They are official reviews that are often called for in the wake of tragic accidents, disasters or large-scale failures of government or public services.

And to many, including victims, experts, campaigners and, indeed, newspapers like this one, they are seen as vital in understanding what went wrong and in helping to prevent the same mistakes from happening again.

But as the Scottish Covid Inquiry gets under way, concerns have been raised about the costs of such reviews and fears voiced over how long they take to report back.

Families of Covid victims hope this latest public inquiry will finally provide the answers they have been calling for, but some fear issues around accessing key information could lead to further frustration.

The probe, which had its first hearings this week, is expected to continue until 2025. Figures released in July showed the bill for the inquiry had already reached £8 million – despite public evidence sessions still being months away at that point.

Meanwhile, the UK Covid Inquiry – which is separate to its Scottish counterpart but includes Scottish Government officials – has already been beset by issues.

Covid lawyer Aamer Anwar says missing WhatsApp messages could be a ‘treasure trove’

A leading lawyer representing families of people who died during the pandemic is calling for answers on why messages were routinely deleted by senior government figures and advisers. Aamer Anwar, lead solicitor of Scottish Covid Bereaved, said it is inconceivable that those tasked with managing the crisis failed to retain communications – particularly after it became clear as early as 2021 that an inquiry was to be held.

He wants to know whether an order was made from the top to delete chats on private messaging services such as WhatsApp and Telegram, who made it, when, and why it was not abandoned for the sake of the looming investigation.

His call comes following reports that national clinical director Jason Leitch deleted messages every day during the pandemic.

Anwar said he met with government officials, including former Deputy First Minister John Swinney, as early as August 2021 to stress the importance of retaining the information. The UK Government was unsuccessful in a court bid to block the disclosure of communications between Boris Johnson and others to the UK Covid inquiry.

Meanwhile, the Scottish Government has failed to turn over a single message from SNP ministers or officials. Anwar said: “The Cabinet Office went to war over these messages and it lost that war. Those messages were an absolute treasure trove that exposed the incompetence, panic and territorial conflicts at the heart of government.

“At times it looked like a fight in a nursery. It begs the question, why should it be any different for Scotland? The Scottish Government promised families transparency. We find it inconceivable that senior government figures and medical advisors failed to retain this material.”

The UK Covid Inquiry’s legal team believes the majority of WhatsApp messages shared among Scottish Government officials during the pandemic have not been retained.

With all this in mind, The Sunday Post looks back over some of the biggest Scottish public inquiries, how much they cost, and the impact they had on those affected.

Edinburgh trams

Alex Salmond, then the first minister, announced in 2014 an inquiry into why a project to construct new tram lines in Edinburgh was finished five years late, ran £375 million over budget and delivered a significantly shorter route than initially planned.

The inquiry faced its own long delays, with costs rising to more than £13m – more than the Chilcot Inquiry into the Iraq War – before it finally reported back in September this year.

It was reportedly described by a source involved in the tram service as a “bigger scandal than the one it was set up to look into in the first place”.

The report concluded that failings by City of Edinburgh Council and its arm’s-length organisations were largely to blame for delays in completing the tram lines.

The SNP, who wanted to scrap the project but did not have a majority at Holyrood, were also criticised for scaling back Transport Scotland’s involvement, meaning important safeguards were removed.

Lord Hardie, who chaired the inquiry, was not available to answer questions from the media about why it took so long and its overall cost.

He set out 24 recommendations, including consideration of new laws that would allow civil and criminal punishments for those knowingly submitting reports with false statements to local authorities.

Scottish Parliament building

A probe into the building of the Scottish Parliament was ordered by then first minister Jack McConnell in 2003 after the building was delivered three years late and for 10 times the original budget, at £414.4 million.

Audited accounts for the inquiry published by the Scottish Government revealed it cost the taxpayer £717,426.

That included £127,659 in fees for Lord Fraser, the Tory peer who conducted it.

Evidence was collected over the course of 49 hearings, with Lord Fraser later saying he was astonished that ministers were unaware of rising costs during the project.

He also said it was his belief that the building could never have been built for the original budget, and it should have been clear from at least April 2000 that it would cost in excess of £200m.

About £150m of the final cost was wasted as a result of design delays and bad management of the project.

The Scotland Office was heavily criticised for pushing contractors to finish the building early, without considering how this would impact on the final cost.

McConnell accepted all of Lord Fraser’s recommendations in the report and carried out what he described as a fundamental reform of the civil service in response.

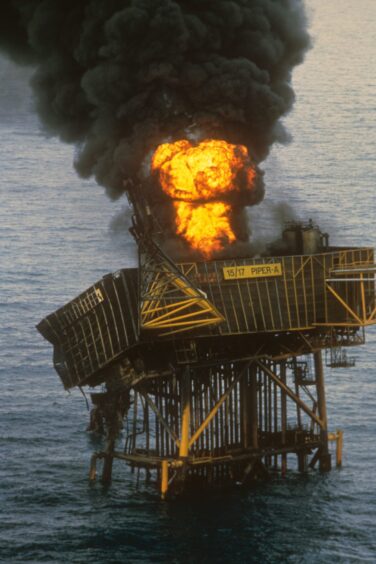

Piper Alpha

Piper Alpha, an oil platform in the North Sea, exploded and collapsed in July 1988, killing 165 of the men on board and a further two rescue workers.

The Cullen Inquiry, set up in November 1988 to establish the cause of the disaster, led to 106 recommendations that transformed the Scottish oil and gas industry into a global leader in safety.

The UK Government admitted in 2013 that it had no idea how much the 13-month investigation into the world’s worst offshore disaster actually cost.

Then-UK energy minister Michael Fallon said the government was unable to locate any documents showing how much taxpayers paid for the probe.

The inquiry was critical of Piper Alpha’s operator, Occidental, which was found guilty of having inadequate maintenance and safety procedures.

However, no criminal proceedings were ever brought against the company.

The recommendations in the report led to the Offshore Safety Act 1992 and the making of the Offshore Installations (Safety Case) Regulations 1992.

Survivors and relatives of those who died continue to campaign on North Sea safety issues.

Dunblane

The murder of 16 school pupils and one teacher at Dunblane Primary School in 1996 remains the deadliest mass shooting in British history.

The aftermath of the massacre saw a public outcry over gun-control laws that led to the 1996 Cullen Report.

It was carried out by the same peer, Lord Cullen, who conducted the Piper Alpha inquiry and consisted of 26 days of oral evidence and a large number of written submissions.

The report recommended the introduction of tighter controls on handgun ownership and that the government should consider whether an outright ban on private ownership would be in the public interest.

It also recommended changes in school security, specifically vetting of people who work with children.

Following the killings, two new Firearms Acts were passed which outlawed the private ownership of most handguns in England, Scotland and Wales.

Since the new legislation was brought in, no mass shooting with handguns has occurred in Scotland and incidents involving lawfully owned firearms remain rare.

The Scotland Office was asked to confirm the cost of the inquiry but did not respond.

Penrose

The Penrose Inquiry was launched in 2008 to look into the contaminated blood scandal and cost more than £12 million.

It investigated hepatitis C and HIV infections from blood used by NHS Scotland to treat people with conditions such as haemophilia.

It took six years to return its findings and has been strongly criticised by victims.

At a press conference to accompany the publication of the report, members of the audience could be heard shouting allegations of a whitewash and cover-up.

It did not apportion blame and made only one recommendation – that blood tests should be offered to anyone in Scotland who had a transfusion before 1991.

Lord Penrose was reportedly too ill to attend the publication of the findings.

Following the publication of the report, then-prime minister David Cameron issued a formal apology for the scandal.

A full UK-wide inquiry was ordered in 2017, with a court ruling the same year finding in favour of the victims and allowing them to launch High Court action to seek damages.

It was announced last year that an interim compensation payment of £100,000 would be paid to each victim.

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe © PA

© PA © PA

© PA © PA Archive/Press Association Images

© PA Archive/Press Association Images