PEOPLE normally take a long time to get over a crisis, but 60 years ago NASA hit back with the perfect response.

In the summer of 1958, paranoia about the Soviets’ early forays into space completely obsessed America’s leaders and ordinary people.

Russia had launched the first-ever artificial satellite in October the previous year, and it sent such alarm through the West that it became known as the Sputnik Crisis.

The director of NACA, the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics, warned that “it is of great urgency and importance to our country in prestige and military necessity that this challenge be met”.

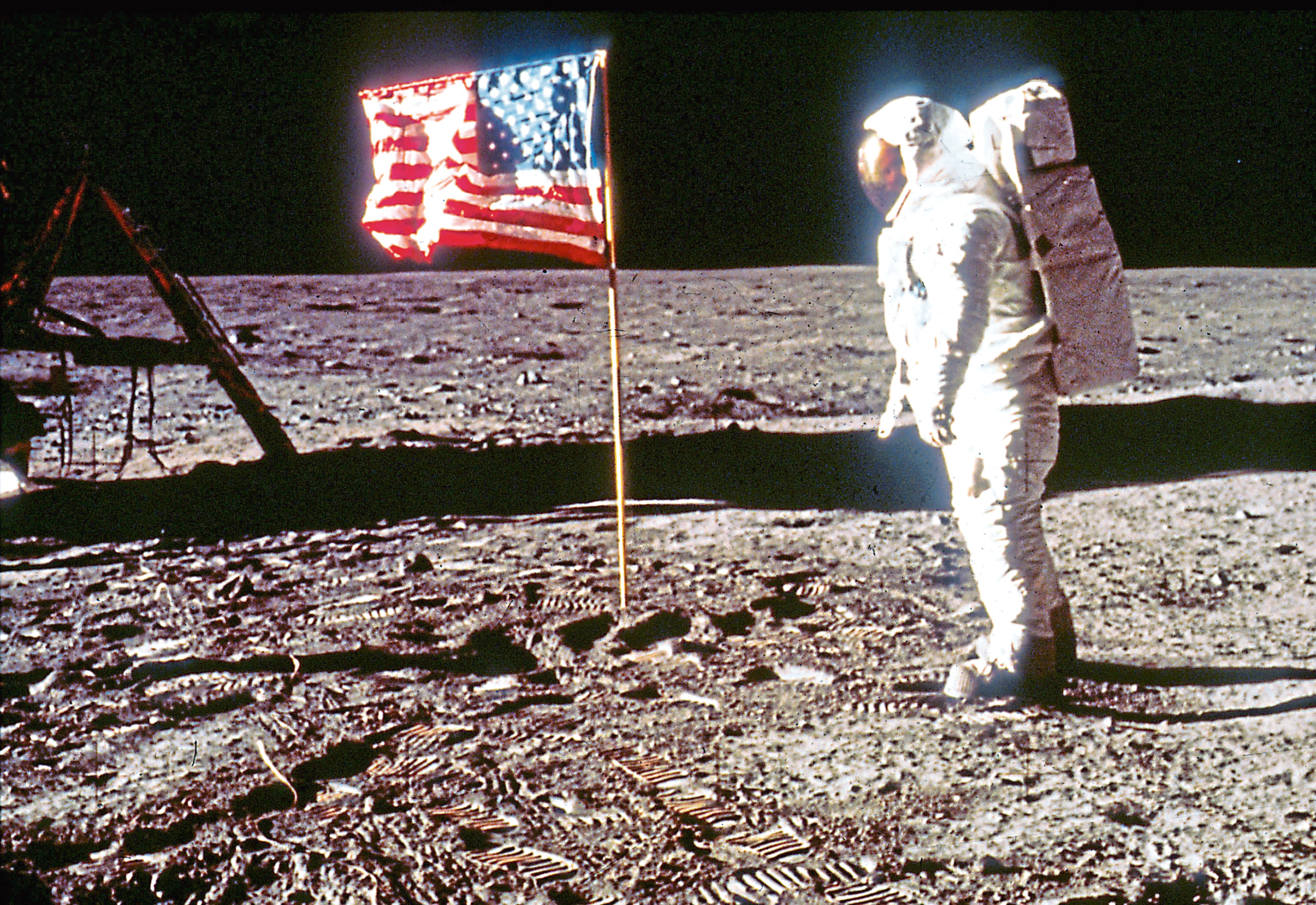

Boy, was it met – by 1969, just 11 years after they founded the National Aeronautics and Space Administration, NASA, America put men on the moon.

If the Soviets had nosed ahead early on, the United States had come roaring back, and in this special year for NASA it is still the world leader in matters space.

Established by President Dwight D Eisenhower, NASA was to be a civilian, not military, organisation, despite the fact it was also to be a Cold War competitor with astronauts pitched against cosmonauts.

The Apollo moon landing missions, Skylab, the Space Shuttle and even the International Space Station have all been led by NASA.

Specialised vehicles to operate on surfaces no human had seen before, and unmanned launches, boots, gloves and all manner of gear that has never been required on Earth, have all been created by NASA.

Behind it all, of course, are the brilliant scientists who work for them, exploring the solar system and working out how we can take advantage of what is out there.

If anyone is going to come up with the things we will need to survive when we have used up all of our own planet’s resources, it’s NASA.

And even keeping an eye on how Earth is doing, with the Greenhouse Gases Observing Satellite, is mainly down to NASA.

The agency’s boss is nominated by the US President, with approval from the US Senate.

As the man in charge of the money, the top guy at the White House also has last say on new NASA projects and decisions on when to abandon others.

Today’s younger people, who weren’t alive when humans walked on the moon, are in awe of the global power of the folk who run Facebook, Twitter and other major organisations.

But the chaps and ladies at NASA have literally taken us much, much further – NASA has sent up there the very satellites that we use for mass communication, not to mention probes that have explored Venus and Mars along with tours of the outer planets.

During the space race with Moscow, they landed a dozen men on the moon between 1969 and 1972, created a space shuttle that could be used again and developed a space station alongside the post-Soviet Russians.

Even an unmanned probe to Jupiter has been achieved, and the possibilities are endless if people keep investing and countries remain willing to work together.

None of that, though, is likely to happen if NASA aren’t around to contribute their wealth of knowledge. The Apollo Programme, of course, is the pinnacle so far, and the most-discussed, most awe-inspiring part of NASA’s relatively short history.

It was President John F Kennedy who had asked Congress, in May of 1961, to fund the amazingly ambitious idea of getting a man, an American man, to stand on the moon.

JFK wanted it done by the end of the 1960s, and would get his wish. They estimate that in today’s money it would cost more than $213 billion, and it involved rockets and spacecraft of a size nobody had seen before.

It also had two vital parts, the one that got them up there and the smaller one that would hopefully get the three astronauts back to our planet.

NASA is the only organisation that has sent manned missions beyond low Earth orbit, or landed humans on another celestial body.

Of the dozen men to walk on the moon, Buzz Aldrin is now 88, Neil Armstrong deceased, and the other 10 are all either well into their 80s or have passed away.

All American, all NASA astronauts, and all having done something that countless people of every age and nationality would give our right arms to do.

There has been a vast wealth of new knowledge, of our past and possible future, of mechanics, heat flow, magnetic fields, solar winds, meteors and, of course, of how humans cope when stuck together in places nobody else has ever been.

With the moon conquered, one planet beguiles NASA as much as the rest of us, from sci-fi writers to film-makers, from songwriters to those who suspect it may have the very things we are running out of – Mars.

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe