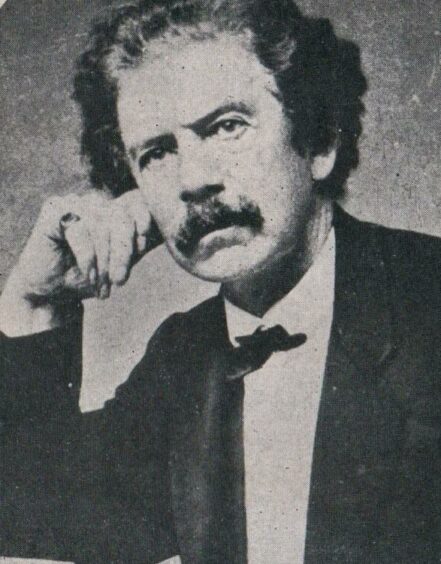

Today his name is forgotten, his music unplayed but Reginald Foresythe is, at last, being placed where he belongs in the pantheon of pop pioneers.

Gay and black, half-Scottish and alcoholic, the pianist is an unlikely legend but author Bob Stanley is certain of his enduring influence on our culture.

“His story is incredible yet it’s not widely known,” said Stanley. “He grew up in a wealthy family in Mayfair. His Nigerian father died when he was young and he was brought up by his Scottish mum. He was gay and he was black. His story almost sounds fictional it’s so incredible, but the music is the most important thing. If that wasn’t good, none of it would matter.

“He travelled the world and became obsessed with jazz, going to America to meet the musicians. He was really interested in channelling jazz and classical music in a commercial way. Musically, he was around 20 years ahead of his time. When you hear some of his music, you imagine it must have been influenced by the likes of Duke Ellington from the 1940s and ’50s, but then you realise it can’t be because he wrote it in the mid-’30s. He was genuinely ahead of his time.”

Foresythe is, according to the respected music historian’s new book Let’s Do It: The Birth Of Pop, one of the musicians “whose work hovers on the edge of extinction”, like film composer Harry Warren and jazz singer Annette Hanshaw whose work is as influential as the all-time greats, the Presleys and Sinatras, but only known by a dwindling band of fans.

The book, a follow-up to Yeah Yeah Yeah: The Story Of Modern Pop, traces popular music’s origins back to the late 19th Century and, gripped by Foresythe’s incredible riches to rags tale, Stanley describes the pianist as one of the “secret heroes of this story”.

Born in 1907, Foresythe’s travels in the late 1920s saw him settle in the US, where he quickly gained a favourable reputation in the jazz fraternity. He wrote for famous Chicago band leader and pianist Earl Hines, even composing Hines’ signature tune, Deep Forest.

Duke Ellington, a pivotal figure in the history of jazz, was so impressed by his playing that he let Foresythe stay in his apartment on a semi-permanent basis. However, this show of hospitality, Ellington soon learned to his cost, was a mistake.

“Foresythe was a terrible alcoholic and he trashed it. He also regularly got into fights in gay clubs and bars,” said Stanley. In what he describes as “the most forward-looking British sound of the decade”, The New Music Of Reginald Forsythe was unveiled on October 17, 1933, described by the press as distinctive but difficult to dance to but the innovative instrumentation consisting of just reeds and a wind section ensured his star was on the rise and the likes of Louis Armstrong recorded his music.

Stanley, who is also a founding member of enduring indie favourites Saint Etienne, says that being black, gay and British, Foresythe must have seemed like he was beamed down from Mars, but he was awash with confidence.

“He was very intelligent. There are quotes from him in an Australian newspaper article where he argues the case very well about racism and talking about musical progression,” he said. “People felt he knew what he was talking about, and he also had the money to back himself up, which must have helped. He must have been very confident to get as far as he did.”

His fame and acclaim began to dim when the simplified sounds of swing grew increasingly popular.

“He was on the verge of becoming really famous when swing, which was much more basic, something he didn’t like, came through. He wanted it to be much more complicated and his sound became unfashionable overnight.

“Then the war broke out, he got PTSD and that was sort of the end of his career.”

Foresythe’s drinking grew worse after his time in the RAF and he ended up playing clubs in Britain in the late ’40s and ’50s, his name forgotten, and he died in 1958, just as the music he pioneered was achieving a commercial breakthrough.

The tragic story is just one of the many tales Stanley uncovered in the nine years it took him to complete the mammoth tome on pop music’s genesis. “I set parameters otherwise I could have gone on forever,” he admitted. “Everything fell into place around 1900, so that’s where the book starts.

“The beginning of the 20th Century is when sheet music became mass manufactured and records started being pressed for people to play on record players at home. It also coincided with ragtime, the first real form of American popular music.”

Ragtime, blues, country, jazz, Tin Pan Alley – fitting all the pieces together and into a discernible timeline was a giant puzzle Stanley had to solve before the story would make any sense to him.

Also, writing about the early to mid-20th Century, Stanley had to look at the prejudices prevalent at the time.

“I constantly had to remind myself to look at whether someone becoming successful was to the cost of someone else.

“Not just R’n’B and black songs, but country music, which in America was seen as an underclass and those sorts were there to be pilfered by New York to make money from. I’d be setting myself up to look like a fool if I ignored the real roots of a lot of this music, and I also wanted to give these musicians a space they hadn’t had before, because so many histories written in the ’50s, ’60s and ’70s ignored it.

“It’s the same with female musicians – the swing bands of the Second World War were largely made up of women. I’d heard of the likes of Ivy Benson but I hadn’t realised how prevalent it was.

“They were seen as eye candy at the time, but they are clearly very good players. Yet as soon as the war was over, that was it. It’s really shocking. Someone like Ina Ray Hutton was an amazing performer and bandleader, so I wanted to put the stories of people like her down on paper.”

With the war resulting in fewer bands, solo performers came to the fore. Names such as Frank Sinatra, who transcended styles and generations, became stars.

“He and Ella Fitzgerald were recording albums that would become known as the Great American Songbook but back then it was just considered popular music,” said Stanley. “Those Sinatra albums of the ’50s on Capitol Records, almost all of the songs were at least 15 to 20 years old, because songwriting in the early ’50s had gone down this odd child-like rabbit hole – songs like (How Much Is) That Doggie In The Window, which was written by Bob Merrill, then the biggest songwriter in America.

“Clearly Sinatra didn’t have the time of day for things like that.This is before rock ‘n’ roll, but already there is a real divide. People had become aware a golden era had come to an end in American songwriting.”

Stanley, who is now working on a book about The Bee Gees, discovered the term “pop music” was first used in trade newspaper The Stage in 1901, where an advert mentioned “All the latest pop. music”, the full stop there to make it snappier and cheaper to print.

He was willing to read entire books if it led to one interesting anecdote or quote he could use, such as Fats Waller being kidnapped by Chicago gangsters because Al Capone wanted him to play at his birthday party, or J Edgar Hoover asking Sophie Tucker if he could borrow one of her dresses.

He will launch Let’s Do It at Glasgow’s famous record shop Monorail on Tuesday, adding: “Because the book is covering a lot of ground people aren’t familiar with, and rather than just talk up on stage, I’ll have a couple of musicians – Debsy from Saint Etienne and Gus from The Gurgles – who will illustrate with parts of the songs.”

The lost legends who made the world go pop

Kay Swift

She was a classical musician until she met George Gershwin in 1925, with whom she had a long affair. She began writing popular music and was the first woman to score an entire Broadway musical.

Swift collaborated with her husband, lyricist and lawyer Paul James, and together they wrote hits like Can’t We Be Friends, which would end up on Sinatra’s In The Wee Small Hours album and Ella Fitzgerald’s Sweet Songs For Swingers, and Can This Be Love.

She later eloped to Oregon, moving to a ranch and writing the memoir Who Could Ask For Anything More?, which was turned into a Hollywood musical called Never A Dull Moment, with Irene Dunne playing Swift.

Lee Morse

Stanley writes that Morse had the “sleepy-eyed looks of Bette Davis and the sound of a more tuneful Mae West”. Her voice was so deep that earlier recordings credited her as Miss Lee Morse.

She often accompanied herself on guitar, ukulele and kazoo and wrote a lot of her own material, such as There Must Be A Silver Lining and Be Sweet To Me.

She was a star in the 1920s but spent the following decade performing in small nightclubs, hindered by alcohol.

Whispering Jack Smith

Smith was said to have gained his nickname after a First World War German gas attack left him with a limited vocal range. After the war, he worked for Irving Berlin’s publishing company by day.

But, when the radio industry informed Tin Pan Alley that a range of no more than five melody notes suited the limited capabilities of radio broadcasting, his voice was ideal in comparison to bellowing vaudeville voices.

He was a natural crooner and had hits with Cecilia, Baby Face and Me And My Shadow, before falling out of favour.

John Hill Hewitt

Stanley describes Hewitt as “the first truly American songwriter, and one not scared to write about current affairs”. He wrote popular songs in the 1820s, such as The Minstrel’s Return’d From War, which was about a soldier torn between his girl and his country.

He wrote more than 300 songs and was a music teacher at seminaries for women, as well as working as a theatre manager, concert performer, and magazine and newspaper editor.

Let’s Do It: The Birth Of Pop is out now on Faber

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe