It has become the essential feminist novel, a modern literary classic.

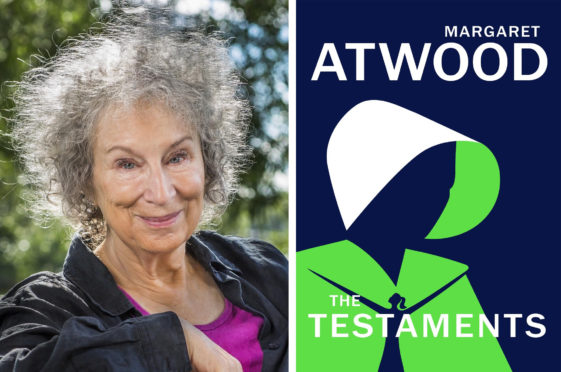

And, now more than 30 years after publication of Margaret Atwood’s landmark The Handmaid’s Tale, there is a sequel.

In 1985, the Canadian author could not have guessed a TV series decades later would propel her story into the stratosphere.

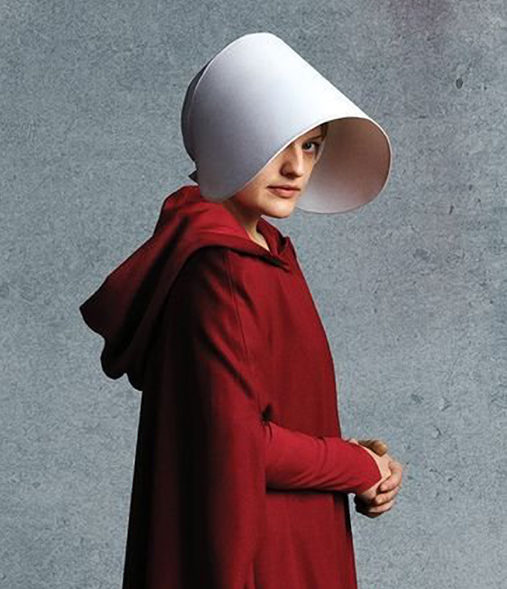

Viewers all over the world have for the last two years been gripped by three seasons of The Handmaid’s Tale set in Gilead, the fictitious totalitarian dystopia that treats women as property and forces the fertile among them into child-bearing slavery.

And the multi-Emmy-winning US drama – aired on Channel 4, starring Elisabeth Moss and now in the third series – has created an audience hungry for more. Now Atwood has delivered. More than three decades after The Handmaid’s Tale comes The Testaments, arguably the most anticipated sequel of the decade.

Among those eager to read the book, which will also be adapted for TV, is author Rebecca Stott. Her deeply personal family memoir of growing up in, and breaking away from a patriarchal fundamentalist Christian cult – In The Days of Rain – took the 2017 Costa Biography Award.

A professor of literature, she said: “The Handmaid’s Tale is one of the most prophetic and important books of our times. I can’t wait to read the sequel.”

But wait she, like the rest of us, must. Its contents are being kept under lock and key.

Even the Booker Prize judges – by whom it has been longlisted – have been sworn to secrecy, bound by what they described as: “a ferocious non-disclosure agreement”. All they would say is that it is at once “terrifying and exhilarating”.

All will be revealed just before midnight tomorrow when Atwood will read from the sequel at a special overnight opening at Waterstones in London’s Piccadilly.

The next day the multi-award winning author will be in conversation with the BBC’s Samira Ahmed at the capital’s National Theatre – an event which will be screened globally to more than 1,500 cinemas including picture houses across Scotland.

She promised in a statement ahead of the event: “Everything you’ve ever asked me about Gilead and its inner workings is the inspiration for this book. Well, almost everything! The other inspiration is the world we’ve been living in.”

University of East Anglia-based Professor Stott, who is also a novelist and historian, and who traces her Brethren family back to 1900s in Cockenzie and Eyemouth, said: “What Atwood wants us to do is to see The Handmaid’s Tale as a mirror.”

Despite its vintage, the book – and the TV series – feels contemporary when read against a backdrop of current day USA where women are challenging the erosion of their rights. This year alone nine states have passed abortion restrictions that could challenge an established constitutional right.

Professor Stott said: “I think it is obvious to any of us who are watching The Handmaid’s Tale, not just people raised in cultures like I have been, that the control of women’s reproductive rights, the silencing of women, gagging orders, all of these things are in the book.”

For Prof Stott, the world of Gilead is even closer to reality. Reliving the childhood in which her father was an influential preacher with the Exclusive Brethren – now known as the Plymouth Brethren Christian Church, she said: “I am a fourth-generation member of the Scottish Exclusive Brethren. It was a closed community. The Brethren are absolutely not interested in recruiting anybody from outside. You are born into it.”

And she claimed: “Women were subject to their husbands, to their brothers, to their fathers. Brethren girls and women wore headscarves to demonstrate their subjection to God; they were also not supposed to cut their hair and had to wear it down their backs.

“They were not allowed to wear trousers or make-up. Dress lengths were always below the knee. There would be disapproval if you showed any awareness of fashion or style.

“Women were expected not to work once married and to have large numbers of children. There were no female leaders in the Brethren church; that would have been an anathema. Women were not allowed to contradict the opinions of men. They would take lines from the Bible – much as The Handmaid’s Tale does – to justify women’s silence.

“We had no choice.”

Like Atwood’s heroine, June, Stott says she, “often seethed with rage and frustration,” and asked herself, “Would I have to get married and be silently obedient like the Brethren women? Why wasn’t anyone asking any questions?”

Prof Stott added: “What happens in Atwood’s first book is that people don’t see it coming. There are little warning signs as the law is changed, as women’s rights are gradually eroded, and men get more power while women are brought back under patriarchal control. They are too busy to notice where it is going until suddenly, the full regime is there and no one can get out. That’s the really chilling thing.

“What Atwood warns us about is not looking away and doing something and not just watching in horror.”

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe