Noirvember is in full swing in Scotland. The 11th month of the year is devoted to the darkest corners of cinema, where the devious and the downtrodden reside.

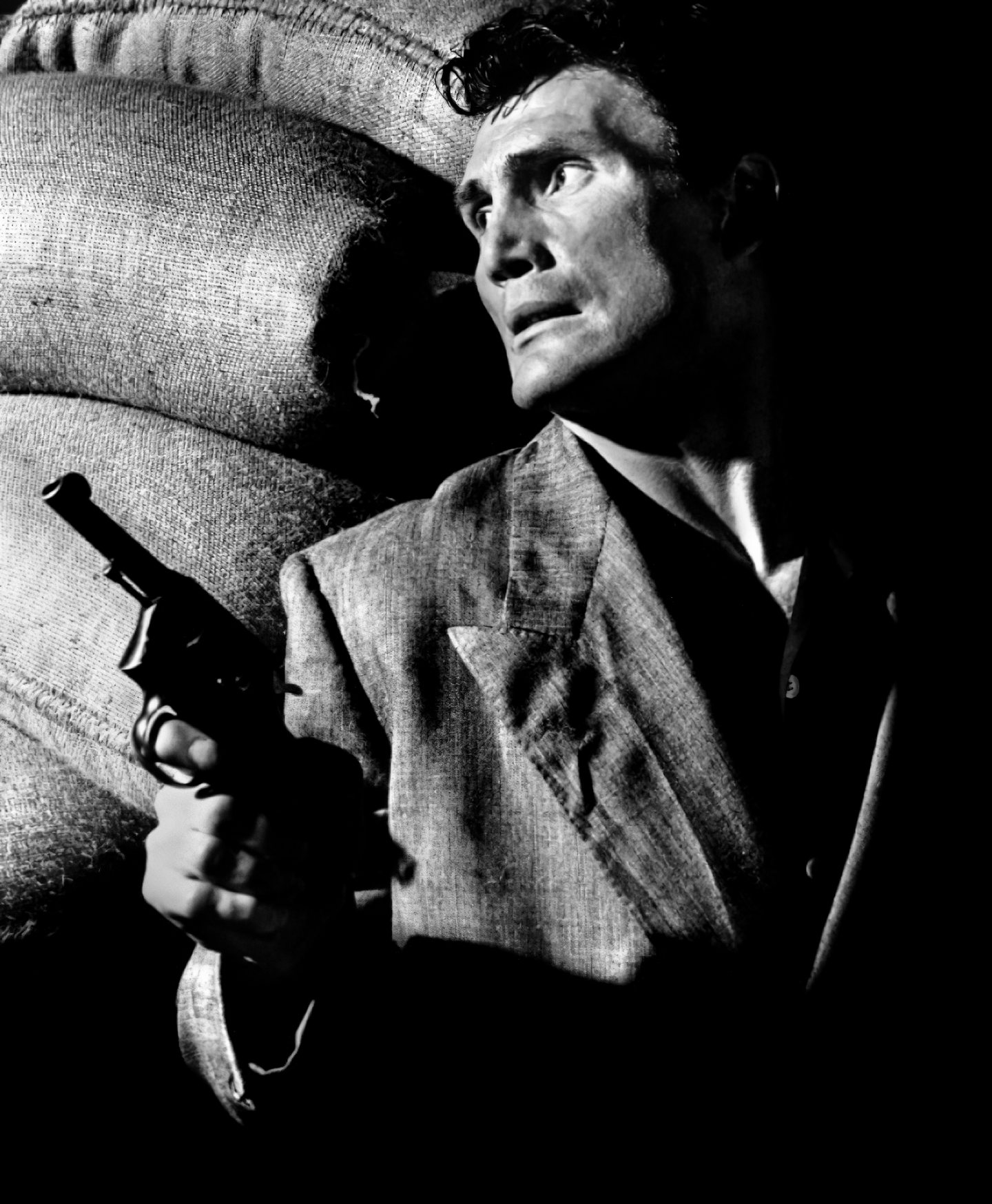

A new celebratory compendium of stunning still photography from the 1940s heyday of film noir might be bringing fresh attention but, in truth, the hard-boiled genre of fast-talking, double-crossing, femme-fataling has never been away.

When noir royalty Humphrey Bogart or Robert Mitchum gazed out of the shadows at the rain-soaked streets, these films had a weary, savvy style that set them apart from the rest.

No one was as insolent or isolated as the ‘50s Bogart, no one so languidly dangerous as Mitchum. Nobody was as heartlessly sexy as Barbara Stanwyck, as creepy or craven as Peter Lorre, or as cynically amused as Lauren Bacall.

The men wore hats. The women wore slinky clothes. Everyone smoked and drank like crazy. Everything was shot in dark shadows and sweaty close-ups, with titles like D.O.A., Gun Crazy, Kiss of Death and The Devil Thumbs a Ride. Yet for all its popularity, film noir is one of those terms people bandy about without really knowing what it means. Critics like me bandy it about, too.

This was a world created seemingly without pity. A world of rats, killers, grifters, thieves, and squealers. There were a few cops – most were crooked, and rarely around when you needed them. And some reporters, many of whom had the facts wrong.

There were scheming dames, often bigger double-crossers than the guys. At the top, were the rich society folk with their guilty secrets, private time bombs just about to blow their lives apart.

The rules of what makes a film noir are vague. Some purists insist that only black-and-white films qualify, since the term is based on a time when colour was rare. Others say no period piece – a Western or war film, for example – can be film noir. Oddly, no director ever set out to make a film noir, because none had heard the term.

At the end of the Second World War, French cinemas were flooded with the American films they had missed during the war until the defeat of Germany.

Having emerged from a great national nightmare, French movie enthusiasts loved this new vision of their American liberators with downbeat themes, moody images, shady characters, and sexy women with eyelids at half-mast. They called the movies “film noir” – black film, with a dark heart.

But to the stars and crews working in the Hollywood movies factories, many of these films were simply B movies: often churned out on cheap budgets, with low lighting to mask the flimsy sets. “You call it film noir. We called it a 15-day shoot,” wisecracked Richard Widmark, one of the great early stars of the genre.

Moviegoers adored these films because they were riskier than most studio movies. They had sexy, violent storylines that would never get past the censorship that was placed on bigger-budget pictures, and had images that were considered too hardcore to be associated with major stars of the time.

Off screen, some of the stars of noir also had led lives that dealt in shades of grey; in 1944, the director Howard Hawkes talent-spotted a shy 19-year-old model called Betty Perske, and resolved to turn her into a star – and his mistress.

He taught her how to speak, how to dress and even changed her name. But the dame had plans of her own; when the newly-minted Lauren Bacall met her hard-drinking, much-older co-star on the set of their first film, To Have And To Have Not, she fell immediately for Humphrey Bogart and married him within months, leaving Hawkes to face the wrath of his long-suffering wife.

Noir was often unpredictable because B movies didn’t require happy endings. Instead they celebrated hard-headed men and hard-hearted women, exchanging hard-boiled dialogue you could use to time your eggs.

Each year, about half a dozen new films carry the torch.

Recent release Amsterdam had many film noir qualities in its story of two First World War buddies (Christian Bale and John David Washington) accused of murder who need gorgeous Margot Robbie to clear their names, while Nightmare Alley, with Bradley Cooper as a handsome circus hustler, is an update of a classic noir first adapted for the big screen in 1947.

What the older movies demonstrate is the durability of the original mean and moody movies. As Joan Bennett says in 1948’s Hollow Triumph, “it’s a bitter little world,” and with all the tumult and uncertainty today, no wonder these tense, ominous films still resonate with audiences.

From the book

Film Noir Portraits by Paul Duncan and Tony Nourmand collects some of the most innovative and striking publicity photographs taken during the 1940s heyday of the genre.

Here, in an extract from the introduction, film historian Duncan explains why movie studios commissioned such stunning still images.

Each major studio employed a number of still photographers situated in their own department where they could develop the film and “work” on the negatives (removing spots, freckles and wrinkles) to make the best prints so that the stars were as glamorous as possible.

It was common for several photographers to work on the same movie, as schedules dictated.

Over the course of a production, a few hundred or a few thousand images would be captured –depending upon the budget – and an approved selection would be used for promotional purposes in newspapers and magazines, as well as the basis for posters and lobby cards.

If the production was lucky (or had a good PR department), a big magazine or newspaper, like Life, Look, The Saturday Evening Post, or The New York Times, would send a photographer to do a feature.

These photographers – like Gjon Mili, John Florea, Walter Sanders, Peter Stackpole, and Jack Birns – were photojournalists, able to quickly connect with their subjects and capture the necessary images. Their candid set photos or special shoots with the stars would become fixed in the public imagination in such a way that readers would be intrigued or enticed to go watch the movie.

However, the movie also needed to be marketed in the traditional manner, so the actors got into costume, make-up and character, and visited the still department

for portraits.The still men were masters of light, and these photo shoots under controlled conditions allowed them to exercise their craft to the utmost degree.

The requirement was that each of the stars had single portraits taken, usually against a blank background – the female stars would have singles with multiple costumes – with the actor sometimes looking directly into the camera.

Nobody looks at the camera on a movie set, so these portraits gave the viewer a direct connection to the stars.

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe © Everett Collection Inc / Alamy S

© Everett Collection Inc / Alamy S © SYSTEM

© SYSTEM © ScreenProd / Photononstop / Alam

© ScreenProd / Photononstop / Alam © SYSTEM

© SYSTEM