AS Sir Alexander Fleming modestly put it, one sometimes finds what one is not looking for.

That is how he described his historic discovery of September 28 1928.

He would later say that, when he woke up on that date, he didn’t expect to revolutionise all medicine by discovering the world’s first antibiotic, or bacteria killer.

We can all be grateful that this amazing Scot did just that.

Born in Darvel, Ayrshire, in August of 1881, Fleming would witness many soldiers die of sepsis during the First World War.

With his glassblowing skills, he came up with an amazing experiment that showed how more of the men had died from antiseptic treatment than by the actual infections.

Clearly, this man was going to make his mark in the medical world, and was able to think outside the box.

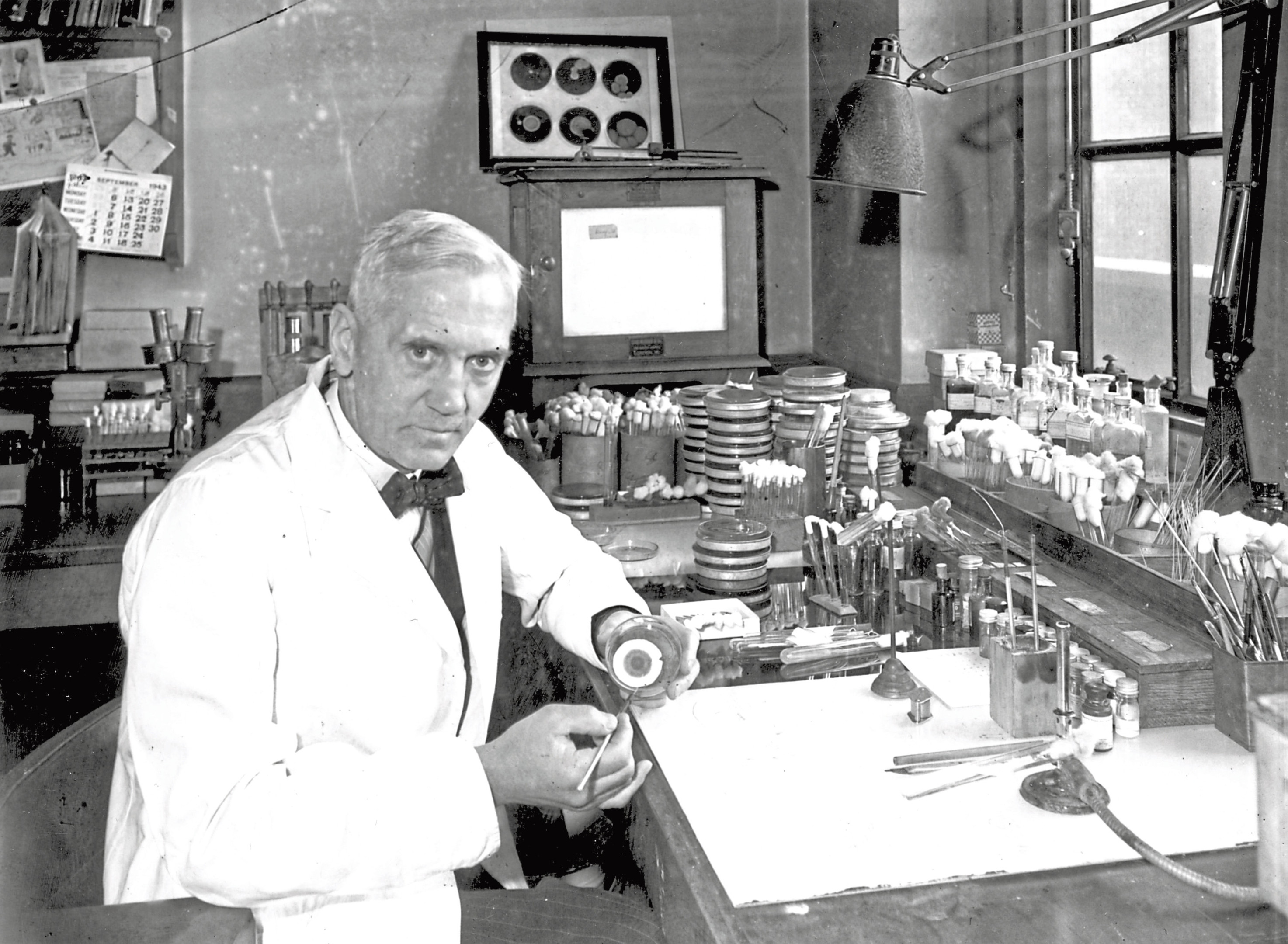

Fleming had a reputation, by 1927, for brilliant work but also for keeping a rather untidy laboratory.

After an August family holiday in 1928, he came back to his lab at the start of September, to find a strange fungus growing in one culture.

Menwhile, the bacteria staphylococci around the fungus had been destroyed.

“That’s funny,” was his first thought, before he showed it to a former assistant, who reminded him that he had made previous discoveries in a similar, almost accidental manner.

Fleming tried growing more of the stuff, finding that it did indeed kill the bacteria that caused disease.

If he was still wondering how big a breakthrough this was, you can move forward to D-Day, 1944, to find out – by then, they had produced enough penicillin to treat all wounded Allied soldiers.

It was nothing less than the birth of modern antibiotics.

Fleming would also discover that bacteria could develop a strong resistance to antibiotics if too little penicillin was used or if it wasn’t used for long enough.

He worried about misuse of the stuff, and made speeches around the globe about this.

Penicillin continues to save millions of people across the world, and a statue of Fleming was even erected outside Madrid’s main bullring, on behalf of matadors grateful that his discovery had seriously reduced the number of deaths in the ring.

He was also, of course, knighted, and has often appeared high in lists of the 20th Century’s most influential people.

Many sources have suggested his discovery was also the most significant medical breakthrough of the century, and there are many people out there who would not be alive without his magnificent work.

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe