For years he didn’t think about him. Now he can’t stop.

Every night Eddie McColl, 75, says he remembers his kid brother Francis, who died at the age of 13. Both siblings, along with older brothers John and Willie, were taken from their widowed mother, Ellen, in the early ’50s. After coalman dad John died from tuberculosis, the family had been left on its uppers.

Eddie remembers being so poor, he would raid bins for clothes to wear to school in the tough area of Maryhill in Glasgow. Soon, the three younger brothers were taken to Smyllum Park orphanage in Lanarkshire to be protected and cared for. Or so they hoped.

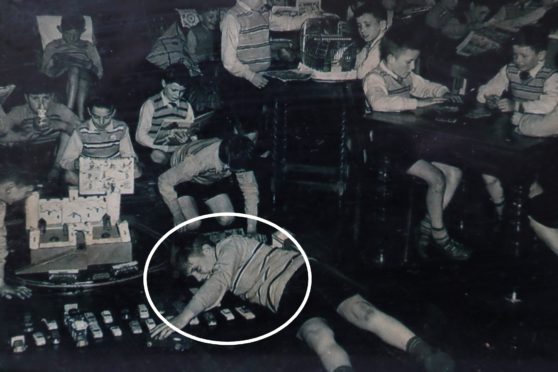

In 2018, the Scottish Child Abuse Inquiry heard evidence that the orphanage – run by the religious order of nuns, the Daughters of Charity – was rife with physical and sexual abuse suffered by many of the children taken there.

John, a streetwise teenager, escaped life at Smyllum, originally running away before being allowed to live with an aunt. Francis, the youngest and not yet at school, was kept away from his brothers in the nursery wing.

“We just didn’t see him. He was in the nursery and we were elsewhere, going to school,” said Eddie. “We used to sneak in and see him but families were kept apart in Smyllum.”

By the end of the ’60s, two of the brothers were gone. Francis, the youngest, deaf in one ear, died at 13.

By that time, both Eddie and Willie had left Smyllum but Francis was still there having spent almost all of his life under the nuns’ care.

In the summer of 1961 he was hit on the head by a golf club. A day later, he was taken to hospital. He never came out. The Procurator Fiscal concluded Francis’s death, on August 14 due to complications from head trauma, was an accident.

John, who moved to Australia soon after Francis’s passing, would die in a drowning accident there in 1967. The next four decades saw Eddie join the army, marry Patricia and have three children and then grandchildren.

By the early 2000s his meet-ups with older brother Willie were regularly turning to talk about Francis and their childhoods in Smyllum.

“By then it was clear what had happened at Smyllum wasn’t normal. The abuse, the fear,” said Eddie.

“There was a growing number of people like us who were starting to say, ‘hang on, that wasn’t right’. Smyllum Park had a reputation even when we went in. I think that’s why John ran away and wouldn’t stay there. I remember him turning up on an old motorbike to get us for days out and telling the nuns they better not touch us.”

Emboldened by changing attitudes towards past childhood abuse, Eddie and Willie began asking questions about Francis, including where he was buried. Incredibly, it had never been established what had happened to his body, leaving his surviving brothers unable to visit his final resting place.

The Daughters of Charity said it couldn’t help. Nor could nearby Catholic churches.

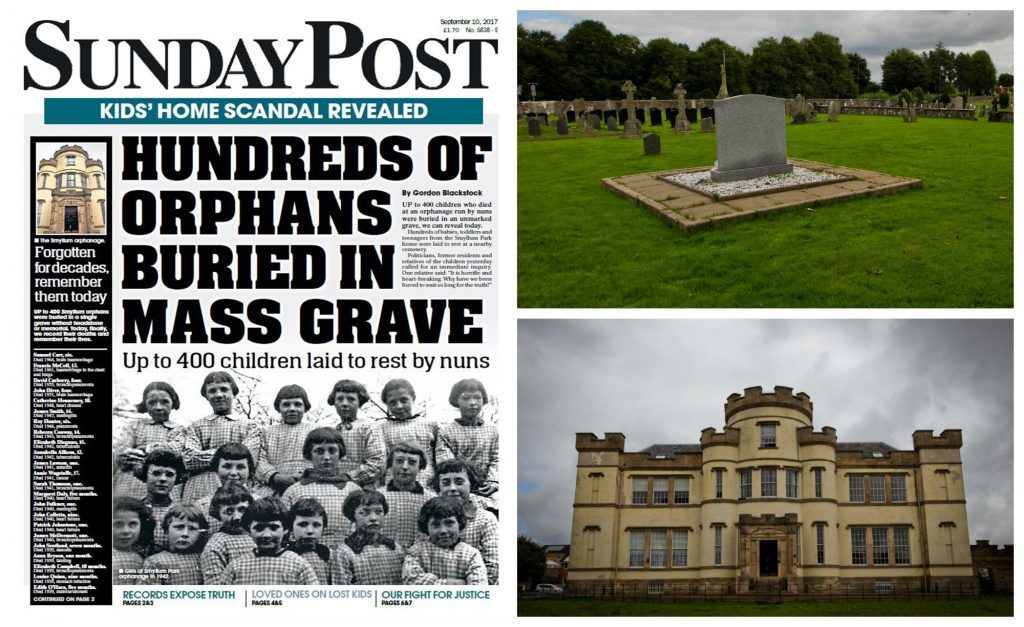

In 2017, The Sunday Post and BBC Radio Four’s File on 4 carried out an investigation revealing 400 other deaths like Francis’s at Smyllum Park orphanage. Almost all were feared to have been buried in unmarked graves at St Mary’s cemetery near the home.

Expensive, black marble gravestones, paid for by the Daughters of Charity, marked the burial of nuns nearby. The contrast couldn’t have been starker and our story provoked widespread anger and promises of action from the Daughters of Charity, whose representatives would be asked to give evidence to the abuse inquiry months later. The order said, via a London-based PR agency it had hired to handle the fall-out from the scandal, that it was committed to finding out how many children it had put in unmarked graves in St Mary’s and to erecting a memorial naming them all.

Researchers were hired and deadlines pencilled in. But then it went quiet.

Privately, the Daughters of Charity told survivor groups that a memorial naming all the children might not be possible due to fears some names would be missed out. Months turned to years. Then, in 2019, Willie died without receiving the answers he’d craved.

“It just seemed to be business as usual,” said Eddie. “The head of the order, Sister Ellen, cried at the Scottish Child Abuse Inquiry when giving evidence.

“I hoped her attitude would make a difference but it all went quiet again.”

Come the start of this year, Eddie decided he’d had enough of waiting. He wrote to Sister Ellen pleading for answers.

He began: “I am writing to you in an effort to finally receive answers to what happened to my brother Francis’s body after he died. I am now 75 and in advancing years.

“I think the Daughters of Charity owe me the opportunity to be able to pay my respects at my brother’s graveside before I pass away. I am sure you agree, I saw how much you were affected by remorse over what a few of your unscrupulous predecessors did when you gave evidence at the Scottish Child Abuse Inquiry.

“Please give me the answers I am looking for.”

But the reply from Sister Ellen, whose £16 million-a-year charity now runs care homes rather than orphanages, admitted she still didn’t know what happened in Francis’s case. It is also unclear what steps, if any, the order has taken to try to find out. The only research her reply referred to were facts established at the SCAI, many first reported in The Sunday Post.

There was no mention of the team of researchers it claimed to have instructed.

In her reply, Sister Ellen asked if older brother John, who had signed the death certificate, might be able to help. Eddie described her response as indicative of an organisation which has never given him answers.

“John died in 1967. He wasn’t Francis’s carer – they were. Why on earth weren’t his burial records recorded by them? They either don’t know or don’t want to say how many kids are buried at St Mary’s,” said Eddie.

“The only thing Sister Ellen knows about my brother was what was printed in The Sunday Post two years ago.

“My life has been bookended by Smyllum. My childhood was spent getting tortured there mentally and physically. And now at the end, I’m going through the same mental torture again over what’s happened with Francis. Why can’t they help?”

The Daughters of Charity said: “The research is well under way, but unfortunately it has taken much longer than expected to work through – it is painstaking, and many records are incomplete or missing altogether.

“Nevertheless, we should be in a position to report back some time in the summer.”

Eddie hopes the organisation will finally come good on their word.

“I’m the last brother alive, I just hope to live long enough to find out,” he said.

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe © Stewart Attwood Photography

© Stewart Attwood Photography