To love my body is something I struggled with for years – and I’m shocked that it took a medical emergency to achieve it. I have been weighing and measuring myself since I was a child, always finding fault and wanting to lose five pounds, 10 pounds, a stone – and I was still in that mindset in 2019 when I was diagnosed with breast cancer aged 54.

The shock of the diagnosis was total and sent me into a spiral of terror. It had come out of the blue following routine breast cancer screening – there was no pain, no lump, no sign at all that anything was wrong. And yet here I was facing a life-changing crisis. I realised immediately how much I had taken my health for granted. I was born on a farm in Lancashire during the era when children were seen and not heard and where “being poorly” was barely tolerated. The attention went on the animals not the humans – humans just got on with it.

But I do remember my mother always struggling to lose two stones. She would make the family delicious home-cooked roasts, pies, and puddings while she munched on slimmers’ crispbreads. I got used to wondering exactly how fattening certain foods were, and when I asked her she would reply ominously: “All foods are fattening, Catherine.”

My grandma would visit and insist on sweeteners in her tea because she was also trying to lose a stone. Neither of these two women ever managed to achieve their elusive weight-loss – or at least not until first my grandmother, followed by my mother, succumbed to cancer and the weight dropped off them unbidden.

I joined my first slimming club aged 19 and a size 10. I queued up in a dusty community centre to be weighed in, whereupon I was told that I was nine and a half stone and had “only just arrived in time”. I was put on a diet that relied on packaged convenience foods – this was 1982 – and every week if I had gained rather than lost weight, the club leader would stick a picture of a fat pink pig in my weighing-in book.

I didn’t realise how ludicrous this was – being encouraged to live on Batchelors Cup-a-Soup and Birds Eye Liver with Onion and Gravy while paying to be insulted at a slimming club, when my body was fit and healthy (and, incidentally, already slim).

Life continued for decades with other slimming clubs, gym memberships (for weight loss, not fitness) “going for the burn” Jane Fonda-style, obsessive calorie counting, nights out nursing a Slimline Orange. “Low calorie” this, “lite” that, “reduced fat” the other – life with the fun taken out.

Not only that but I’d wear high-heeled shoes come hell or high water – to run for the bus, to do the supermarket shop – I went nowhere in flat shoes because high heels were “slimming”. Never mind that my feet were so used to stiletto heels it became painful to walk barefoot.

Underwear was uncomfortable too – there to constrict and control, regardless of how much it dug in or stopped me breathing properly. Underwired bras and industrial-strength elastic knickers were not too far away from the corsets and girdles that had controlled my mother and grandmother.

I hit an early menopause at 42 and the weight became even harder to keep off – more Slimming World, more Weight Watchers, more calorie counting and food tracking to avoid the terror of not only getting fat but getting old.

Then came the cancer diagnosis and I was faced with surgery, radiotherapy, and years of hormone therapy. The treatment was harrowing – despite me being lucky enough not to need chemo. I felt like I had aged 20 years in a few months, I was exhausted and traumatised and suddenly realised that my body needed to be cared for, not starved, constricted, and judged – only to be found wanting.

All those years of criticism and my body had been quietly doing its job – and quite well too – and now it needed my help to get back to good health. I started taking better care of myself – religiously using the skin creams to stop radiotherapy burns, resting often to ease the treatment fatigue, wearing loose, comfortable clothes and sleeping in silk pyjamas to help deal with the fierce drug-induced hot flushes, and always wearing trainers to make it easier to take daily walks for exercise.

I took advantage of the complementary therapy offered by Macmillan Cancer Support – enjoying sessions of the Bowen technique, to the scent of essential oils, with their lovely therapist. Just being in the presence of complementary therapists made me feel cared for.

I upped my yoga, from one session a week to three. Previously I had done yoga for vanity reasons – now the classes became the perfect place to do some deep breathing, gentle stretching and to concentrate on how my body was feeling.

Edinburgh City Council, together with MacMillan, offered free exercise classes to people recovering from cancer, so every week I did gentle circuit training at Meadowbank Stadium. Class members ranged from old to young but the music was from my era – and I felt a surging joy as I leapt from foot to foot, bending and stretching, to the Bee Gees and Elton John.

The trees were just coming into bud outside, it had been a long, cold, lonely winter and now it was a chance for a fresh start – a chance to have another go at life a bit differently. I sang along to the music and realised that this was the first time I had exerted myself in a gym to feel strong rather than to use up calories and feel thin. I was interested in what my body could do, not just what it looked like.

Not only that, but the classes were an opportunity to chat with other people who had gone through similar traumatic experiences to myself. The Moving Forward course offered by Breast Cancer Now was similar and helped to reduce the sense of loneliness and fear that can linger after a cancer diagnosis.

I saw for the first time that the obsessive worry, guilt, and shame around food that had wasted so much of my time and energy over the years was wrong – food is in fact a friend, not an enemy, a source of pleasure and nourishment, not of stress and panic. The aim of life cannot be to die thin and hungry. I was determined to enjoy every single mouthful I ate from now on and never to choose meals based on calorific value.

Since my recovery, I go back every year for a mammogram to check that there is still no evidence of cancer. I nearly didn’t go for that first mammogram back in 2018 because I was a bit scared and I thought it was unnecessary – when in fact it saved my life.

Ageing is a privilege. Having lost a sister aged 46, I know it is the lucky ones who get old. Good health is another great privilege. Cancer made me want the privilege of ageing healthily, not ageing “youthfully” by trying to deny the ageing process.

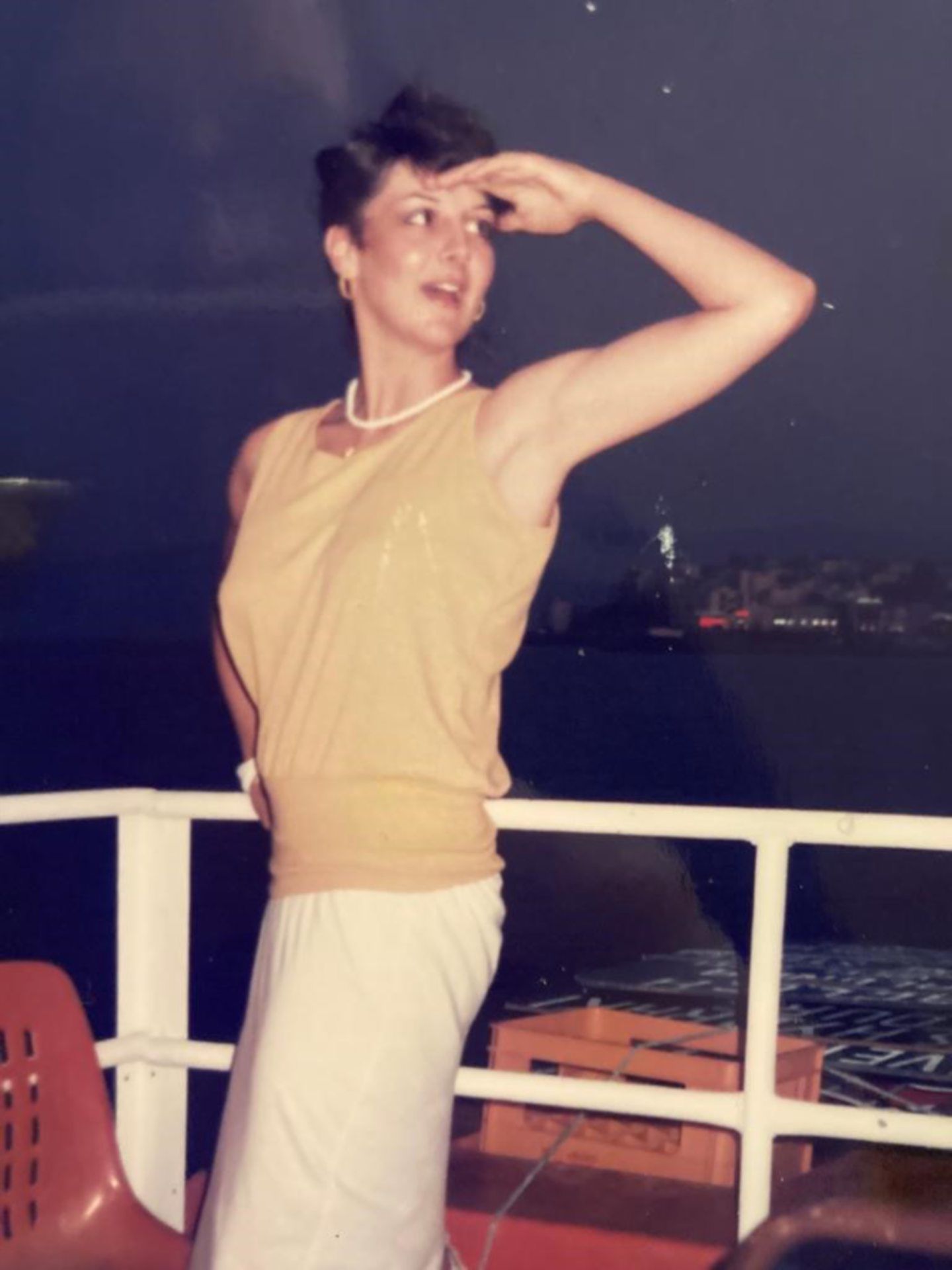

One Body: A Retrospective by Catherine Simpson, published by Saraband, is out now

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe © SYSTEM

© SYSTEM © SYSTEM

© SYSTEM © SYSTEM

© SYSTEM