Trawl through the TV archives and you’ll be surprised how many classic sitcoms were penned by writing partnerships, and over the coming weeks we’ll spotlight some of British TV’s most successful double acts.

Our series kicks off with John Esmonde and Bob Larbey, whose output included The Good Life, Ever Decreasing Circles, Get Some In! and Please, Sir!.

The writers became friends on a school trip in Switzerland. Esmonde once told me that they were both “loonies with lots in common, including a crass schoolboy humour”.

Their friendship continued into adulthood and they’d frequently meet for lunch, idling away the time bemoaning their jobs and wishing they could do something else with their lives.

Eventually, they did just that, deciding to try their luck as professional writers over egg and chips at a Wimpy restaurant in London.

It wasn’t long before they sold their first piece of comedy writing, marking the birth of glittering careers comprising over 16 hit TV shows.

Initially, they wrote revue sketches before turning their attention to radio and, ultimately, TV, where they started off supplying material for The Dick Emery Show.

From day one, Esmonde and Larbey found working together easy. “We made each other laugh and a shared sense of humour is often the basis of a good friendship,” explained Larbey.

“We didn’t have to explain things to each other, it was as if we had a telepathic sense,” added Esmonde.

As professionals, it was important they created an environment conducive to writing saleable material. But until they could afford to rent their own office, a boxroom in John Esmonde’s home had to suffice.

“We never started work early because we’re totally useless first thing in the morning,” Larbey told me, laughing. “We’d start about 11 and work until six, maybe longer if we were on a roll. That suited our body clocks.”

Working from home had its downside, though. “The only setback was when a cricket match was on TV because we’d nip down to watch a few overs.”

Unlike other successful writing partnerships, tasks weren’t allocated on individual strengths – responsibilities were split equally.

“We used to write longhand rather than type the script or put it on to computer straight away – we always found that distracting,” admitted Esmonde. “We’d take it in turns doing the writing while we played all the characters out very badly, but in our ears they were perfect.”

Their first stab at sitcom – focusing on the lives of maintenance men at a manufacturing company – came in the shape of 1966’s Room At The Bottom starring Kenneth Connor and Deryck Guyler.

With an entire TV series now under their belt, it was time for Esmonde and Larbey to move out of John’s boxroom and find an office.

“Once we started in television we became more serious and financially secure,” said Larbey, whose move to the Sussex coast was another factor in the need for a new office.

They found a tiny room in Dorking. The location, overlooking a car park, was far from palatial but just the ticket for two writers wanting to free themselves of potential distractions.

“We didn’t want glamorous offices with fantastic views,” explained Esmonde. “If we were sitting around in swanky furniture admiring the views, it wouldn’t be conducive to work. If your surroundings are basic, you get on with things.”

“We quickly turned the place into a slum, as writers usually do,” added Larbey. “It wasn’t long before there was fag ash, cups that hadn’t been washed for days and bits of paper everywhere.”

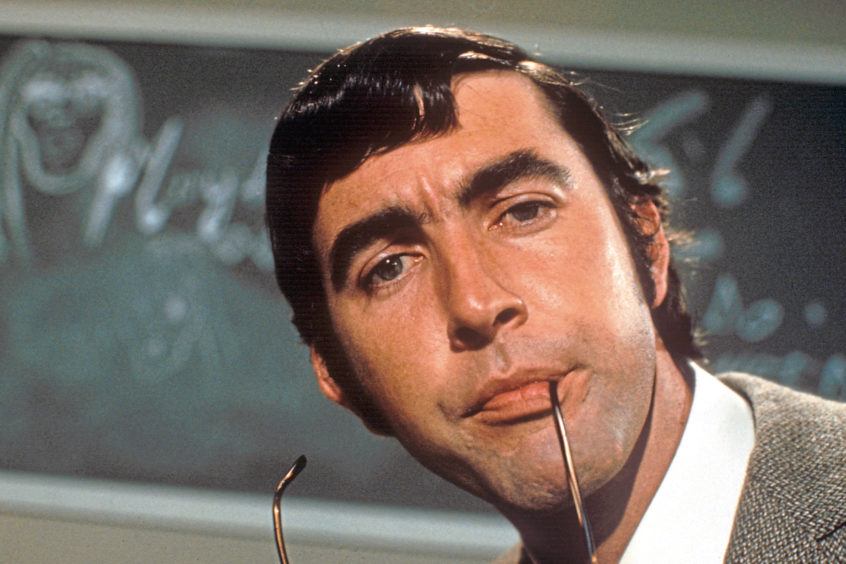

Esmonde and Larbey’s first big hit was 1968’s Please, Sir!. The antics of Fenn Street Secondary Modern’s Class 5C and their callow teacher Bernard Hedges (played by John Alderton) made good viewing.

LWT’s sitcom quickly became a success and 57 episodes were screened over a four-year period.

Reflecting on the sitcom, Larbey couldn’t recall what made them base the series in a school, although admitted it was a natural subject to explore.

“Being a bit young at heart, or childish, we still had a fair recall of school, the ambience and all the sounds in the corridors. The tension occurs when you stick a young idealist teacher in a position of having to teach kids who are much more worldly-wise than himself.”

The show’s instant success engendered confidence in the writers’ abilities as professional scribes. “We were asked to do more and more and started thinking: ‘We’ve actually made it. We really don’t have to go back to work!’”

The series’ success led to a sequel, The Fenn Street Gang, exploring the kids’ lives post-Fenn Street Secondary. Although it never hit the heights of Please, Sir!, 49 episodes were made.

The 1970s was a busy decade for Esmonde and Larbey and by 1975 they had two shows running in tandem.

While The Good Life was entertaining viewers on BBC1, ITV was screening the first of 34 episodes of the national service sitcom, Get Some In!.

When the writers were looking around for a new idea for the independent stations, they called upon their personal experience again. “We asked ourselves whether there was anything else we knew about and suddenly thought of national service. We’d both done two years so it seemed an obvious choice,” said Larbey.

Arguably the writers’ biggest successes involved working with Richard Briers. While The Good Life marked the apogee of their writing partnership, Ever Decreasing Circles was my personal favourite – a view shared by millions of others, too.

The first of 27 episodes was screened in 1984 with Briers playing the insufferable organiser, Martin Bryce, whose obsession with minutiae drove his friends and wife, played by Penelope Wilton, insane.

This was sitcom writing at its best and, as far as Larbey was concerned, the show’s popularity was partly down to “having a little bit of Martin in all of us”.

The writers relished the chance of working with Briers. Talking to me before Briers’ death, Larbey said: “Richard is such a good actor and a nice bloke. John and I were able to write speeches that flowed very easily from his mouth.

“We’ve always had an affinity with him. He always said our lines perfectly, just the way we’d written them. The inflection, everything, would be perfect.”

Although the writers struggled to pinpoint the actual moment they conceived the idea for Ever Decreasing Circles, the Martin Bryce character was influenced partly by an amateur footballer they knew.

“Bob and I played old boys’ football and had to attend regular meetings. This chap would arrive with a briefcase and give a dissertation on how to take penalties. Now, think of this happening in someone’s living room. He was unbelievably English in his fairness but so frustrating.

“He was always very keen. I remember one week, we were playing a match but didn’t have a referee so he decided to ref and play as well!”

Martin was terribly tortured and always heading full-steam towards a nervous breakdown, thanks to the self-inflicted obsessions which dragged him down like quicksand.

Although Esmonde and Larbey were among the UK’s most successful TV writers, not everything they touched turned to gold.

In 1977, they were, once again, working with Richard Briers. This time, the London-born actor played habitual liar Ralph Tanner alongside Michael Gambon as Brian Bryant.

Two series of The Other One were made but the sitcom left viewers and critics unimpressed, despite the writers ranking it among their favourite pieces of work.

Esmonde and Larbey felt that the lack of success was partly due to the public’s inability to accept Briers – with his proven track record playing benevolent individuals – as an unscrupulous character.

This disappointed John Esmonde. “We thought he was brilliant but the audiences didn’t like seeing their Richard as a rotter.”

Esmonde, who died in 2008, aged 71, and Larbey, in 2014, aged 79, were experienced enough to take it on the chin when one of their efforts bombed.

As well as The Other One, Just Liz – starring Sandra Payne and Rodney Bewes – a football sitcom, Feet First, and Down To Earth finished after just one series.

“It’s difficult putting your finger on why something doesn’t work, usually it’s a mix of reasons,” admitted Larbey.

The writers continued working throughout the 1980s and early ’90s, most notably penning five series of Brush Strokes, starring Karl Howman as painter and decorator, Jacko.

The last sitcom penned together was the ill-fated Down To Earth, after which they called it day. But their decision to dissolve the partnership was not based on the sitcom’s lack of success – they were too battle-hardened for that.

“We decided before the show was even commissioned that it would be our last,” said Larbey.

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe © Allstar/YORKSHIRE TELEVISION/BBC

© Allstar/YORKSHIRE TELEVISION/BBC © ITV/Shutterstock

© ITV/Shutterstock © Allstar/BBC

© Allstar/BBC