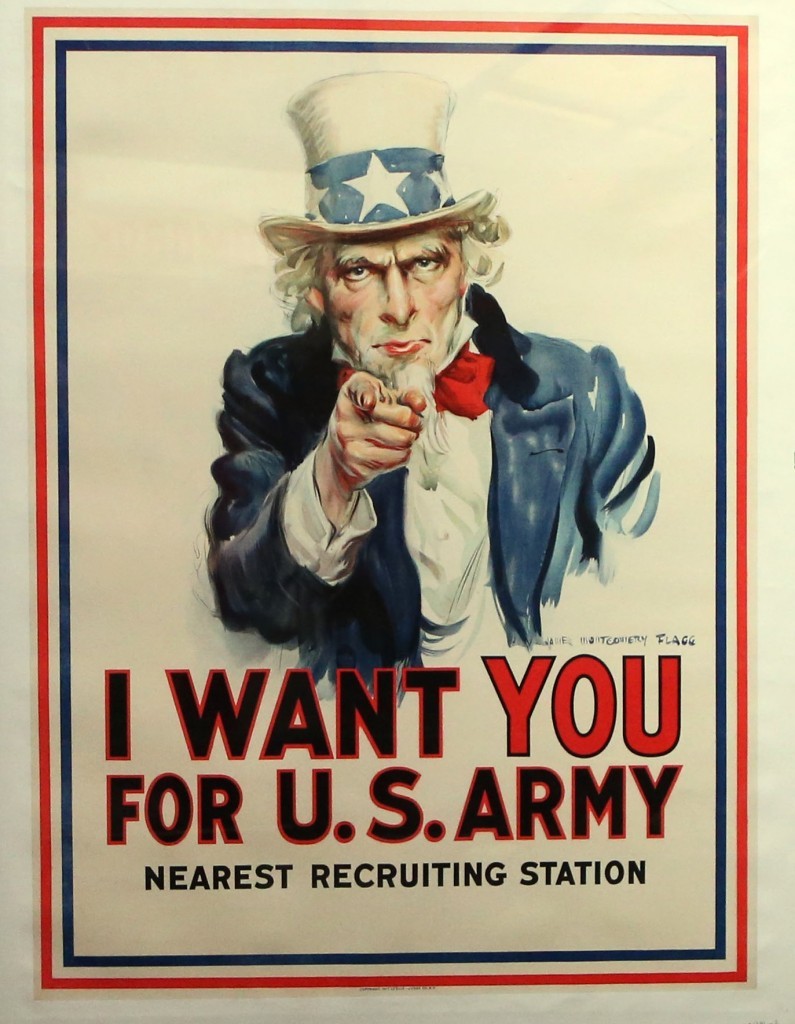

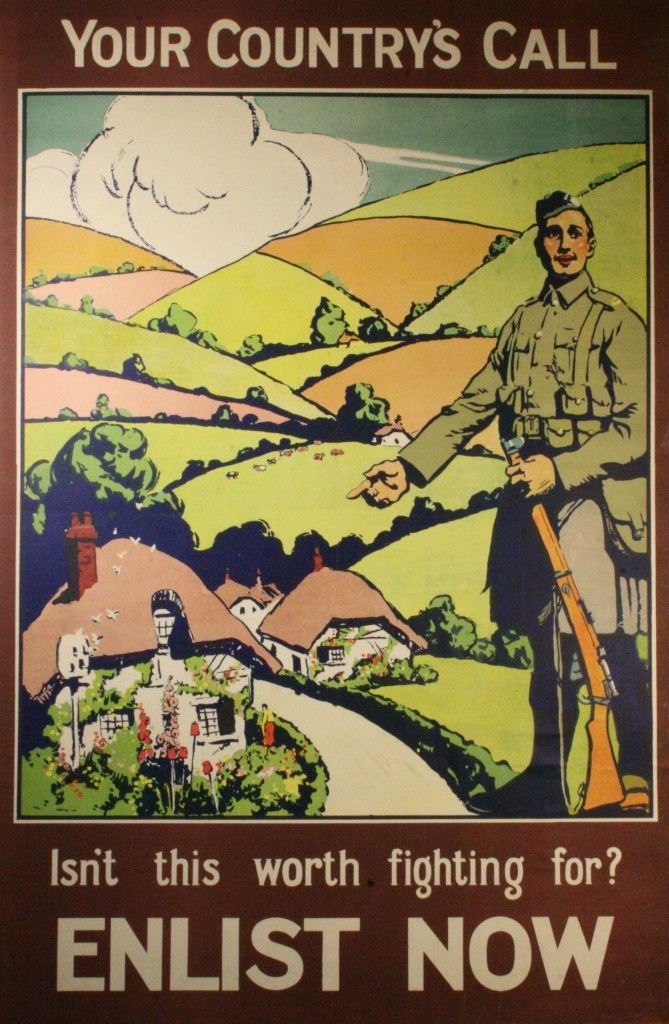

However, while today’s billboards are all about selling cars, clothes and everything else, in 1914, it was a matter of life and death.

Persuading lads to join the Army, and making sure the population remembered to watch who was around when they spoke, were the main ideas.

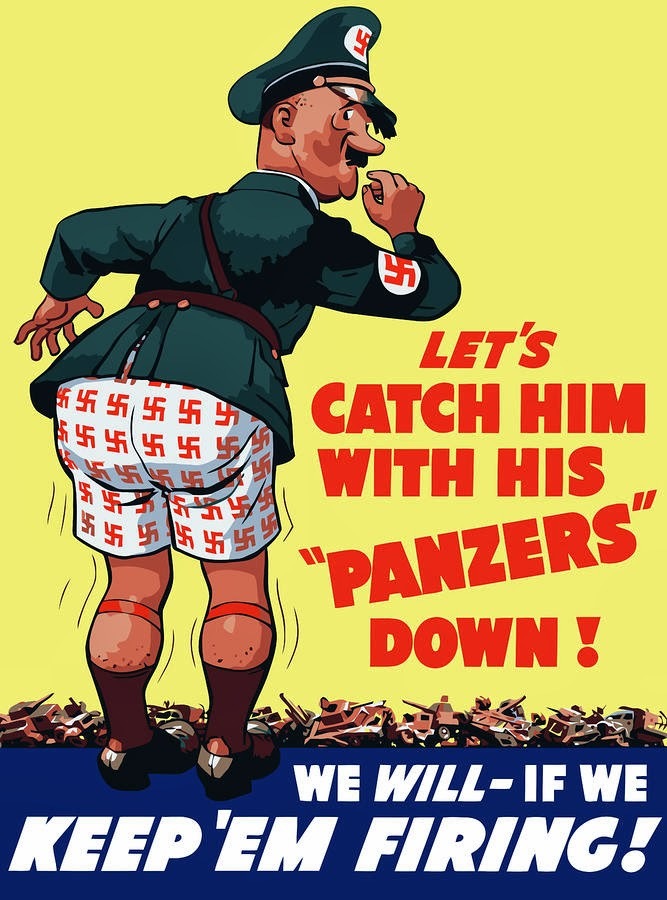

Also, of course, we were urged to think about what was at stake, and many a poster showed Germany as an evil nation who would be capable of anything if we didn’t stand up to them.

Britain, in fact, was forced to use propaganda posters during the First World War — while countries like France and Germany already had National Service policies, we didn’t, and they were the best way to attract thousands of men quickly.

Even the posters weren’t enough, though, and conscription was brought in to boost the numbers.

While recruitment posters would be used throughout the war, they would take on a new look as the conflict dragged on — and anything that stressed the importance of winning, and the evil of our foes, was fair game.

Buying special bonds to help the war effort, and being thrifty at home, were other popular subjects.

Propaganda posters in wartime have been used ever since.

One of the best-known was the Second World War’s Dig For Victory poster, urging us all to grow our own food.

Having seen the information on walls, shop windows and leaflets, or heard about it on radio, you could see it in more detail between films at the local cinema.

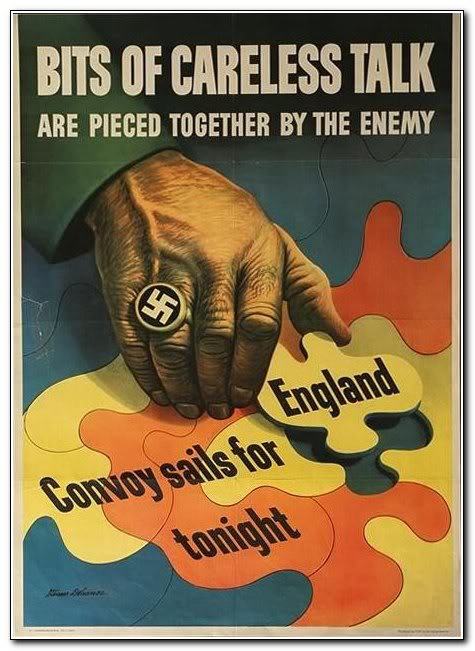

The Government’s Ministry of Information, formed in 1939, became expert at reminding us how serious things were, how loose tongues could lead to trouble, and all the little things those left at home could do to play their part.

Ironically, propaganda had played a darker part in Germany, where posters tried to portray the Jewish people as sub-humans who had to be got rid of.

Others would show Russia’s Red Army as a horde of savages, and before 1939, they’d shown Hitler as a peace-loving chap who merely wanted to give Germany’s lost territories back to them.

Paintings and posters would make him look like a real leader, something that meant a lot in German tradition — the idea of one man who is so sure and reliable appealed to them.

So Hitler would always look noble and serious, like a man who knew the answer to all their problems, and could be trusted totally.

Other posters encouraged the German population to Save For Your Own Car, so both sides were being asked to count their pennies and be money-conscious.

As the war went on, Britain saw the first posters asking us to increase arms production, to help countries far from the UK.

Rush British Arms To Russian Hands was a reminder that our allies in the East could only play a big part in eventual victory if they had guns in their hands and bullets to fire.

It would seem a bit ironic, not many years later, as the Soviet Union became one of the real masters of propaganda, in posters, films, books and everything else!

Posters of young Russian boys, playing with their toy planes while real ones fly overhead, appealed to family-conscious Russia.

And ones of Stalin holding Russian babies in his arms, while they proudly flew the Soviet flag, had the same effect — before long, boys and girls of every age were queueing up, begging to enlist.

Then, as now, though, the Russians had problems getting along with their Ukraine neighbours — one poster, Two Boots Make A Pair, suggested that some in Ukraine were collaborating with the Nazis.

After D-Day, the posters became more vivid, as the Germans grew desperate — they would drop leaflets from planes for British and American troops to read, suggesting the Soviets were like wolves who would turn on them next.

If it was meant to spread panic among the Allies, it failed — they also dropped similar leaflets on Holland, hoping Dutchmen would join them in the fight against Russia.

In America, posters of a gigantic soldier, with one German head and one Japanese, showed the creature smashing the USA and crushing the Statue of Liberty.

It got the intended result, as US workers increased their production of arms and essentials.

And even in the 1980s, the Soviets were still relying on powerful posters to portray America as their most-bitter enemy.

A huge monster, part Ku Klux Klansman, part Miss America winner, part Jitterbug dancer, was shown gobbling up the world on its “imperialist mission”.

It was posters like this that had kept millions of Russians from questioning why life outside the Soviet Union was supposedly so much better.

Even Pablo Picasso got in on the act, and his painting of Guernica was done to show all the horrors of the Spanish Civil War — around the world, foreigners who had known nothing about it were suddenly looking at Spain, and asking questions.

Guernica had been horrifically bombed by German and Italian air forces.

Jim Fitzpatrick had been an Irish student when he met Che Guevara in Ireland in 1963.

Shocked by the revolutionary’s death, his famous poster of Guevara would be seen on walls across the world, and became the inspiration for many riots and battles.

Even today, propaganda posters are used whenever someone wants somebody else to react a certain way, to believe something that might not be quite right.

And we don’t just mean when our political parties want our votes!

One thing’s for sure — as long as people start wars with one another, there will always be people in the background, dreaming up the latest propaganda poster.

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe