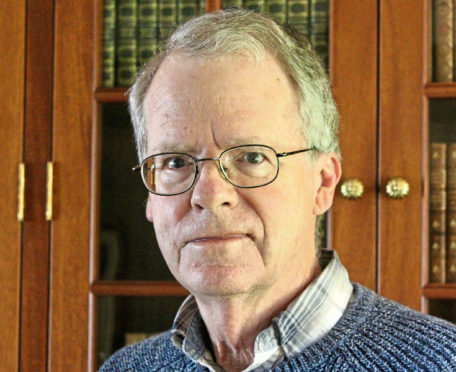

For most people, an Alzheimer’s diagnosis would be devastating. But Dr Daniel Gibbs is not most people – he’s a neurologist who has specialist understanding of the condition, and also has early-stage Alzheimer’s himself.

While he admits he’s “disappointed” to have the disease, Gibbs says he’s “fascinated” by it. He stumbled upon his diagnosis 10 years ago, before he developed cognitive symptoms (Gibbs took a DNA test to trace his ancestry, which revealed genetic links to Alzheimer’s). This gave him the chance to tackle it very early on.

“It’s easy to say I’m unlucky to have Alzheimer’s,” says Gibbs. “But, in truth, I’m lucky to have found what I found, when I found it.”

As a result, the American neurologist, now 69, has devoted his life to researching the disease and what can be done to slow its progress. He’s explained his findings in a new book – A Tattoo On My Brain: A Neurologist’s Personal Battle Against Alzheimer’s Disease – that reveals the lifestyle choices Gibbs, and many in the dementia community, believe can help slow the progress of Alzheimer’s, particularly in its early stages. And by “early” he means before symptoms (there can be changes in a brain with Alzheimer’s up to 20 years before there are any cognitive signs, Gibbs points out).

Gibbs started getting cognitive symptoms nine years ago, when he began having problems remembering the names of colleagues, and retired soon after. He now has increasing problems with his short-term memory, often can’t recall what he did an hour ago, and needs to write down plans and keep a calendar. Still, he insists: “Most people would have no idea I have Alzheimer’s.”

Gibbs believes the lifestyle modifications he’s made since his diagnosis have helped slow the progression of the disease, and says such lifestyle measures also appear to reduce the risk of getting Alzheimer’s in the first place. “The important message is all of these modifications are likely to be most effective when started early, before there’s been any cognitive impairment,” he says.

“The pathological changes in the brain that result in Alzheimer’s begin years before the onset of cognitive impairment – up to 20 years for the amyloid plaques. Once nerve cells in the brain start to die off and cognitive impairment begins, lifestyle modifications seem to have less, if any, impact.”

Gibbs says the same is probably true for drugs, adding: “The time to intervene, both with lifestyle modifications and with potential drugs, is almost certainly early, before significant cognitive impairment has occurred.”

Dr Tim Beanland, the Alzheimer’s Society’s (alzheimers.org.uk) head of knowledge, agrees healthy lifestyle measures are thought to help slow the disease’s progress.

“There’s growing evidence to suggest regular exercise, looking after your health, and keeping mentally and socially active can help reduce the progression of dementia symptoms,” says Beanland.

“We know that what’s good for the heart is good for the brain, so a healthy diet and lifestyle, including not smoking or drinking too much alcohol, can help lower your risk of dementia, and other conditions like heart disease, stroke, diabetes and some cancers.”

Here, Gibbs outlines six steps to help reduce the risk and slow the progress of Alzheimer’s in its very early stages…

1. Exercise

There’s overwhelming evidence regular aerobic exercise reduces the risk of Alzheimer’s and slows the progression of the disease in the early stages by as much as 50%, Gibbs says. The evidence for a beneficial effect of exercise is robust except in the late stage of the disease, when it may be too late to intervene.

2. Eat a plant-based diet

A plant-based, Mediterranean-style diet appears to reduce the risk of getting Alzheimer’s. The evidence is most compelling for a variant of the Mediterranean diet called the MIND diet (Mediterranean intervention for neurodegenerative delay) that emphasises adding green vegetables, berries, nuts and other foods rich in flavanols.

3. Mentally stimulating activity

While games and puzzles may be helpful, it’s particularly important to challenge the brain with new learning, as this is thought to help develop new neuronal pathways and synapses. Examples include reading, learning to play a new musical piece, or studying a new language.

4. Social engagement

This can be hard for people living with Alzheimer’s because apathy is often a part of the disease. There’s evidence that those who remain socially active have slower progression.

5. Getting adequate sleep

This is an emerging area of research. There appears to be a cleansing of the brain of toxins, including beta-amyloid (a protein that forms sticky plaques in the brains of people with Alzheimer’s) during sleep by the so-called glymphatic circulation. Also, sleep disorders, including sleep apnoea, are common in patients with Alzheimer’s and should be treated if present.

6. Diabetes and high blood pressure treatment

Both these disorders – diabetes and high blood pressure – can aggravate Alzheimer’s pathology in the brain, as well as lead to vascular dementia, a condition that often coexists with Alzheimer’s. Therefore, detecting these issues early and ensuring they’re well managed is also important.

A Tattoo On My Brain: A Neurologist’s Personal Battle Against Alzheimer’s Disease by Daniel Gibbs with Teresa H Barker is published by Cambridge University Press on May 6, £18.99

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe