It was once the crown jewel of Scotland, an item of huge religious significance revered by the kings and queens who possessed it, worshipped it, fought over it and even died grasping it.

For centuries, the Black Rood – an ornate and bejewelled golden cross-shaped reliquary containing a supposed piece of the True Cross – existed as a symbol of an independent Scotland, bearing as much importance to monarchs as the Stone of Scone.

Yet, having been seized by King Edward I of England, it disappeared around 1590; lost to time, history and collective memory. Also referred to as the Holy Rood, it still resonates in the name of Edinburgh’s famous park, home to the Scottish Parliament. However, the whereabouts and fate of the Black Rood remains a mystery.

Now, following eight years of research, historian David Willem is trying to shed light on this lost relic in his new book Black Rood: The Lost Crown Jewel Of Scotland.

The historian also learned of a Welsh reliquary of the True Cross called Y Groes Gneth, which had a similar history to the Black Rood, and an Irish one, the Cross of Cong. His book examines this triumvirate of crosses, which all conferred divine power and status on their possessors, and were coveted by invaders due to their shared religious and political significance. The first reference to the Black Rood is in 1068 when Saint Margaret brought it to Scotland two years before she married King Malcolm III. Both the fragment of the True Cross and the reliquary that held it were referred to as the Black Rood or Holy Rood.

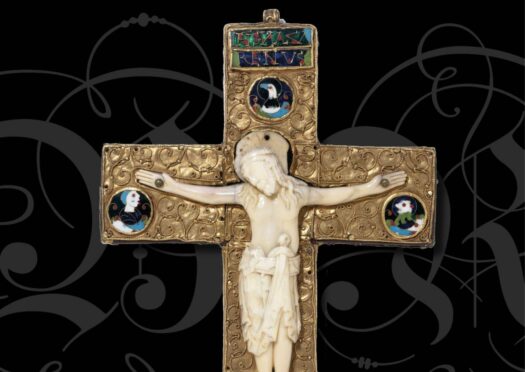

“It is first described as a gold and jewel encrusted reliquary in the shape of a crucifix, probably the length of a palm, which opened and closed like a box. It was made of solid gold, adorned with golden ornaments and bore an ivory statuette of Christ. Inside it contained a piece of the True Cross,” explained Willem.

“It was impressive, very precious, and very personal for Queen Margaret, who may have worn it and is said to have clutched it to her on her deathbed. In medieval times a reliquary of the True Cross was a symbol of sovereignty, so her youngest son, David I, later turned it into a Scottish crown jewel.”

Willem first heard of the cross after writing about the relics of Saint Cuthbert found in his tomb in Durham Cathedral in 1827, including a gold and garnet cross dating back to 698. He learned that other Anglo Saxon crosses had been kept in the cathedral, including the Black Rood, which disappeared during the Reformation.

For Willem, the name “Black Rood” suggests the part of the True Cross it allegedly contained had been possessed by Margaret’s ancestors for a long time.

“Rood is an old word for rod or cross but black doesn’t make sense for a golden, opulent reliquary,” he said. “However, what’s interesting is that Margaret was an English princess of House Wessex, and King Alfred of Wessex received a piece of the True Cross in 883. In old English (Anglo-Saxon), the word black actually meant shining so it’s possible that this contained a very old portion of the True Cross going back in that family to 883.”

Queen Margaret’s son, David I, who claimed the Scottish throne in 1124, shared his mother’s piety and founded Holyrood Abbey in Edinburgh in 1128, most likely as a place to house the Black Rood.

David I also died reportedly holding the Black Rood like his mother. The relic passed down the royal line for 200 years until King Edward I of England intervened during the crisis of Scottish succession and later invaded Scotland in 1296. Once in his possession, the meaning of the Black Rood shifted from a cherished marker of Scottish monarchs’ power and divinity to a symbol of oppression.

“When Edward I takes the Black Rood and the Stone of Scone, he treats them as of equivalent importance because, for him, it symbolizes the independence of Scotland,” Willem explained.

“Edward thought it was important enough to take it and to keep it personally. He didn’t send it to Westminster Abbey, like the Stone of Scone. He kept it in his private chapel, along with the Welsh cross that he also obtained.”

Edward even used the Black Rood to extract oaths of loyalty from Scottish clergy, nobles and soldiers. Yet the crowning of Robert the Bruce as King of Scotland saw the significance of the Black Rood as a symbol of Edward’s dominance over Scotland diminish.

Following the king’s death, details of what happened to the Black Rood become hazy until it ended up in Durham Cathedral following Edward III’s victory over the Scots at the battle of Neville’s Cross in 1346.

“It was in Durham Castle up until 40 years after the reformation, when it was supposed to have been handed over to Cromwell and Henry VI. The last reference in 1509 doesn’t quite fit with previous descriptions,” said Willem.

So what became of the Black Rood? With no further documented references to the relic, historians can only theorise. It could have been destroyed, broken up with its jewels and ornaments turned into jewellery, buried or even hidden away like the Cross of Cong to be found centuries later.

Made in the 1120s, the Cross of Cong had a transparent rock crystal at the centre of the Cross, which magnified the piece of the True Cross within. Yet it disappeared from records apart from one reference until the late 18th Century. Willem explained: “William Wilde, Oscar Wilde’s dad, first came across it as a boy when he spotted it in a local Abbot’s cottage, kept it in a cupboard. The Abbot had found it somewhere in the village of Cong. It was eventually given to the National Museum of Ireland, where it is still on display.”

Whatever its fate, what is certain is that the Black Rood would remain a potent symbol of sovereignty and independence today.

“These objects connected the rulers who held them to the authority and status of Rome, and back to Jerusalem and the crucifixion, and demonstrated to the world that their kingship had the favour of God, so they were very powerful statements about legitimacy and sovereignty,” said Willem.

He hopes that by making more people aware of the Black Rood, more clues to its fate or whereabouts could be unearthed.

“The idea is to highlight the possibility that the Black Rood, this crown jewel that defined the sovereignty of Scotland through the medieval period, still exists somewhere. It could have been hidden away by the Catholic community and has perhaps been kept somewhere, its name and meaning long forgotten,” he added.

“There’s no record of it being broken up like the Welsh Cross so it’s intriguing. Things turn up all the time, like the Cross of Cong, so it could be out there somewhere waiting to be discovered.”

Black Rood: The Lost Crown Jewel Of Scotland is published by Whittles

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe © SYSTEM

© SYSTEM