On the afternoon of Saturday, June 22, 1985, Detective Chief Superintendent Ian Robinson, the head of Strathclyde Police Special Branch, was at home in Dumbarton painting his garden gate, enjoying a rare day off, when the phone in his hall rang.

The duty officer from the Special Branch control room relayed a message from the Metropolitan Police: two IRA suspects had just boarded a northbound train at Carlisle. It was due into Glasgow at 5.10pm. They were not to be arrested, but followed. Robinson stared at the phone. Jesus Christ, he thought.

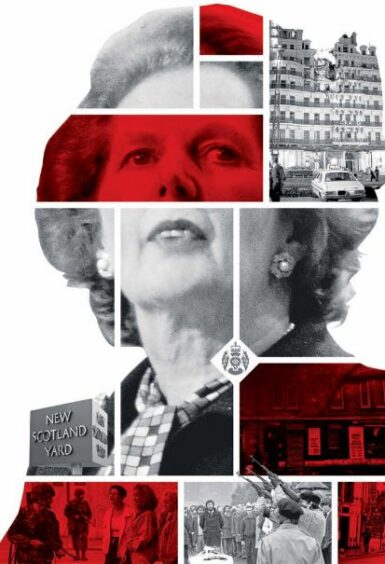

So began the final act in one of the most critical manhunts in British history. It had begun on October 12, 1984, when the Brighton bomb almost wiped out Margaret Thatcher and her Cabinet. For eight months Britain’s security services had hunted the elusive bomber. Then, on this drizzly summer day, they identified him in Carlisle, and he was heading to Glasgow.

The fate of an investigation that had involved the Home Office, MI5, Scotland Yard, the Royal Ulster Constabulary and Ireland’s Garda Síochána would hinge in the next few hours on the decisions of a handful of Scottish detectives. Only now, almost four decades later, can the full story be told.

Strathclyde was the biggest of Scotland’s regionalised police forces and Robinson headed its 80-strong Special Branch, headquartered at Pitt Street in central Glasgow. A tall, soft-spoken former soldier, Robinson had tracked Northern Ireland loyalists who strayed across the Irish Sea but his team had negligible experience of the IRA.

“Call in the surveillance team,” he told the duty officer, before getting in his car and racing down the A82 to Special Branch headquarters. In the control room officers huddled over radios and phones, receiving updates from Met detectives in London. Surveillance colleagues, meanwhile, deployed at Glasgow Central Station.

The previous day the RUC had shadowed an IRA man, Peter Sherry, who sailed from Belfast to Ayr in a coal boat, his purpose unknown. He made his way to Carlisle, where Met undercover officers took over the surveillance. They observed Sherry meeting a small, compact man with dark stubble and a missing fingertip. They identified him as Patrick Magee – a veteran IRA bomber suspected of planting the device that had killed five and injured dozens at The Grand Brighton Hotel during the Tory conference.

Rather than pounce, the Met watchers decided to follow Magee and Sherry. It was a bold decision that risked losing the suspects in return for the chance of discovering what they were up to. Some detectives boarded their train, posing as ordinary passengers, while others hurtled up the M74 to Glasgow.

All Ian Robinson knew was that two Provos were en route – to do what, nobody knew. Britain’s entire security apparatus, in fact, had no idea that for months the IRA had been using Glasgow as a base to blitz England.

Despite being wanted for Brighton, Magee was part of a team – the other members were Gerard McDonnell, Martina Anderson and Ella O’Dwyer – that had rented a room at James Grey Street, a tenement in Shawlands, before moving to an apartment at Langside Road on the other side of Queen’s Park. Quietly, they had assembled bombs and scouted targets south of the border for an ambitious campaign: 16 bombs were to detonate in July and August in London and seaside resorts, wrecking England’s tourism industry.

Magee had already planted the first device at London’s The Rubens hotel, overlooking Buckingham Palace, before rendezvousing in Carlisle with Sherry, the team’s newest member, en route back to Glasgow. Neither man knew that police were tailing Sherry.

In Glasgow the Met team could advise and help with surveillance but Strathclyde would run the show – this was Robinson’s jurisdiction.

When Magee and Sherry disembarked at Central Station about 20 scruffy and casually dressed undercover officers blended with the Saturday evening throngs. Keeping their distance, they murmured running commentary into concealed mics. At one point the targets vanished into the human froth. Desperate pleas ricocheted into ear pieces. Could anyone see them? Hearts hammered as seconds turned to minutes. Then Sherry and Magee reappeared, unaware they had briefly escaped the net. They exited to Union Street, walked to a bus stop and boarded a southbound double-decker, number 57.

Some officers boarded the bus while about five cars followed. After two miles the targets alighted at Govanhill and started to stroll. They meandered a few streets before entering Queen’s Park.

Detective Sergeant Hamish Innes and a female Met officer posed as a couple and took the lead while colleagues hung back. “Eyeballs on target one and target two,” Innes murmured. The IRA men ambled amid joggers and families, then retraced their steps and exited on the north side.

Halfway up a street they doubled back, a counter-surveillance technique known as dry cleaning to check if you are being followed, but did not detect the watchers. They entered the Queen’s Park cafe – the actor Mark McManus was a regular, but not there at the time – and left after a few minutes. They continued for a few blocks and entered a sandstone four-storey tenement in Langside Road.

Officers staked out the building while Robinson, at headquarters, confronted a dilemma. He did not know if the IRA men were armed, had accomplices or were planning an imminent operation. Nor did he know which of the assumed eight apartments inside the building they had entered. Overnight surveillance risked exposure – another IRA member could walk by and spot the watchers, triggering a gun battle in a residential area. But a raid also risked a bloodbath.

With the assent of the Met, Robinson decided to strike while holding the initiative. Instead of a SWAT team with helmets and assault rifles smashing down doors – the orthodox option – he preferred the Special Branch way. “I decided to do it the way we were used to, going in quietly,” he recalled.

The plan was for plainclothes officers to simultaneously knock on every apartment door, identify the hideout and seize the suspects. There were to be at least two officers per flat and at least one armed, with others covering the street, so about two dozen officers. Special Branch did not have enough available officers or guns – many people were off-duty – so Robinson requested firearms officers from other units. He avoided the general police radio, which the press monitored. The last thing he needed was photographers turning up at Langside Road.

The Serious Crime Squad and Regional Crime Squad rustled up about a dozen men. The improvised posse assembled at approximately 7pm at Craigie Street police station, three blocks from Langside Road. Robinson’s briefing was no-frills. Detective Inspector Brian Watson would lead the raid. “They have to be arrested. Don’t take any chances,” said Robinson. There were no diagrams, maps or photographs. Speed was the priority.

At about 7.35pm, the raiding force drove in waning daylight to Langside Road and half-walked, half-jogged the final stretch. At 7.40pm, 23 officers poured into the tenement hallway and split into assigned groups at doorways on each floor. Watson chose a ground-floor door that gave him a view of the stairwell. There was a moment’s hush while he checked everyone was in place. “Go!” he shouted. Knuckles rapped on doors.

Moments later the ground-floor door opened. It was Patrick Magee. He had been expecting the landlord. “Take him!” said Watson. Beefy hands slammed Magee to the ground. “Ground-floor flat!” Watson yelled.

Detectives stampeded down the stairs and stormed the flat. In the hallway they overpowered McDonnell, who had no time to reach for a pistol tucked in his jeans, and barrelled on into the kitchen where Sherry, Anderson and O’Dwyer were at a table. They stared open-mouthed at the invaders. The IRA unit had been sitting down to dinner, oblivious to the police operation. They were too shocked to protest as they were seized.

By luck and guile the Glasgow detectives had captured the Brighton bomber and an entire IRA cell without a shot fired. The news zinged around Scotland Yard and intelligence agencies. An arsenal of weapons discovered nearby sealed the prisoners’ fate at an Old Bailey trial. They were sentenced to life imprisonment. It was one of the biggest blows ever inflicted on the IRA in Britain.

Killing Thatcher: The IRA, The Manhunt And The Long War On The Crown, by Rory Carroll (Mudlark, £25) is published in hardback on April 4. It will be published in the US under the title There Will Be Fire: Margaret Thatcher, The IRA And Two Minutes That Changed History (Putnam, $29)

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe

© ANL/Shutterstock

© ANL/Shutterstock