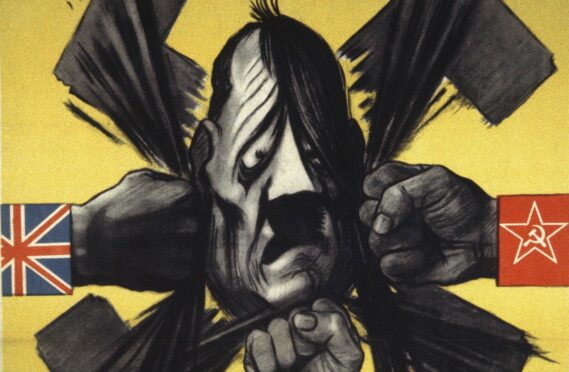

For thousands of years, the simple four-legged symbol was carved into doorways, stone walls and pottery to promote wellbeing and good luck. It took just one man and his hateful ideology to change its meaning forever.

Traditionally associated with the peaceful religions of Hinduism and Buddhism, the first documented use of the swastika was around 18,000 BCE, and its hooked harms have been used by cultures around the world, from northern Europe to eastern Asia and Africa. However, when Adolf Hitler adopted the emblem for his Nazi party in the 1920s, the symbol’s previous history was erased.

“Like other symbols, the swastika became associated with a short period of use, with the loss of a much longer history,” explained author Colin Salter. “Abhorrent acts were committed under the new German flag, a black swastika in a white circle on a red background, driven by xenophobia and anti-Semitism, plunging Europe and the world into a second world war. After the war, the use of the swastika and other totalitarian iconography was banned in many European countries including Germany and Austria.

“The swastika had thousands of years of history as a positive thing, and then 25 years of Adolf Hitler meant it was ruined. The same thing could happen to any symbol.”

Easily identifiable and loaded with symbolism, the swastika is just one example of the icons, pictographs and logos that have shaped our world, enabling us to communicate without words.

In his new book, 100 Symbols That Changed The World, Salter takes readers on a journey through time, detailing in chronological order the genesis and adoption of the world’s most recognisable signs. Beginning with the swastika and ending with the hopeful rainbows of the pandemic and the LGBT community, each motif, whether used by ancient civilisations or modern corporations, has a hidden power.

“Symbols are instruction or advice on how to live our daily lives, and I think that’s fascinating,” said the Edinburgh-based writer, who first became interested in symbols while studying design and applied arts. “One cannot escape historic symbolism – little things often represent much bigger things. Plus, we’re tribal people, and the things that define us as one or the other – even having an iPad or an Android tablet – have symbols that unite and also divide.”

The most recognisable, and therefore effective, symbols in use throughout the world, Salter said, help us to know where we belong, where we are going and what to do (or not do) when we get there. Often older than language itself, many traditional logos borrow from mythology or religion, and are therefore able to instantly communicate a universal message.

Historic symbols, Salter explained, tend to be “very useful, clear and explicit” and use only pictograms to be easily and universally understood.

One example is the Rod of Asclepius, which since around 450 BCE has been used as part of the insignia of medical institutions, including the World Health Organisation. A wingless rod with a single snake wrapped around the body, it is thought to represent Asclepius, son of the sun god Apollo, who had the secrets of healing whispered into his ear by a snake.

Salter said: “Even if the original common knowledge is lost, we still understand such symbols, and the snake is a very good example. We all recognise that as a health symbol now, although we have probably all forgotten the original Greek legend it comes from.”

However, not all signs adopted from mythology stand the test of time. “Traffic signs have gone through a lot of changes since they were first introduced at the beginning of the 20th Century,” said Salter.

“We’ve gradually figured out what works and what doesn’t, and the right kind of clear lettering to use – although we were really quite devoted to gothic script for a long time, and if you were tootling along trying to make out the letters of a sharp bend, chances are you would have missed it.

“One of my favourite traffic symbols is the British symbol for schools, which is now a triangle with kids running across. But it used to be – and this is so very British – a flaming torch.

“It was a very pretty symbol, but if you didn’t know that the torch is a symbol for learning, the flaming power of knowledge burning brightly, how would you know what that represents?

“That symbol was in use from about 1920 onwards and only in 1965 did they think, you know, maybe we could have a much more clear indicator that you might kill a child if you go around this corner too fast! There’s a lot of tradition in iconography.

“Level crossings today, for instance, are still indicated by a steam train because it’s much easier to recognise a steam train than it is a boxy two-car ScotRail Express. The really good symbols are pictographic because we still understand those best of all.”

While many of the symbols Salter explores have deep-rooted, almost innate meaning – like, for example, the tree of life or the Christian Ichthys – his favourite remains unreadable. “Pictish symbols are really quite unusual because we don’t know what they mean,” explained Salter of the carvings, which appear on hundreds of monoliths around Scotland, and are the only historical evidence of the Pict people, who lived from 200 to 900 CE.

“They are exquisite and also tantalising. I will never forget the first time I visited a Pictish standing stone up somewhere in Angus, just sitting in the middle of a field.

“It’s very exciting to think there was an entire people and we have no written record of their lives. I’m fascinated by them. There has been a renewed interest in the Picts because of the new confidence that Scotland has as a result of devolution, and because of that, research is racing ahead.”

Colour, shape, iconography and history all play a role in the most successful symbols and logos (Apple’s half-eaten fruit logo, according to Salter, stands out because “a four-year-old has probably seen it more often than they’ve seen the Christian cross or some traffic symbols”) and in our modern “age of symbols” this has never been more apparent.

“Our whole lives are on our phones and it’s all channelled through icons,” Salter said. “We communicate in emojis now, and it’s almost a logical conclusion of everything that’s gone before – suddenly now, here we are, living our entire lives almost without spelling, but with icons instead.”

No words necessary

They are some of the most iconic symbols in use today, each with a fascinating backstory spanning decades or even centuries.

As featured in Colin Salter’s book, here are the stories of nine of the most familiar and interesting signs.

Musical notation

The oldest genuinely complete piece of recorded music is known as the Seikilos epitaph. Carved on a stone column memorial found in western Turkey near Ephesus and dedicated to a man named Seikilos, it is dated to between 100 and 200 CE. It bears a poem about the fleeting nature of life written in Greek, with the notes chiselled above the words. The notes are shown by letters, in a system devised by Pythagoras some 700 years earlier, with further abstract symbols beside them giving other instructions.

Maltese Cross

The Maltese Cross is the least cross-like of the many “cross” symbols, more like a star or a flower than a cross. Its four arms do not in fact cross at all but converge like arrows on a bullseye. Its origins may lie elsewhere but its connection to the island of Malta is historic and unbreakable.

Poppy

When Canadian medical officer Lieutenant Colonel John McCrae lost a close friend on the battlefield of Ypres during the First World War, he expressed his grief in a few short lines of poetry. The poem, in today’s terms, went viral, inspiring a symbol of loss and commemoration.

Evil Eye

The use of a symbolic Eye to ward off evil became a more general practice to avert misfortune. Ships in the ancient cultures of Greece, Egypt and China are all known to have been decorated with eyes. Even today, Turkish airline Fly Air decorates its tailfins with a nazar boncugu, a blue Evil Eye charm.

The Smiley

One of the most recognisable and flexible of symbols, the Smiley face has taken on many different meanings in the years since its creation in the 1960s. From the Peace movement of the 1960s through the high-energy dance culture of the 1980s, the Smiley has evolved into an entire language of emotional expression.

Windows

The history of Microsoft’s Windows symbol is a case study in small changes. In essence it has remained the same since Windows was launched – a window with four panes – but little adjustments with each new release have, over time, made the latest version very different from the first.

Astrology signs

The symbols may seem meaningless at first glance, but many are simply abstracted pictograms of their subjects. Aries, the ram, is represented by a stylised pair of horns. Capricorn, part-goat, part-fish in Babylonian culture, has a ram’s horns and a fish’s tail. Leo the lion is a face with a flowing mane. Scorpio has many legs and a sting in the tail.

The Jolly Roger

The skull, with or without crossed bones, has been a recorded symbol of death since at least the 6th Century when it began to appear on grave markers. It was a reminder that death – the Great Leveller – comes to us all. The first recorded use of the flag is by pirate ships on the notorious Barbary Coast of northern Africa. These ships raided ports not only there but in Europe.

Anarchy

A is for Anarchy in many languages. Although the concept of anarchy is often misunderstood, there’s no mistaking the simple symbol of an A in a circle, as adopted by nihilists, punks, students and anarchists all around the world.

100 Symbols That Changed The World is available now.

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe