If one movie executive had his way, Michael Corleone would have been played by Jack Nicholson instead of Al “too short” Pacino but fortunately director Francis Ford Coppola had no interest in turning Mario Puzo’s novel into One Disrespected The Cuckoo’s Nest.

He also won the tussle over Vito Corleone and cast his first choice, a then out-of-favour Marlon Brando, instead of Orson Welles. Still, no one complained about the casting of the horse’s head: it was a real one, obtained from a neighbourhood dog food supplier.

Usually, great movies take decades to receive their due but from its opening day, March 15, 1972, The Godfather was recognised as a landmark work of storytelling and art that became, for a time, the highest-grossing movie ever. Many call it the best movie of all time, despite a troubled production and constant battles with the studio.

The Godfather probably has as many famous lines as Hamlet, with a significant portion of the population talking about spending time with your family being the mark of a real man, that’s when they’re not insisting it is time to go to the mattresses, or sleep with the fishes.

Its famous fans include President Barack Obama, who nominated it and The Godfather: Part II as his favourite classic movies, adding: “Three – not so much.” Of course nobody prefers The Godfather Part III, the 1990 sequel. Director Coppola made the disastrous decision to cast his own novice daughter as Mary Corleone. Sofia Coppola went on to become a successful movie-maker in her own right but aged 18 she gave a performance so flat that you could stay warm for two hours by striking a match to her wooden acting.

Her father was also affected by the Curse of the Godfather. He hadn’t even wanted to make The Godfather, but when he thought he was out, they pulled him in, with the offer of a fee that would clear his £1 million debts. Yet while the trilogy’s first two films are Coppola’s best work, they also paved the way to his downfall as a director. The film-maker began to believe that every story needed to be supersized into gigantic operatic movies.

Apocalypse Now, Bram Stoker’s Dracula, One From The Heart and The Cotton Club all confirm that this ain’t necessarily so. At best, these were interesting failures, and in the case of his strident musical One From the Heart, it was like spending two hours next door to a burglar alarm.

As the hoopla begins around next March’s 50th anniversary of its release, the original ageing Don still deserves respect, even though younger movie fans and students may struggle with the film’s ponderous pace and the stately three hours it takes to track Michael Corleone’s slide from decent, diffident young soldier to cold-blooded killer.

At least the unhurried storytelling gives new viewers bags of time to puzzle over some of the film’s stranger scenes, such as how the mafia got a horse’s head into somebody’s bed without waking them up? And wow – is that subtle, soulful young Corleone really Al Pacino? It’s hard to remember a time when we could look forward to a Pacino performance with gleeful anticipation rather than concern for our hearing.

The Godfather is proof that once upon a time, the New Yorker was an actor of quiet intensity, rather than a movie star with his volume knob stuck at 11.

Newer viewers might also be struck by an underworld without drug deals or prostitution. Not a single civilian dies because of organised crime. No lives are wrecked by gambling, no businesses struggle to keep up payments to hoods running protection rackets. No one is a victim of mob theft or fraud schemes. The only police officer who appears to have a decent speaking role is a bent copper.

Even Vito Corleone, played by Marlon Brando, is a Mafia don out of a John Lewis ad. He’s a family man who dies while out playing with his grandson in the garden, he refuses to sell narcotics, and the film never challenges his excuse that the mob was his only way out of a New York ghetto.

No wonder the wiseguys in mob series The Sopranos adored The Godfather and constantly refer to it. Coppola’s film gives mobsters a cachet and glamour that is completely absent from their own lives. Under The Godfather, squalid lives become as weighty as Shakespeare and as juicy as one of Vito’s garden tomatoes.

But here’s a trivia question: what is the name of Vito’s wife? She flits through the movie as an irrelevant shadow, an old-style Sicilian grandmother who appears beside her husband in wedding pictures but never sets foot in his Rembrandt-tinted study.

Women barely exist in The Godfather. Sonny uses and abandons them, ignoring and humiliating his wife. Don Corleone’s daughter Connie (Talia Shire) is so excluded that her husband is not allowed into the family business, and when Carlo is killed, Michael lies about the death to his sister.

Apollonia (Simonetta Stefanelli), Michael’s first wife, speaks no English and within 15 minutes she has been killed by a bomb that is meant for him. Kay (Diane Keaton), Michael’s second wife, has the door firmly shut on her, so the guys can talk in private.

No wonder Luca Brasi, one of Corleone’s enforcers, plans to greet the Don at his daughter’s wedding with the words, “May their first child be a masculine child.”

It reminds me of a scene in the 1998 romcom, You’ve Got Mail, where Meg Ryan suggests that women cannot understand why men are obsessed with The Godfather, and Tom Hanks explains that men look to the movie for the answers to any important life questions they might have.

For instance: packing for a holiday? “Leave the gun; take the cannoli.”

It’s a fun idea, but I can’t agree that The Godfather is just a guy thing. Lots of women love The Godfather too, although I slightly prefer the more ambitious and unwieldy Part II.

Like skirt lengths and exchange rates, The Godfather reflected the state of the world at the time – in particular America in the ’70s, when it was engulfed by the chaos of Vietnam, racism, Watergate and the shockwaves created by the ‘60s counterculture.

The Godfather movies are about the implacable rule of one man who wants to preserve his family and bring order to his business, and the United States.

If that means bumping off a beloved brother, or any other unspeakable act, well that’s a price worth paying. Or at least according to The Godfather’s startling endorsement of corrupt, repressive power.

No other picture, before or since, has celebrated power like The Godfather.

If you root for anyone in this film, it’s for control freak Michael Corleone and his chilly authority; even Coppola was surprised and disappointed that fans applauded Michael at the end of the first film. After all, he was supposed to be the villain, not the hero.

Maybe the new Don Corleone himself had the explanation: “It’s not personal, Sonny. It’s strictly business.”

A neighbour threw a blanket full of guns into the apartment

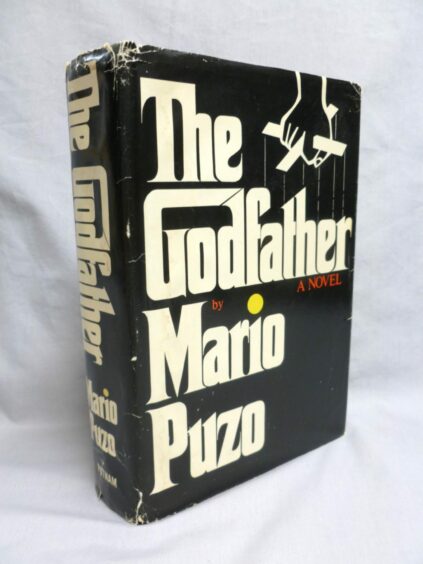

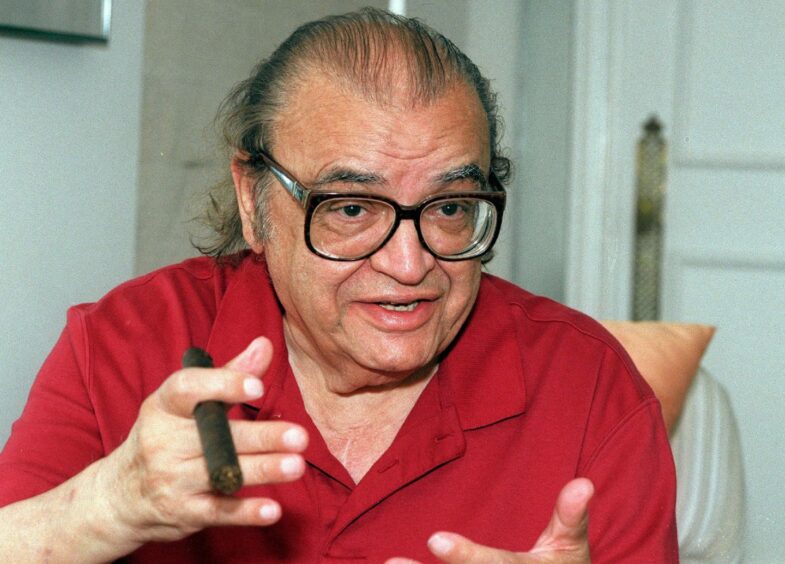

In Leave the Gun, Take The Cannoli: The Epic Story Of The Making Of The Godfather, celebrating the 50th anniversary of the movie’s release, author Mark Seal reveals how Mario Puzo, author of The Godfather, which would become one of the world’s favourite movies, revealed a most unlikely inspiration for mob boss Don Vito Corleone, unforgettably played by Marlon Brando, as he grew up in New York’s Hell’s Kitchen.

The toughest, most formidable person in young Mario Puzo’s life was his mother. Maria was known to brandish a policeman’s club with which she threatened to discipline her rowdy brood.

No one seemed to know where she got if from, though few doubted she might have filched it from a sleeping cop. Once, when she saw Puzo’s brother skipping work and driving around in his beat-up Ford with some neighbourhood girls, Mama Puzo picked up a cobblestone from the street and “brought the boulder down on the nearest fender of the tin lizzie, demolishing it”.

Puzo used Maria as the basis for the matriarch Lucia Santa in his 1965 autobiographical novel, The Fortunate Pilgrim. In one scene, Lucia rebukes her son for not doing his share of chores and disappearing from the house, the policeman’s club that Maria wielded replaced by a rolling pin. “By Jesus Christ, I’ll make you visible,” Lucia Santa threatens. “I’ll make you so black and blue that if you were the Holy Ghost you could not vanish. Now, eat. After, wash the dishes, clean the table, and sweep the floor.”

Puzo said that without his mother, he never could have created Don Corleone, much of whose voice and language came straight from Maria. “Whenever the Godfather opened his mouth, in my own mind I heard the voice of my mother,” Puzo wrote in the preface to the 1996 reissue of his novel. “I heard her wisdom, her ruthlessness, and her unconquerable love for her family and for life itself, qualities not valued in women at the time.”

She even provided him with some of the tale’s grislier material. “Many parts are true stories my mother told me,” Puzo told Life magazine.

“The man holding his hat to catch the blood from his cut throat, for one.”

The seeds of The Godfather were planted in an experience from Puzo’s childhood. One night the family was startled by a loud noise. “A neighbour across the tenement air shaft threw a blanket full of guns into the apartment and asked my mother to hold them for him, police were knocking on his door,” Puzo would write in a 1970 article entitled How The Mafia Makes Friends.

“My mother did so (though like most Italian mothers she went into hysterics when my older brother got so much as a speeding ticket. The next day the neighbour knocked on the Puzos’ door.

“‘You got my stuff for me?’ he asked. The neighbour who owned the guns became ‘protector’ of the Puzo family. He ‘reasoned’ with the landlord who tried to throw us out because we kept a dog.

“Then he said, ‘You want a nice rug?’ My mother says, ‘Sure.’ He says, ‘Send your son with me.’

“My brother was like 12 or 14 years old. The guy takes him to the house, they start rolling up this very expensive rug. All of a sudden there’s a knock at the door. The guy peeks out the window and draws a gun. My brother realizes it’s not the guy’s house and it’s not the guy’s rug.”

The connection continued to pay off. “This kindly neighbour saw to it that free coal was delivered to our house and that we received not one, but two free Thanksgiving baskets from the local political club,” wrote Puzo. “So the children in my family called him ‘Godfather’ in the same sense American kids in country towns call an elderly neighbour ‘uncle.’”

It was the first time Puzo heard the term that would shape his destiny. “He was a ‘Mafia’ man,” he wrote. “Our neighbour a generous man, and we never dreamed that he was a man who could commit murder for a price.”

Leave the Gun, Take The Cannoli: The Epic Story Of The Making Of The Godfather by Mark Seal, Simon & Schuster, £20

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe