It was 1940, and deep in the medieval fortress of Tittmoning, an internment camp near Munich, Julius Green was in his medical quarters and his life was about to change forever.

Green, a dentist from Glasgow, had recently been captured at Saint Valery, and his medical and dental skills were being put to much-needed use inside the camp. When a captured colonel who was in touch with MI9 using the new code developed by British Intelligence via Prisoners of War letter learned of Green, he immediately saw the potential in his role.

A dentist who could travel between camps, and who would be in close contact with the Germans while seeing to their dentistry, could be a great asset if he knew the art of secret communications. So, for the next three hours, the outgoing and gregarious Green learned the method of writing coded messages.

Captain Green would eventually end up in Colditz, where he worked with fellow secret agent, Quartermaster Sergeant John Brown, to bring down a double-agent who was planted inside the castle by the Gestapo. Walter Purdy gave away intricately plotted escape plans to the Germans, and it was thanks to Green and Brown that he was eventually exposed and sent to prison.

That Green was able to operate literally under the nose of the Nazis for so many years of the war and not be discovered as a secret agent was testimony to his bravery. That he did so while also covering up the fact he was a Jew was remarkable.

It is a story that enthralled author Robert Verkaik who, while digging through the National Archives, discovered the story of Purdy, Green and Brown, and felt it was time a fresh light was cast on their remarkable tales.

Green’s son, Alan, is pleased to see his dad’s astonishing war-time efforts being remembered again. “People who put their lives on the line like that should be remembered,” said Alan, 75. “He was a strong-willed character and a clever guy but more than anything else he was a man of honour and ethic, and all his views were based on those things.

“The information he brought back was amazing. He lived the war a bit when he came back. Obviously it was a big event in his life. He would talk about how he was lucky compared to some. He saw the cattle trucks full of people.”

Green was born in Carlisle and moved to Killarney, and then to Dunfermline. “There were six Jewish families there and they all went down the mines,” said Alan. “It’s a background people don’t equate to the average Jewish person. Most of the families moved to Glasgow eventually.”

Green followed in his father’s footsteps by taking up a career in dentistry, studying at the Dental School of the Royal College of Surgeons in Edinburgh before joining a practice in Parkhead, Glasgow. He enlisted with the Edinburgh University Officer Training Corps, part of the Army Reserve, and was sent to France in 1940 with the British Expeditionary Force, before being captured.

“He was decorated for going out under heavy fire and collecting the wounded,” said Alan.

“I remember going on a trip to Ballachulish with him when I was 15 or 16. He got talking war stories at the bar with another fellow, who said he commanded the motor torpedo boat squadron on the Channel, and one of their duties had been to try to pick up the 51st Highland Division at Saint-Valery-en-Caux, six weeks after Dunkirk. ‘Yes’, my father said, ‘I was waving to you!’”

Alan described his father as an extrovert. “When he was first captured, the Germans said if they could tell them anything new they would help the prisoners out a bit. No one did, of course, but my old man put his hand up and said that there had been trouble with the messages being carried by pigeons falling into the wrong hands, so the RAF had solved it by crossing pigeons with parrots. They didn’t see the funny side, though, and locked him up for a week,” he said.

He would challenge German guards to boxing matches but he was also able to keep them on-side to glean information. One grateful officer whose teeth Green had tended to presented him with a dachshund, Sandy, who became a close companion through hard months. But when Green failed to salute an arrogant second-in-command Nazi, and Green told him it was because he didn’t behave like a gentleman, the officer shot Sandy dead.

Verkaik said: “Green had already witnessed their cruelty; he’d seen the Poles and Jews being beaten and executed in working parties, and his dog being shot dead only confirmed everything he thought about them. The things he saw, he was powerless to intervene.

“He was an extraordinary chap, and didn’t fit any stereotype or sense of what a dentist was or even an officer. He must have known he was a medical inspection away from being executed.”

In fact, Green was put through an inspection, after telling traitor Purdy he was a Jew. Green, who had already met and had suspicions about Purdy in another camp years earlier, was reunited with him in Colditz. Believing that Purdy would be immediately hanged after he was exposed, Green didn’t count on the squeamish British officers in the camp being unable to go through with the execution, allowing Purdy to go to the Germans and expose Green.

But the excuse of an embarrassing health issue told by Green and British medical officer Captain Dickie saw the dentist live to see another day.

Having discovered enough information from him, Purdy was interrogated by their superiors and soon admitted to having spent time at a German propaganda camp, from where he had broadcast in English on behalf of the Germans, a minor Lord Haw-Haw.

Green was liberated from Colditz in April 1945 and he later testified, along with Brown, at the treason trial of Purdy, who would serve just nine years for his crimes. As Purdy was being led away at the conclusion of the trial, he shouted: “I’ll get you, Green.”

By the time Purdy was released, Green was married with two children and, after a time selling electrical goods, had returned to dentistry. Shortly after the release, a call was taken at his office from a man who said he was coming to see Green.

“His unfortunate words were, ‘I’ll get him at his house’,” explained Alan. “My father phoned the police and armed officers arrived. But it turned out it was someone he’d served with who had docked on the Clyde and wanted to look dad up. We were all invited on board, and I remember this enormous cabin full of curries had been laid on, which was quite unusual for Glasgow at that time.”

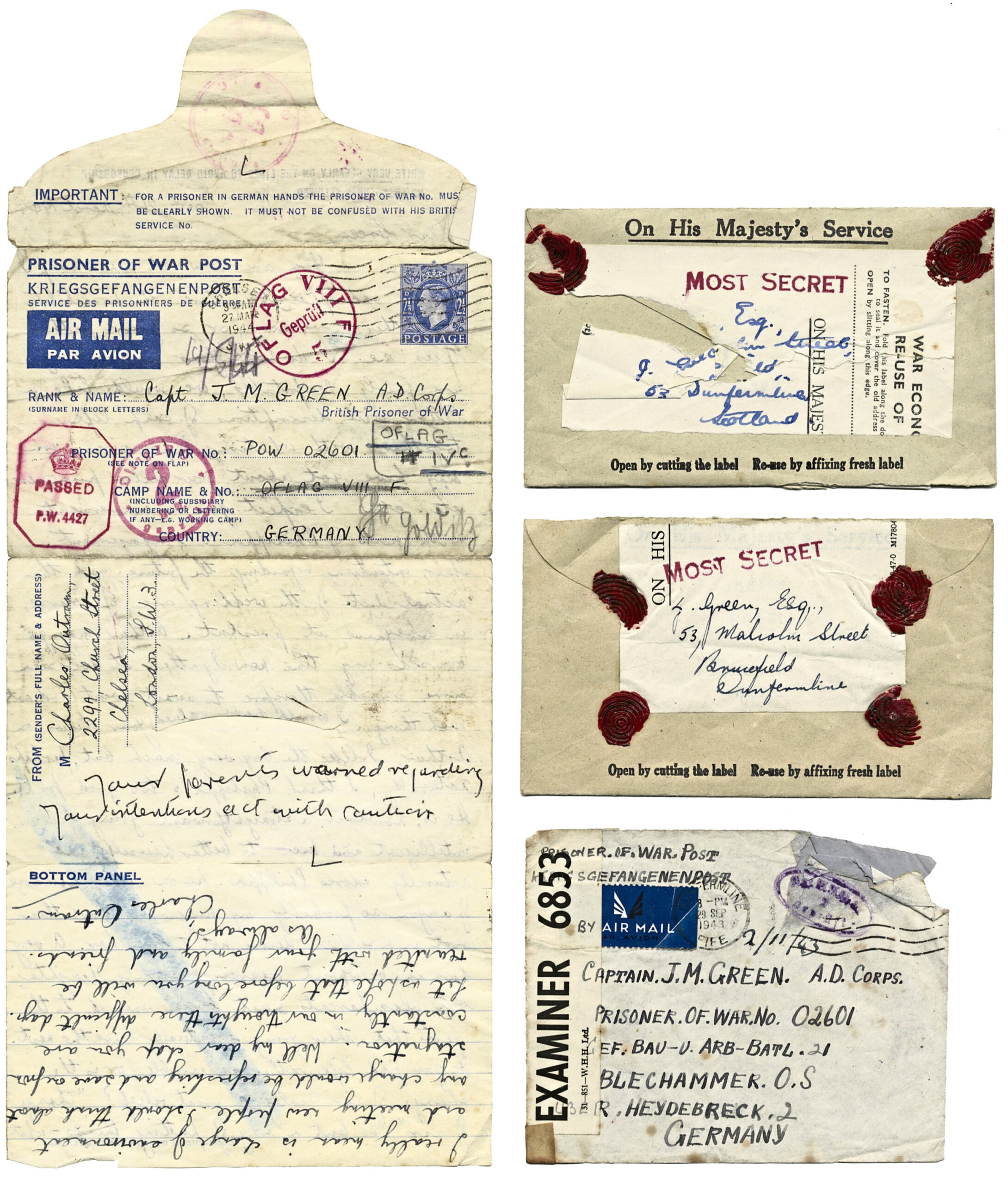

Alan recalled seeing the coded letters, maps and photographs as he grew up. “MI9 sent all the letters to my grandfather, even the coded ones, which were just nonsense stories. They ordered him to destroy them after reading them but he never did.

“He had an aunt in Boston who sent him a letter wishing him well over Yom Kippur – if the Germans had seen that they would have done him. An emergency letter went from MI6 to the family saying please don’t let your relative send any more letters.”

Verkaik continued: “He wasn’t really communicating with his family in the way other PoWs were, which is something I think is forgotten. They were only allowed to write a certain amount per month, so he was giving that up to write in code and so wasn’t having genuine contact with his family. It was quite the thing to sacrifice letters to loved ones. He was creative, brave and resilient.”

In the early 1970s, Green decided to write a book about his time in the war, From Colditz In Code. “It’s fair to say Green was the first to disclose the code-writing system when he wrote the book,” said Verkaik. “Before that, there had been an informal secrecy over them.”

Alan recalled: “He had to receive a pass for the book, and he wasn’t well at the time, so I took the train to London, where I was escorted into White Hall. I was taken into a room with Vice-Admiral Lord Denning, who shook my hand and gave me the paper to take back to my father, which allowed him to publish his book.”

Alan said: “Having a photographic memory, he was the ideal man to pass on the code. This was ongoing for a number of years and he didn’t know when someone would give him away. That stands high in terms of bravery, I think.”

The Traitor Of Colditz by Robert Verkaik is released by Wellbeck on Thursday

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe © Bournemouth News/Shutterstock

© Bournemouth News/Shutterstock © SYSTEM

© SYSTEM